2020 NEA JAZZ MASTERS:

A Q&A with Roscoe Mitchell

August 17, 2020 | by Richard Scheinin

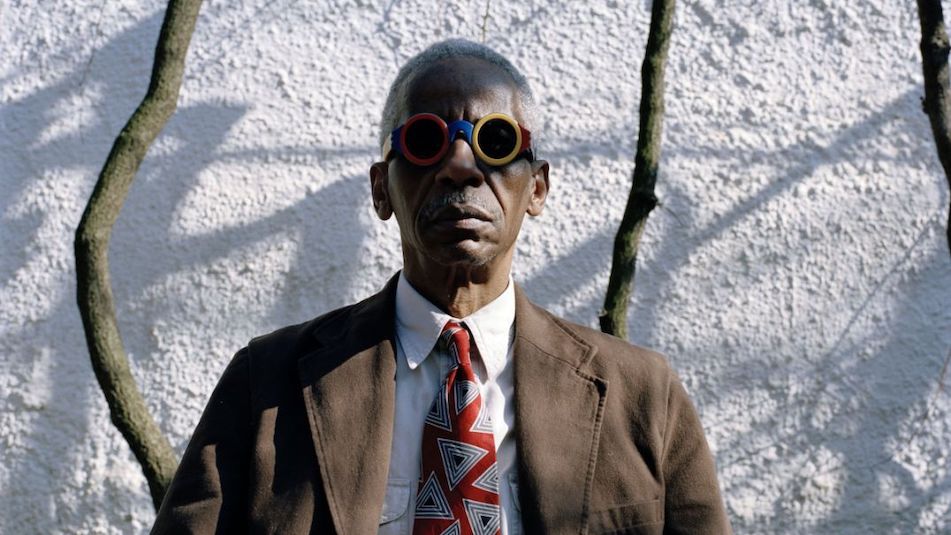

Roscoe Mitchell

Continuing a series of Q&A posts, SFJAZZ Staff Writer Richard Scheinin speaks (below) to Roscoe Mitchell, the legendary saxophonist, composer and 2020 NEA Jazz Master. In advance of the NEA Jazz Masters Online Tribute Concert on Aug. 20, Scheinin already has posted conversations with 2020 Jazz Masters Reggie Workman and Dorthaan Kirk. In the next few days, he will post a Q&A with drummer Terri Lyne Carrington, Music Director of the online tribute concert, hosted by SFJAZZ.

No one gets inside a note like Roscoe Mitchell; picking up his saxophone, he can make a room shake. Or he can sculpt the silence between the notes. He brings nuance to every millisecond of sound. Roscoe Mitchell delights in sound. And in doing so, he teaches us what jazz is about: curiosity, imagination, and finding a personal voice.

When he picks up the phone at his home in Fitchburg, Wisconsin, Mitchell—who joins Reggie Workman, Dorthaan Kirk and Bobby McFerrin in the 2020 class of NEA Jazz Masters — speaks about his life and career with a youthful, almost eruptive energy. He delights in discussing the details of process—the interconnections between improvisation and composition. He brings the same energy to descriptions of his boyhood and early career: seeing Duke Ellington perform in a movie theater in his Chicago neighborhood; randomly meeting saxophonist Albert Ayler while playing in a U.S. Army band in Europe; and, later, sitting in with John Coltrane’s group and experiencing pure sound.

Of course, he spoke at length about the early 1960s, when he came under the wing of pianist-composer Muhal Richard Abrams, whose Experimental Band was a training ground for Chicago musicians. Mitchell began to compose, and he united with a powerful community of open-eared players: Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill and Joseph Jarman, among others. This was the beginning of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, the AACM. It established Chicago’s place in the jazz vanguard, with Mitchell as one of its leaders.

The Art Ensemble of Chicago

(L-R: Joseph Jarman, Famoudou Don Moye, Lester Bowie, Malachi Favors, Roscoe Mitchell)

In the late ‘60s, he co-founded the Art Ensemble of Chicago: A groundbreaking band of the post-Coltrane jazz revolution, its performances were astonishing spectacles, sonically and visually. More than half a century later—with the Art Ensemble still performing in a whole new iteration—Mitchell continues to explore uncharted waters. He is always looking for new modes of expression, whether improvising with saxophones, bells and bicycle horns or composing for symphony orchestras and electronics.

One of the key conceptualists in jazz and modern music, Mitchell says, “It would take more than one lifetime for me to learn everything I would like to know about music.”

Q: You recently said that you’re more excited about music now than ever before. You’re 80 years old—how do you do it?

