2021 NEA JAZZ MASTERS:

A Q&A with TERRI LYNE CARRINGTON

March 31, 2021 | by Richard Scheinin

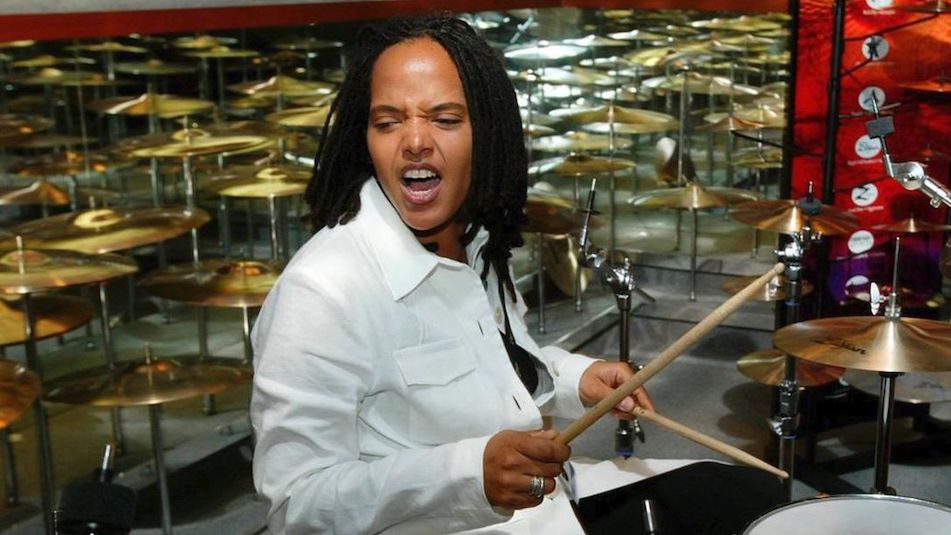

Terri Lyne Carrington

In the first in a series of Q&A posts, SFJAZZ Staff Writer Richard Scheinin speaks to Terri Lyne Carrington, acclaimed drummer and 2021 NEA Jazz Master. In the coming weeks, Scheinin will post conversations with the other members of this year’s class of NEA Jazz Masters: drummer Tootie Heath, saxophonist/composer Henry Threadgill, and radio deejay and historian Phil Schaap. He also will speak with saxophonist Miguel Zenón, Music Director of the NEA Jazz Masters Online Tribute Concert , a co-production with SFJAZZ, streaming on April 22.

In the course of her 40-year career, drummer Terri Lyne Carrington has played with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock… Stan Getz and Dizzy Gillespie… Al Jarreau and Esperanza Spalding… Lester Bowie and Woody Shaw. The list goes on. But she is not just a drummer. “Art documents your evolution,” she says. And Carrington keeps evolving; she is increasingly busy as a composer, educator, bandleader and producer.

Music is in her DNA.

Drummer Matt Carrington, her grandfather, played with Duke Ellington and Fats Waller. Saxophonist Sonny Carrington, her father, has been active on the Boston jazz scene since the 1960s. Around 1970, when Terri Lyne was five, Rahsaan Roland Kirk brought her onstage to shake a tambourine to “Volunteered Slavery,” one of his anthems. A year or two later, she recalls, “I started playing alto saxophone, and he let me sit in with him — just playing a riff, because I couldn’t really play much more. I was a kid. And when I was seven or eight, I started playing drums and that’s when I began to discover where my true talent and interest lay. Rahsaan let me play drums with him as well. He was so encouraging every time he came to town — and it probably helped that my dad knew him.”

