Cécile McLorin Salvant

Ogresse

July 21, 2020 | by Richard Scheinin

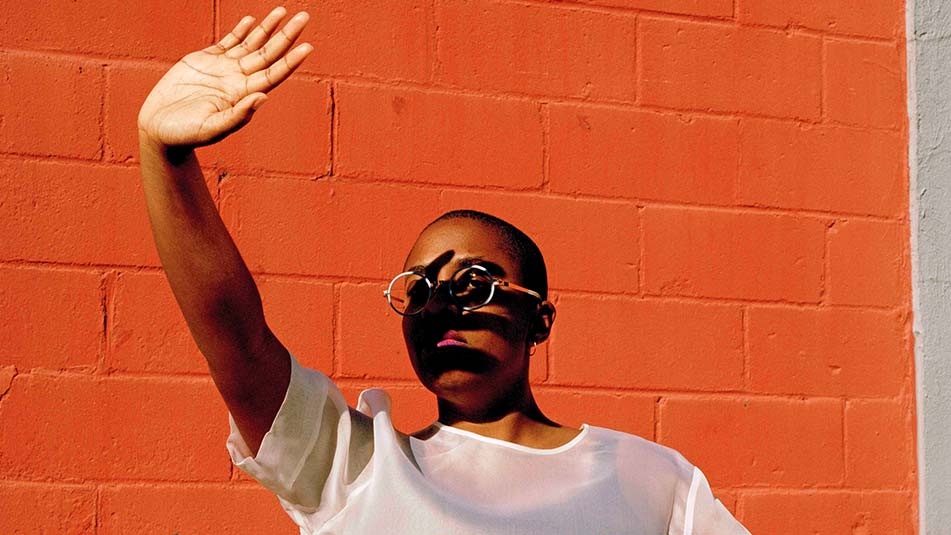

Cécile McLorin Salvant in Ogresse

This week's Fridays at Five streaming concert takes us back to opening week of our 2018-19 Season, featuring GRAMMY-winning singer Cécile McLorin Salvant and pianist Sullivan Fortner. With Fridays at Five, we are able to still support artists through the virtual Tip Jar, and proceeds from this week's Tip Jar will be split 50/50 with Cécile and Sullivan.

In February, SFJAZZ staff writer Richard Scheinin previewed Cécile's 2019-20 Season performance of her song cycle Ogresse—the first SFJAZZ show canceled by the COVID-19 pandemic. The decision to cancel the show came when Cécile and her ensemble were rehearsing on stage at Oakland's Paramount Theatre, and a scaled down version was instead performed that evening at the home of author and Civil Rights icon Angela Davis (story here). We look back at Richard's preview.

Cécile McLorin Salvant has an effective elevator pitch for Ogresse, her wickedly delicious song cycle about a human-eating monster in the woods. The story, she says, goes like this: “She falls in love! She eats the guy! She dies!”

Salvant — who is 30 and a three-time GRAMMY award winner — has adored fairy tales and myths since she was small. But her reputation, until lately, has rested on her gift for interpreting standard songs. Tapping into a lineage — Bessie Smith, Betty Carter, Abbey Lincoln — she’s comfortable with the blues. She understands irony: On WomanChild, her breakout album from 2013, she shocked some listeners by including a dated number from the 1930s, “You Bring Out the Savage in Me,” yodeling like Tarzan in the chorus, letting her audience feel some discomfort over the song’s racial baggage — but embracing the melody, too. She is a singer who thinks like a stage actor or director (there’s always a subtext), daring her audience to stick with her as she establishes her vision. She does it again with Ogresse, her 85-minute, multi-media composition for which she also wrote and illustrated the libretto. (Copies are distributed to the audience after performances.) Accompanied by a 13-piece chamber orchestra — arranged by Darcy James Argue, who conducts — Salvant is taking it on a West Coast tour that includes a March 11 performance at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, presented by SFJAZZ.