A: I never thought that I would ever end—it takes a long time to be what I’m trying to be! You know, a few years ago, when I was teaching out at Mills College (in Oakland, CA), I would be looking at my students’ portfolios and all the things they were trying to do, and I thought, “Wait a minute. I’m in the wrong business. I need to be a student!” And right now, I seem to have more ideas than I’ve ever had and I’m really enjoying having the time to really learn the things I’m trying to learn.

Q: Staying home during the pandemic is helping you focus on projects?

A: Yes, having this time right now to explore things and not feel rushed—I’m totally stoked about this. Right now, I’m working here with my wife, who’s a videographer, and we’re doing videos. You know everybody’s trying to reinvent what’s going on. You’ve got the whole streaming thing. And because all the festivals are canceled, people are asking me to send videos instead. For instance, the Bang on a Can festival asked me to do a video, and when I first started on that project, I thought, “Oh no, wait a minute! Maybe I better find a different profession.” I knew I was trying to get to something, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on it. But I stuck it out; all of a sudden I had the time to pursue it—to think of an idea and see it through.

This is an exciting period and whoever doesn’t know that, doesn’t know much. You got a ticket to ride or you don’t.

Q: Were you a curious child?

A: I was totally curious as a child. I came up in an environment where people around me were always inventing things. My Uncle Arthur, he made a lot of our toys for us, carved out of wood. And my Uncle Charles, he made something like a comic book where he used pen and ink and crayon—and he had made these books showing me and my sisters and our friends as people from outer space.

Q: You were characters in the comic books?

A: That’s it. And my dad knew something about everything; I don’t know how he was that brilliant. But whatever he was doing, I was doing. And he taught me everything, man. If he was working in a garage on cars, I’d be going with him. See, back then, it wasn’t, “Oh, you’re only five. You can’t do this.”

It was about apprenticeships. All you had to do was prove that you were interested in what they were doing, and so they would take you in. We didn’t have to go out of our neighborhood to learn something. Everybody had a garden, so you learned to garden. When it snowed in Chicago, people would put out buckets to catch the snow and make ice cream. Totally different. You had to make up your own things. And you didn’t have to leave the neighborhood to make a living. I’d like to see some of that come back, in a way.

I had great influences growing up. We didn’t have to leave the neighborhood to find our heroes.

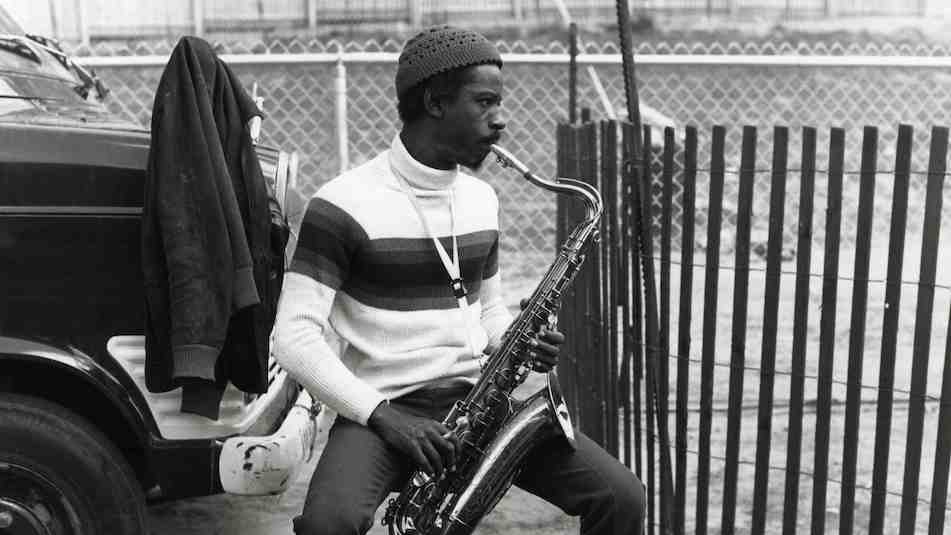

Roscoe Mitchell, 1972

Q: What about musically? How did you get started?

A: My brother Norman had this collection of 78s. He had everything. We called them “the pillars” back then: Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Billie Holiday, Billy Taylor—all of those “pillars.” He would sit me down and have me listen to them.

Q: I’ve read interviews where you talk about the neighborhood movie houses—and how people like Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald would perform there. You saw them as a kid?

A: Absolutely. We’d go to the matinees at the Regal—there was a lot of live music. That was just the way it would go. You’d go and see the movie and then there’d be an intermission and the live bands would play. And then they’d finish and you’d go back to the movie.

Q: When did you get started as an instrumentalist?

A: I consider myself a late starter. Kids today, they start very early. I actually started playing clarinet in my first year in high school or something like that. People back then, they always would say, “If you want to play the saxophone, you should start on the clarinet.”