She didn’t need too much help. When she was 10, Carrington got her first professional gig as a drummer, with trumpeter Clark Terry. Even before moving to New York in 1983, she was mentored by some of the most revered drummers, including Max Roach and Jack DeJohnette. In the years since, her artistic life has been one of consistent growth, identifying new challenges and breaking down walls. Carrington is the first — and so far the only — woman to win a GRAMMY award as a jazz instrumentalist. She won it in 2014 for Money Jungle: Provocative in Blue, her reinterpretation of Duke Ellington’s classic 1962 trio date with Charles Mingus and Max Roach. With Money Jungle, Ellington made a statement about the conflict between art and commerce. For Carrington, such statements are important; music can (and perhaps should) be about more than music. Over the last decade — going back to 2011’s The Mosaic Project, a collaboration with 20 musicians, all women — Carrington has released a string of albums that reflect on social themes. Last year’s Waiting Game, by her band Social Science, addresses Black Lives Matter, police brutality, homophobia, and gender equality.

At the Berklee College of Music in Boston, where she has been on faculty for 15 years, Carrington is the founder and artistic director of the Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice. Historically, jazz has been male dominated. But the Institute aspires to jazz without patriarchy, she explains, bringing young women and men into the fold, offering them mentorship, support, and professional access, with both gender justice and racial justice as guiding principles. “It’s not rocket science,” she says. “The idea is to take a serious look at what some of the problems are, and to do the best you can in addressing those things — to participate in making a difference.”

I phoned Carrington, 55, at her home in Boston to talk about her decades in the music — and the future she sees for herself and jazz.

Terri Lyne Carrington with the Wayne Shorter Quartet at SFJAZZ, April 2017

Q: Let’s talk about some of the musicians who’ve played a key role in your life and career. What can you tell me about Wayne Shorter?

A: Other than that he’s a genius? To be around and just pick up information from people like Wayne is important. They talk to you about how to be an artist, how to be an artist citizen, how to be a teacher. They teach you how to commit to something, to not stray or become distracted — to be mission oriented.

By observing somebody being their highest self, it inspires and encourages you to be your highest self. Wayne’s just one of the most amazing human beings I’ve ever been around. He definitely changed my life. Really, he’s just the greatest. Like Muhammad Ali’s the greatest? Wayne’s the greatest.

Q: Describe your bond with Cassandra Wilson.

A: Ever since I’ve known Cassandra, we can just go. For us, conversation is just like the music, where I feel like we’re actually playing together. The creativity and the conversation and the music all feel connected. The other person I feel that way with is Esperanza Spalding.

Cassandra is like a sister to me, and she is just an amazing musician. She’s figured out her individual sound and cultivated her own voice. She committed to what was in her head.

Q: What made Clark Terry such an important mentor?

A: He taught me a lot about the tradition of the music — and about life. When I was 18, he took me on my first tours, in Europe. I remember him talking me into buying this leather coat; it was the first time I ever spent that kind of money on a clothing item. He kind of gave me permission to do that, to blow a week’s salary and treat myself.

Clark really cared about young people and the future of the music. And he was practicing gender justice before it was fashionable — Wayne Shorter, too, and Billy Taylor. For me, those are the people who were all about gender equity, even though we weren’t talking about it in those terms.

Terri Lyne Carrington on stage with Dianne Reeves

Q: I know you go way back with Dianne Reeves.

A: She’s my oldest friend — since I was 10 years old. That’s a 45-year friendship! She’s somebody else that’s taught me a lot about commitment to your art. Whenever she opens her mouth, whether to sing or to talk, she’s giving you a hundred percent.

Letting people into your world, into your soul, into the deepest most precious parts of yourself — that’s what we try to do as musicians and artists, but it’s not always easy. And she’s really a master at sharing her authentic self, leaving it all on the stage. I feel I come away from her realizing I have to be 100 percent all the time, and 100-percent present in the music.

Q: You’ve known Henry Threadgill since the ‘80s when you both lived in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood. All these years later, you’re both members of this new class of NEA Jazz Masters.