Argue remembers that when Salvant first laid out the story for him — “this dark and poignant and compelling fairy tale that she had invented” — he responded in a word: “Amazing… and also, what it looks like here is you’re conspiring to alienate your whole fan base!” Salvant is taking a calculated risk with this piece, he believes. It is “a serious departure, especially for those who only know her as an interpreter of standards. But she is so much more than that. She is a great artist and illustrator. She embroidered her own robe for Ogresse. She plays the lute, and when we brought in a Baroque organ for the shows at Lincoln Center” — where the work was performed twice in September — “she busted out her Bach chops at soundcheck! She has such an incredibly diverse and complete set of talents that — how am I going to phrase this? I just feel like her audience so far has really only been able to access a small sliver of her total artistry — and that Ogresse brings to the fore that she is not only our generation’s greatest interpreter of standard songs, but is a wonderful songwriter and conceptualist and ‘Big C’ composer. Her ability to inhabit the character of a song is something that really comes to the fore with this project, and it’s because of that that her audience is willing to follow her to these dark places.”

Ogresse is the tale of a ravenous black monster in the forest. This lonely, lovesick monster-woman is a classic outcast, who also happens to be a cannibal — as the nearby townsfolk, including an opportunistic bounty hunter, soon find out. You can call it a jazz opera, though maybe, given its macabre subject matter, Ogresse is better described as Salvant’s Sweeney Todd. Like that musical by Stephen Sondheim, it manages to humanize the monstrous character it depicts. Gathering momentum across 17 songs, all sung by Salvant from shifting perspectives as she moves between four separate roles, Ogresse is at times cringe-worthy, but it is filled with humor, empathy and beauty, too. To hear her sing the role of the monster — at times weirdly detached, even as she kills, but then becoming love-struck, heart-broken and eventually howling with grief — is an experience.

Cécile McLorin Salvant in Ogresse

The libretto tells us that the Ogresse’s mouth is “the size of a planet” — all the better to eat you with, my dear. Likewise, the work reflects Salvant’s own ravenous musical tastes. Her through-composed score includes late-night ballads and swirling jazz waltzes; up-tempo “swingers” evoking the ‘50s Hi-Fi era; sprightly French chansons; Baroque laments that spell pure sorrow; and a batch of Appalachian two-step numbers. Those rustic tunes feature wild-card banjoist Brandon Seabrook, one of 13 members of L’Orchestre L’Ogresse, as the ensemble is known. Salvant — who has a French mother and a Haitian father — notes that the banjo has roots in West Africa and conveys “a traveling diaspora vibe, that quality I was looking for. Because this work for me is just all foundationally based in folk music and folk tales, so I wanted us to always come back to that folkloric sound.”

She connects Ogresse to her work of the past decade, to songs that “deal with identity and stereotypes and race and the ways we can surprise ourselves.” She brings all of that to her theater piece, which began percolating in her head about three years ago: “I felt that I wanted to touch on some kind of female monstrosities and female villains — mythical female villains,” she explains with a chuckle, speaking by phone from her home in New York. “I just loved how provocative the idea of a female monster was and how much it links to so much of my childhood. I remember my sister telling me all these crazy scary stories, and I remember being really fascinated by Ursula in The Little Mermaid.” She is referring to the wicked sea witch in the Disney film, which was adapted from a tale by Hans Christian Andersen. Ursula left her “feeling very terrified, but also very attracted.”

As the idea for the ghoulish song cycle took hold, she went into research mode: “I started looking up different fairy tales about female monsters, and I found, or just remembered, the concept of the ogress. And the ogress often is presented as the wife of the ogre, as a secondary character. And little by little, I just latched on to `Ogresse’ as the title” — she went for the French form of the word — “and became very possessive of it and thought it should be its own story. I remember I was in Paris and wrote it down on a little piece of paper, the whole plot right there.”

She falls in love. She eats the guy. She dies.

