East Meets West:

Indian Classical Music and Jazz

May 3, 2021 | by Rusty Aceves

Miles From India album cover detail

We look forwart to this week's Fridays at Five streaming concert featuring Miles From India, an incredible East-meets-West take on the music of Miles Davis. Here's a look back at how the Indian Classical Music tradition has intertwined with jazz throughout the 20th century and into the new millennium.

Despite the geographical distance and a chronological separation spanning many centuries, American jazz and South Asian classical music developed along similar pathways, evolving from the intertwining of sacred and secular traditions while valuing improvisation and the integration of sophisticated rhythmic concepts. So it was only right that ancient forms originating with Udgatar priests in 1500 BC and the African-American musical inventions of the early 20th century would eventually meet and build upon their common ground.

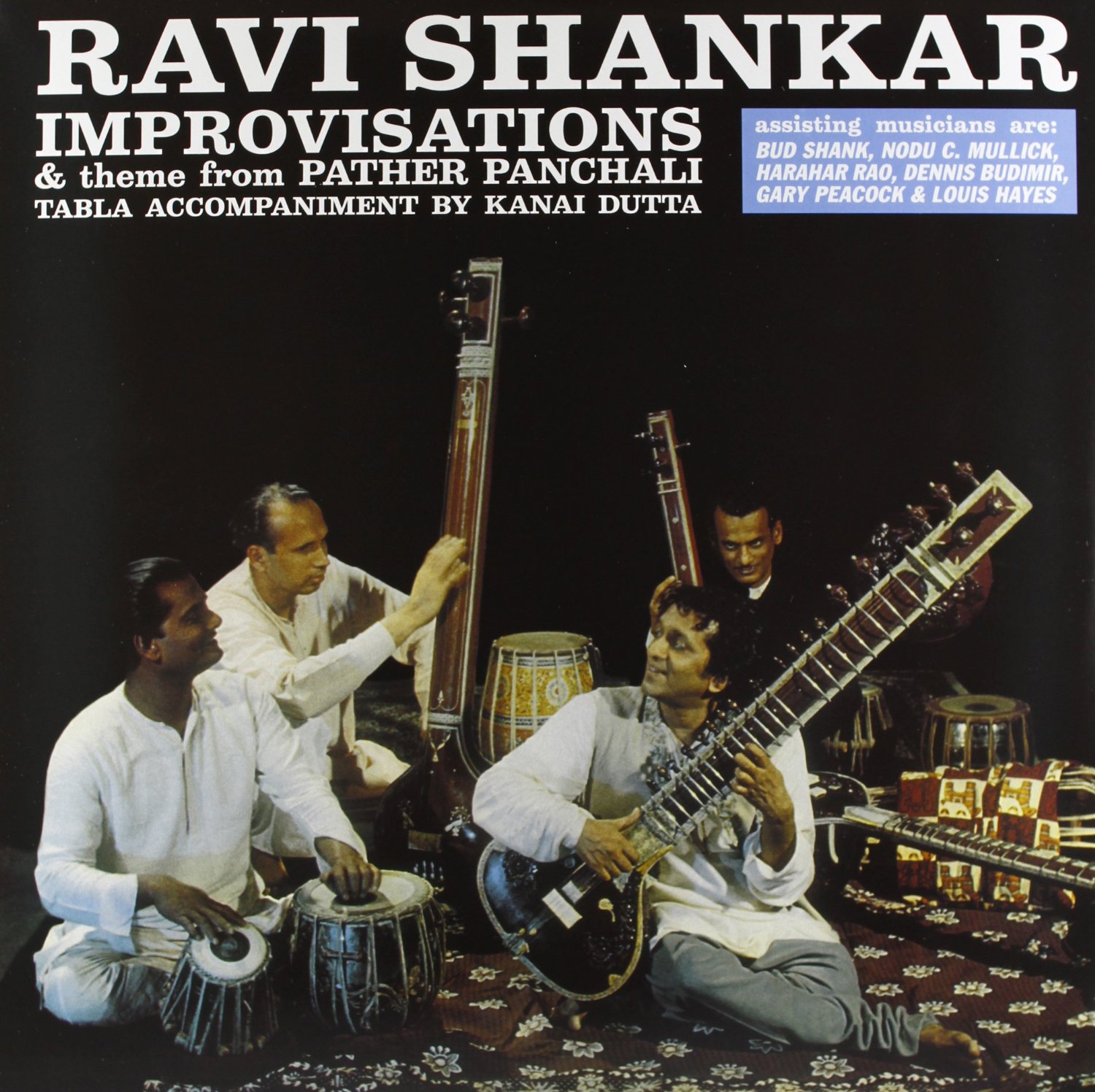

The jazz world’s first serious embracing of Asian music began in the 1950s, focused not on India, but with the Middle East and the exotic sounds of the Fertile Crescent and North Africa. Albums including wind master Yusef Lateef’s Jazz Mood (1957), Prayer to the East (1957) and Eastern Sounds (1961) along with bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s Jazz Sahara(1958) and East Meets West (1960) were among the first notable records to document the cultural blend. But the first major session to integrate jazz musicians with South Asian music was sitar legend Ravi Shankar’s Improvisations (1962), featuring flutists Paul Horn and Bud Shank, bassist Gary Peacock, and drummer Louis Hayes, along with a number of Hindustani backing musicians. Within the course of Shankar's monumental career, this recording was just one facet among countless others, but it quietly pioneered a cultural partnership that remains a rewarding meeting place for musical exploration.