A: Henry is an inspiration. Not too long ago, he came and talked to my class (at Berklee), and he said something that really struck me. He said, “When I was in school I took every class that the school had to offer.” And he was serious! He said, “I stayed in school for a long time. I was there for the education.” And that stuck with me — the fact that he went to school for the actual purpose of learning, not just to get the degree and learn some things. In other words, if you want to learn, then learn everything you can. Clearly, he has a strong work ethic. That’s obvious in his music — the fact that he’s constantly trying to evolve and better himself.

You hear it in his musical vocabulary and language and with his composing. He’s one of those people that you don’t have to really understand the style or the genre or what he’s doing to realize that it’s special — to realize that it’s great. You don’t even have to like the style. But you know you’re really hearing and seeing and witnessing something that’s very unique and of high caliber. And I think that’s the level we all want to be at.

Q: When we last spoke, the pandemic was just beginning and you described being in a very reflective state of mind — realizing that you’d been in a mad rush for many years. You were stepping back, taking the time to send “thank you” notes to musicians who’d inspired you over the years, like Philip Bailey of Earth, Wind & Fire.

Are you still in that quiet space, or have you gotten busy again?

A: I’ve gotten incredibly busy! Of course, I could say “no” to things, and I am doing that to some degree. But so many cool things are coming up that I just want to do.

Q: What are some of the cool things?

A: I’ve been writing words and music — but lately, more words than music. Like I just wrote the forward to (radio broadcaster and music producer) Mark Ruffin’s book Bebop Fairy Tales. I also wrote the preface for the Geri Allen issue of the University of Pittsburgh’s Jazz and Culture journal. And I’m a Library of Congress scholar, and I just finished writing something for them.

And then I have to compose music, too. I’m co-writing a piece with (trumpeter) Sean Jones and (saxophonist) Braxton Cook for M.I.T. We’re collectively composing a large-scale work on the overall theme of racial justice. It’s a 30-minute, multi-media piece called “It Must Be Now!”

Q: That’s a lot of cool things.

A: Yeah. I’ve been consulting, too. I was curator for The HistoryMakers (the oral history collection, telling stories on video of unsung African-Americans). And there’s also the Visualizing Abolition project at the University of California, in Santa Cruz. I’m curating their music performances that are happening online — Music for Abolition. I did one with Lisa Fischer. Another one was with Nicholas Payton. Jason Moran did one with the choreographer Kyle Abraham. Orrin Evans and Eric Revis did one. Kris Davis. Christian Scott. Nicole Mitchell did one that was amazing. (You can watch the videos here.)

And I’m curating and collaborating on a large-scale multi-disciplinary project next year for the Carr Center (in Detroit) where I’m Artistic Director.

And on top of all that, there’s the institute at Berklee!

Q: You and your band Social Science performed online last month at the GRAMMY Awards Premiere Ceremony, the pre-broadcast show. How did you come up with the band’s name? What does it signify?

A: It spoke to what we’re trying to do. It felt right. It’s not totally literal. We’re not studying human relationships or social relationships, but we’re commenting on humanity and what we feel most needs to change. It’s a transformative lens that we’re trying to look through as musicians, especially when we start working on our new album.

It’s a good way to get things off our chest, to look at the past while considering the present. But the real radical thing is to look toward the future and hopefully to inspire something different — to inspire people to use their own imaginations and consider other possibilities.

SFJAZZ Jazz and Race panel discussion, February 2021

Q: You recently were part of an online panel about jazz and race, sponsored by SFJAZZ. You said you were “pondering” why jazz lags behind other fields in the way it welcomes — or fails to welcome — women. Angela Davis (also on the panel) made a related point: That jazz historically expresses freedom and justice and civil rights — and yet it remains beholden to “a hetero-patriarchy” that ignores the contributions of Black women.

Why is it so slow to change?

A: Why do we still have patriarchy? There are these systems that have supported this idea of patriarchy for a long time — capitalism, sexism, racism, all being extensions of patriarchy. So if you look at the root of the social problems and then you hone in on jazz — you could probably come up with a lot of different possibilities. One could be that in jazz, everybody’s their own company. There’s not the same checks and balances in the way you lead a band or go about your business, as with a corporation or institution. There’s no HR office or CEO that says, “Our donors want you to be inclusive or we won’t get our money.” There’s no system in place for that, and I’m not saying there should be. It’s art.