Vibraphonist Warren Wolf plays the first note of the piece. As instructed by the score, he runs the bow of a bass violin — slowly and gently — across the back of one of the bars of his vibraphone. The note (high G above middle C) rings out to eerie effect — a novel sound to Wolf who finds the score to be full of challenges. When he first was asked to perform the piece with Salvant, he assumed he would be an add-on to her standard trio or quartet, stepping out now and then to take a solo. “But it’s nothing like that,” says the vibraphonist. A one-time child prodigy, he grew up playing in orchestras and jazz combos. “I take a few solos on vibes and marimba, but I’d say 80 percent of the music on my end is written out. There are so many parts and notes to be followed — it’s not like a typical jazz concert. You feel like you’re in an orchestra. The last time I was involved with something like this as a section player was maybe in high school or when I was playing with the Baltimore Symphony during my mid-teen years. I’ve been on the road for 20 years and it’s a long time since I did anything remotely like this.”

Familiar to Bay Area audiences as a member of the SFJAZZ Collective, Wolf is struck by other aspects of Salvant’s song cycle: the score’s recurring connecting themes and the many unusual effects created by Argue through his orchestrations. After the Ogresse eats a girl from town named Lily (“How can there be skin so white/So white its diaphanous/It’s making me ravenous”), trombonist Josh Roseman switches to tuba and “goes up into the upper octaves, like he’s imitating the human voice,” Wolf says. While this is happening, Salvant sings — in French — a recipe for “chair fraîche de payson” (fresh flesh of peasant), which she adapted from a favorite recipe for beef bourguignon. Elsewhere in the score, the Ogresse wanders “outside in the forest, in the sun,” Wolf recounts, “and Darcy has created these interesting birdlike calls that are played on piccolo (by Alexa Tarantino) and oboe (by Tom Christensen).” Wolf is impressed: “The piece is filled with a lot of things that you typically wouldn’t hear, and the way Darcy’s got it, it all sounds good.”

Darcy James Argue

Argue (whose own 18-piece Secret Society big band performs at SFJAZZ on April 18) explains that he “tried to be almost invisible as an arranger, to approach Cécile’s music in terms of what does this song need, and what is this moment about? Because each song has to fit into a narrative, and the orchestration is part of how the story is told, and there’s a lot going on. Cécile is singing from the perspective of the narrator, and then she’s singing as Lily, the girl who gets eaten, and as the bounty hunter, who gets eaten by the Ogresse.” He stifles a laugh, then continues. The orchestration should help delineate each of the singer’s roles, he says. “But the other thing is, Cécile never sings it the same way twice. There are new emotional shadings of the characters that she’s constantly finding with each performance. That’s part of who she is as an artist. It’s not about making fixed choices with her. It’s more like each character’s journey is a little bit different every night.”

The chamber orchestra’s quirky instrumentation — it includes melodica and Baroque organ, each played by pianist Helen Sung — is the result of much back-and-forth between Argue and the composer. From the beginning, Salvant lobbied for banjo, oboe and strings, she says, and “we filled it out from there.” Together they recruited Seabrook, Wolf, cornetist Kirk Knuffke, bassist David Wong — the ensemble is filled with top-tier jazz players — as well as the Mivos String Quartet, a New York-based contemporary music outfit. Argue admires the way Mivos can “play all of this high modernist and new-complexity music with the thorniest extended techniques possible,” he says. But it also can turn around and “play swing rhythms really convincingly — and that’s not something you can ask of most string quartets.”

As Salvant and Argue assembled the orchestra, they decided to forego a trap drum kit. Instead, they brought in percussionist Samuel Torres to play bongos and cajón, congas and rainstick, shakers and thunder drum. Torres adds so many colors to the piece without overwhelming things, and Argue sounds relieved: “If I’m writing for string quartet, I don’t want all of their beautiful sound to be swallowed by a ride cymbal.”

Choosing to perform without a trap drummer turned out to be a deft move. It “pulls the piece out of a genre,” Salvant says — makes it harder, in other words, to stick Ogresse in a “jazz” box or a “Broadway” box or any other box.