The development of modal jazz – a compositional and improvisatory approach popularized by Miles Davis and John Coltrane and based upon the use of scales rather than standard chord progressions as harmonic framework – paralleled the increased visibility of Indian music in the west, and Coltrane in particular was heavily influenced by the flexibility he found within Eastern concepts. One of his most enduring pieces, the modal re-imagining of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things” from the 1961 Atlantic album of the same name, shows an unmistakable Eastern inspiration. His 1965 session Om (released in 1968) is named after the sacred Hindu syllable for the infinite and contains chanting from the Hindu Bhagavad Gita. Coltrane befriended Ravi Shankar in the late 60s, naming his son Ravi in honor of the sitarist, and Coltrane’s widow, pianist/harpist Alice Coltrane, heavily featured Indian musicians and concepts in her own music. She titled her 1970 album Journey in Satchidananda in honor of guru Satchidananda Saraswati, of whom Coltrane was a devoted follower.

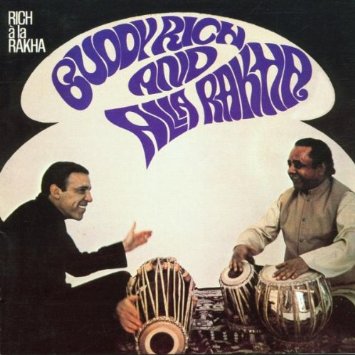

After Shankar appeared at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, his profile and that of Indian classical music exploded into the American popular consciousness. His tabla drummer of choice, Alla Rakha, also participated in the cross-pollination of jazz and South Asian music, recording a seemingly unlikely duet album with jazz drumming giant Buddy Rich, 1968’s Rich à la Rakha, with the assistance of Shankar and Paul Horn. The pioneering Rakha was widely considered the instrument’s greatest virtuoso, and his eldest son Zakir Hussain has in many ways eclipsed his father’s accomplishments, pushing the tabla’s possibilities to its limits and engaging a wide array of musicians not only from jazz and pop, but also from Latin America, Africa, and the Celtic tradition.