Q: How did you get started on saxophone?

A: I was in high school and the student that was playing the baritone saxophone graduated. And Mr. Colbert, the bandmaster, asked me if I wanted to play the baritone, and I said, “Yes.” So that actually was the first saxophone I started to play—the baritone. I didn’t get my first alto saxophone until I’d gotten into the Army. I was in Luxembourg, and I got a brand new alto. That’s when I first owned my own alto saxophone.

Q: People who heard Ornette Coleman in the mid-‘50s often say he sounded just like Charlie Parker. What did you sound like early in your career?

A: I didn’t sound like nothing.

Rubin Cooper—this great saxophonist from Chicago—was in the Army the same time I was, and he took me under his wing. And he was teaching me scales, the basics, because I guess he saw something in me. And that’s what I always remember—people who took time to help me out when I needed it. And that’s why if somebody asks me to help him with something today, I have to do that.

So I wasn’t sounding like too much. And I remember asking Rubin, “Man, one of these times, do you think I’ll get lucky and sound like something?” And he said, “No, if that happens, that’s the time to start working.” There were some great musicians in the Army. I was lucky to be in the Army at that time.

Q: Tell me more about your Army years.

A: I’d had a friend Romero in the Army who introduced me to Ornette’s records, and I listened, but I didn’t really understand. But our band from Heidlelberg, we would go to Berlin and we would get with the band in Berlin. And then the Army band from Orleans, France, would come—and Albert Ayler was in that band. That’s when I heard Albert Ayler; I’m just trying to show you the connections. I didn’t know what he was doing. But I knew he had an enormous sound on the instrument, and that’s always what drew me to different saxophonists—the different sounds they had.

And then when I went back to Chicago, the thing that really got me was Coltrane—that record with “Out of This World” and “Inch Worm” and all of these pieces. (The album was Coltrane, recorded in 1962.) It had never occurred to me that you could use a modal concept to create something like that in music.

John Coltrane: "Out of This World"

Q: OK, so you’re out of the Army and you’re back in Chicago—and this is when you come under the wing of Muhal Richard Abrams. It’s the beginning of the AACM era.

A: Right. And I would say the people of Chicago were much further ahead than me. That’s when I went down to the C & C Lounge to meet Muhal, and the Experimental Band was meeting there every week, rehearsing. And they greeted me with open arms and I started to go over to Muhal’s house and he started teaching me.

Yeah, I’d d say I was a bit behind.

So that’s why I always say if somebody doesn’t understand what I’m doing, I’m not bothered by that—because as a musician it took me a while to understand what I’m doing musically. And at Mills College an older gentleman came up to me one time and said, “I came here determined not to like you, and you won me over.” And now when I go to Chicago and I see people in the audience that have been with me all these years, that is encouraging and inspiring to me. So I’m nowhere near finished with what I’m doing. I’m not the kind of guy who wants to play the oldies but goodies. Most people come up to me after a concert and they don’t say, “I like it,” they say, “I need it.”

Q: You mentioned Coltrane a minute ago. You sat in with him in Chicago?

A: Right, at the Plugged Nickel with Jack DeJohnette on drums—you know, Jack and I had a band before he left Chicago to go to New York. So that night it was Alice (Coltrane), Jimmy Garrison, and Rashied Ali, and Jack—and Pharoah Sanders was there with Coltrane, too.

Jack asked Coltrane to let me sit in, and then I always had my horn in the trunk of my car. So I went and got it and sat in with them, and when the first set was over, I started to pack up, and Coltrane said, “No, come on back. I like what you’re doing.” And we played past one in the morning; the owner was ready to close up. And Roy Haynes came by that night and sat in. And Pharoah was sounding amazing; he had this whole bag full of mouthpieces and he’d reach into that bag and grab a new mouthpiece and he became pure sound. They called “Naima,” and I was able to play something and that was a highlight of my life.

Q: It’s interesting to hear you talk about your connections to Coltrane. Jazz histories often describe the AACM as happening independently or even in opposition to what Coltrane was doing.

A: Everything everybody writes is not accurate. I would say the difference back then between New York and Chicago was that in Chicago people got together and rehearsed. It’s hard to go to New York and have your own band; you normally ended up in somebody else’s band. They had their own take on the music and the Chicago musicians had their own take. That’s not a bad thing, because it all adds up to be what it is as a whole.

Of course, there’s a connection. Look at all the great work that all the musicians have done throughout the years. When I was in Paris, I met so many musicians. (Saxophonist) Frank Wright’s group had the drummer Muhammad Ali; whenever he hit a cymbal, it was a world of sound. You heard that and you tucked that away. So there’s something to be learned from everybody. Once you stop being a student, you’re dead.