What the piece is is a kind of summation of Salvant’s many lifelong interests: myth, musical theater, visual arts, cooking, French language and culture. After graduating high school in Miami, she attended conservatory in France and studied Baroque vocal technique. In fact, “Ogresse’s form and structure,” she explains, “is based on the form of two things that I love, one of which is French Baroque cantatas — their idea of embodying all these different characters, and it’s done with one singer and an orchestra.”

“The second thing is, I was listening to Jelly Roll Morton’s ‘Murder Ballad’” while getting to work on the song cycle, she says.

The “Murder Ballad” is a 30-minute blues suite, recorded by Morton at the Library of Congress in 1938. It’s a narrative about a woman who goes crazy when another woman seduces her man. She vows to teach the other woman a lesson, shoots her dead — between the eyes and between the thighs — and goes to prison, where she laments her own wasted life.

Morton, the seminal New Orleans pianist and composer, sings the tale from shifting perspectives. He’s the narrator. He’s the killer. “It’s incredible,” says Salvant, who sang “Murder Ballad” at Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2017. “I performed it to an audience that was quite stunned, because there’s so much profanity, and it really goes there – and I think people often have a very specific perspective of what jazz and blues is, and they’ve kind of whitewashed it and cleaned it up and made it sort of family-friendly. Not that it can’t be family-friendly, but the music is not something that you can pin down. It refuses to be pinned down. And for Jelly Roll to be singing in the ‘30s from the perspective of a woman – it’s such an example of a man demonstrating empathy, an incredible amount of empathy. It’s like he becomes this woman who’s going through all kinds of things and goes to jail, where she has her lesbian moment, even, and so much confronts her. Death confronts her. It has all these themes – feminist themes, themes of female solidarity and sex and murder and race.”

Cécile McLorin Salvant

When Salvant performed “Murder Ballad,” she recalls, “I was scared. But once I did it, I realized how much I wanted to work with longer story forms. Up to now, the pieces I’ve sung have been a song from a musical or a song from the popular music tradition. But I love the idea of building an arc and telling a story and getting to milk every bit of it myself.”

In creating Ogresse, she also considered the story of Sarah Baartman, a member of the Khoikhoi people in what is now South Africa. Abducted and exhibited in 19th-century freak shows in Europe — people were amused by her huge buttocks — she was derisively labeled the “Hottentot Venus.” Her exhibitors “would show her in salons, and people would come and look and laugh at her, and she became quite an attraction just because of her body and her form. It’s quite horrifying — your typical example of fetishism of the female body, of the black female body. So part of this is also an ode to her.”

And there was this other touchstone for Ogresse: “When I was 25, I went on Pinterest, because I love to go on Pinterest and Instagram to look at images. It’s a disease.”

One day, she was looking at examples of Haitian folk art and was struck by “this painting of a woman, this giant woman, naked in the middle of the canvas, and she is peeing, I guess, and her peeing becomes a stream filled with fish. And now it’s in my living room. I see it every day,” Salvant says, explaining that her mother tracked down the artist, bought the painting and gave it to her as a birthday gift. “And I really think this image has seeped into my life. She’s Mother Nature. She’s holding three candles, and there’s trees all around her.” The image represents a Haitian Vodou goddess, Erzulie Fréda Dahomey: “She’s like the spirit of love and flowers and all sorts of things. And I see her every day; I live with this image, and I really think that became Ogresse!”

Sometimes life really does become art.

Salvant — transfixed by The Little Mermaid since she was a child — now plans to turn Ogresse into an animated film. Already, she has hired an animator, Lia Bertels, with whom she is working on preliminary sketches. And in December, she and L’Orchestre L’Ogresse went into the studio and recorded the song cycle: “So that record is going to be the soundtrack to this 85-minute, feature-length animated movie we’re making. It’s still in its initial stages. We’re looking for funding. It could be years.”

Doubt it.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.

Originally posted February 19, 2020