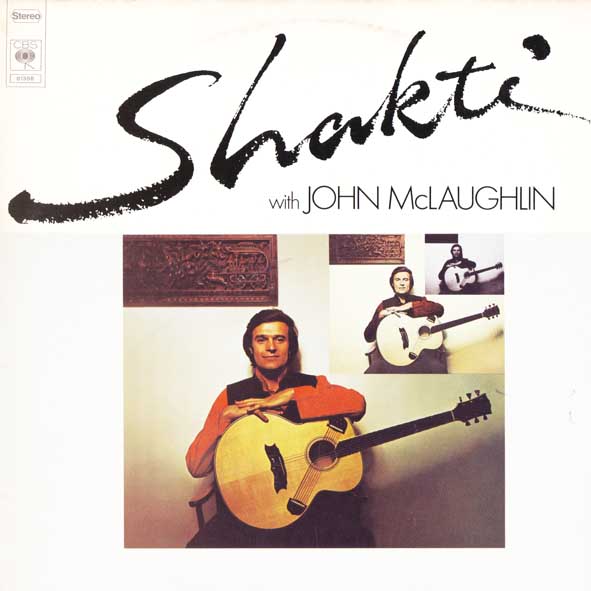

Hussain’s career was firmly established by the early 1970s on recordings by the Grateful Dead’s Mickey Hart and ex-Beatle George Harrison, and by mid-decade he had made foundational contributions to two of the greatest Indo-jazz fusion records of all time, Shakti (1976) from British jazz guitarist John McLaughlin and Karuna Supreme (1975) featuring saxophonist John Handy and sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan. Shakti in particular stands as a high water mark of East-meets-West collaboration, a live document of the 1975 performance at Long Island’s Southampton College with Hussain, violinist L. Shankar, and percussionists Ramnad Raghavan and T.H. Vinayakaram that, despite being entirely acoustic, displays as much fiery interplay and bewilderingly telepathic ensemble playing as McLaughlin’s electrified 1970s fusion juggernaut, the Mahavishnu Orchestra.

Originating from McLaughlin’s experiences while studying the Indian veena at the University of Connecticut in the 1971, Shakti has proven to be a richly rewarding musical entity, and has continued to perform and record in varying lineups into the 21st century. Since the flashpoint in the early 70s and continuing to the present day, Hussain has remained the primary motivator in engaging with the jazz world, recording with saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and George Brooks as well as guitarist Pat Martino and intriguingly, banjo non-conformist Béla Fleck. The tabla genius’ work with NEA Jazz Master Charles Lloyd and drummer Eric Harland in the trio Sangam has easily been some of the most stimulating world-fusion music produced in the last 40 years. Other notable musicians, including Bengali-born tabla player Badal Roy and sitarist Ashwin Batish, also moved widely within the jazz world. Roy appeared on Miles Davis' electrified releases On The Corner (1972), Big Fun (1974) and Get Up With It (1974), as well as Pharoah Sanders' Wisdom Through Music (1972) and recordings with saxophonist David Liebman, organist Lonnie Liston Smith and iconoclastic saxophone icon Ornette Coleman, who regularly employed Roy as part of his electro-acoustic Prime Time band.

As with most cross-cultural mingling, the intersection of Western and Eastern music has freed artists inspired by the wealth of global influences to explore beyond the musical traditions of their heritages. A student of Ravi Shankar, the late American sitarist and tabla player Collin Walcott performed on Davis’ 1972 fusion album On The Corner and made a major impact with his late 70s albums for ECM Records, as a member of the revered world-jazz ensemble Oregon, and as part of the global trio Codona with jazz trumpeter Don Cherry and Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos. Hungarian-born tabla player Péter Szalai was a student of Alla Rakha and performs mainly in traditional Indian classical contexts, saxophonist Kadri Gopalnath pioneered the use of the instrument in Carnatic music in the 1980s, and multi-percussion virtuoso Trilok Gurtu blends Eastern and Western concepts into his own singular approach that seamlessly marries traditional tabla playing with the American drum set. Saxophonist George Brooks has worked extensively to marry Carnatic music and jazz, recording and performing with Hussain, American drummer Steve Smith, guitarist Fareed Haque, bassist Kai Eckhardt and guitarist Prasanna in the groups Summit and Raga Bop Trio.

A number of young Indian-American musicians including pianist Vijay Iyer, saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa, drummer Sameer Gupta, and Pakistani-American guitarist Rez Abassi have blurred cultural lines still further, and increasingly, Indian-born artists have devoted themselves to the intersection of jazz and Indian music. Guitarist Amit Chatterjee was a member of keyboardist, composer and Weather Report founder Joe Zawinul’s working band for over a decade, and has lent his searing guitar style to work with saxophonist David Liebman and pianist Michael Wolff. Pianist and composer Louiz Banks performed with John McLaughlin’s Indo-Jazz group Floating Point and contributed to producer Bob Belden’s expansive Miles From India project with a selection of Indian classical and jazz artists including Badal Roy. Mumbai-born vocalist Shankar Mahadevan is a renowned playback singer for Indian films, and worked with John McLaughlin and Zakir Hussain’s Shakti reunion, Remember Shakti.

Today’s musicians and audiences live in a time when global influences and cross-pollination are an integral part of the creative fabric of modern music. With so much of the world obsessed with borders and isolation, these artists remind us that great music has always been a melting pot, an art form pointing to an idealized future in which the definitions and boundaries that separate us gradually cease to exist.

Originally posted on October 1, 2015