Art Ensemble of Chicago - Live in Warsaw, 1982

Q: Did you feel like a student with the Art Ensemble?

A: Sure. I’ve been lucky in my career to be in the right place at the right time. The Art Ensemble was like five individual thinkers, but we rehearsed a lot too. Going to our rehearsals was like going to school, always learning something—and that carried over to the AACM, too, in a way. When you go to the rehearsals—and eventually we moved into the Abraham Lincoln Center down there on East Oakwood in Chicago—it’s like going to school and we had our own school for young aspiring musicians. And when Muhal was alive, whenever we got together it was like we picked up from wherever we left off, because it’s an ongoing thing. And I think it’s not a bad idea to have long-lasting musical relationships in music. It takes that kind of a work ethic.

I’ll stick with something for a long time, man. If you were to say to me, “Hey, man I’ve got this ensemble and I need this new variation of `Nonaah’ in a couple of days,” I could do that for you. It’s a whole system.

Q: You’ve got this long history with your piece “Nonaah.” Maybe you can talk about that. Because what you’ve done with “Nonaah” over the last 40 or 50 years is kind of symbolic of your whole musical approach.

A: It started when Anthony Braxton was going to play at the Willisau Festival (in Switzerland) in the ‘70s, but he couldn’t make it. So I replaced him and I played a solo saxophone piece, and that was “Nonaah.” It’s a piece that has these wide leaps between the high and low melody, and when people hear that, it can almost sound like more than one instrument is playing. So it started out as a solo piece and I used that to generate other versions; I’ve done several versions. It went up to a version for chamber orchestra; I used the harp to enhance the strings, and I put in a tubular bell with the percussion. But then when I was invited by Ilan Volkov, the conductor, to work in Glascow, Scotland, I took the piece into full orchestra. I added the full percussion and the brass, and at that point I realized that “here’s the piece that started for solo saxophone and now I’m reinventing the piece for full orchestra.”

And for me it was the end of a journey in a way. And a lot of times with my work, I’ll stay with something for a really long time because I’m trying to get under the surface. That’s another thing I’m enjoying about this period, with this pandemic—I can play the same note for a week if I want to. I have the time to do it.

Art Ensemble of Chicago and Muhal Richard Abrams: "Nonaah"

Q: And now you’re performing “Nonaah” again. You’re recording it with a quartet—alto saxophone, trumpet, bass and percussion—for the NEA Tribute Concert.

A: There’s no lack of things to do. Every time I do a new version of a piece, it becomes a brand new piece. Sometimes they have different improvisers, so it keeps changing. That’s how one thing leads to the next. Once I have the transcription of the original improvisation, I can mold it and shape it any way I want to create another piece.

Q: Who introduced you to the idea that improvisation and composition are related processes?

A: Muhal introduced me to that idea a long time ago: “Hey, man, go and write down some of the melodies you’re improvising on your horn.” So that’s what it is—it’s an extension. In order to be a great improviser, you have to know how composition works, otherwise you’re just skimming around on the surface. So with my students, I always tell them, “You get an idea, you exhaust the idea.”

I always advise my students to do solo concerts; you have to know what it’s like to be the only person out there. And the opposite of that is to be able to shift it over to playing in a large ensemble, and that’s when things become on another level. So you’re working from both ends of the spectrum and that kind of helps with what needs to go on in the middle.

And I did a lot of workshops, and what I started to notice was that inexperienced improvisers tend to make the same mistakes. A lot of times, they’re following what the other people are doing: “I’m waiting to see what you’re going to do.” But when I do that, I’m already behind. So I tell them, “Leave some silences in the music.” Silence is perfect. You have to study that. You have to go somewhere where it’s really quiet and see how intense it is. So it’s on you that when you come in, it has to be on that level. If it’s not, you’re going to be exposed.

Q: So you tell your students, “Don’t follow. Listen.”

A: It takes concentration. If somebody’s playing something that you like, don’t just jump in there and do it—you’ll only interrupt their thought processes. If you hear something you like, store that idea away and bring it back in another way later on. That’s what I do; I can just reach into my memory and bring in a variation of some idea you presented earlier. And then you’ve created another element, and all of a sudden we have counterpoint.

All of the great composers, like Charlie Parker, man—his solos are compositions. But that took some hard work. He worked 15 hours a day on what he was doing for I don’t know how long. There’s no free lunch. You’ve got to do the work, and then maybe one night you can go out there and you can’t do no wrong. But that’s not often.

There’s no end to this work.

Roscoe Mitchell: "Bells for the South Side"

The 2020 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert will take place on Thursday, August 20th from 5-6PM PT. It can be streamed without charge at SFJAZZ.org and arts.gov.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.