I don‘t have the answer. But during the civil rights movement, people — including musicians — were not as in tune with the intersection of justice struggles. So a lot of people were fighting for racial justice without fully considering the connection and need for gender justice. And then in the women’s movement, and even earlier with the suffragette movement, you had the same thing where women — mainly white women — were going after a certain a kind of gender justice without connecting it with racial justice. And Black women would just have to wait in line, wait their turn.

Basically we replicate these oppressive systems and that’s kind of what has happened. Jazz just replicated differently and it was acceptable and normal to do so, because that’s what society was doing. Now society is shifting. And sometimes it’s painful, and sometimes it’s amazing. But it’s happening, whether people want to fully embrace it or not. So I’m very confident about the shift I’m seeing, the change that’s happening right now.

And I do know this. If you don’t get with the times when things are shifting and changing, you can get left behind — and it stifles your own growth. And the most exciting part of this particular gender justice movement is that it’s also an invitation for men who have been practicing their art for a long time within this structure— it’s an invitation for them to expand and not necessarily have to perform masculinity if they don’t want to. Because it has been part of the tradition of the music in some ways, right? So I’m excited about this generation and all the young men who gravitate to our institute at Berklee. Because they’re interested in not necessarily engaging in the same ways — as knee-jerk reactions. There are other palettes.

Q: Will you define “performative masculinity” in jazz?

A: It’s the dude-bro culture, connected to what guys do when they get around each other. You hang out with your buddies and it’s going to be a little different when it’s all the guys hanging together, at a party, at a bar, or wherever. They’re going to talk a little different, not be as polite, maybe — “let men be men,” right? And that can go into the music, as well. So this male aesthetic is really all you’re receiving when you’re in the performative space, if that space is male-dominant or excludes women. The feminine energy, the feminine aesthetic, is not being received, and it’s often not present at all.

You could hone in on specific musical qualities, like loud, fast, strong; those are the obvious “male” things.

If you walked today into a museum and saw nothing but male artists on the walls, you’d think, “What’s going on here?” Or at least I hope you’d think that. But nobody thinks that when they go into a club and see no women.

So as far as I can see, jazz — and music in general — is something that’s coming a little slower to that kind of desire for a different possibility in the sound and the aesthetic of the music.

Terri Lyne Carrington with the ACS Trio at SFJAZZ, November 2015

Q: Going back to the panel on jazz and race: You described playing with (pianist) Geri Allen and (bassist) Esperanza Spalding in a trio, and suddenly realizing, “I didn’t know what I was missing.” Did you feel free or safe in a way you hadn’t experienced before?

A: Actually, it’s Geri and Esperanza who were saying that. They felt it more than I did, at least at the beginning. They talked more about it. I was more like one of the guys — a little oblivious.

I probably have a little more masculine energy — though any woman that’s successful in jazz has to be a warrior. So my point is, why? It’s because we’re replicating that aesthetic: “I’m going to play in a way that you can’t tell that I’m not a man, because I can play as loud and strong as anybody.”

I wasn’t really thinking about it when I first got together with Geri and Esperanza. But after a while, I could reflect on it, and I could see that there were things I no longer had to think about in the moment.

Like just being in the club and not having to wonder, “Is somebody thinking can I play or not?” Being a Black woman, you’re dealing with all these microaggressions already.

If I were to take it out of race and look at it from the lens of gender — you don’t want to start feeling like you’re getting paranoid or overreacting every time you experience something like that. Which is something else that someone in the oppressed group has to do — to continually look at themselves to make sure they’re not over-projecting. So coming back to the club, you’re thinking, “Are they thinking I’m not playing loud enough, that I’m not hitting (the drum) like a guy?” All that kind of chatter that goes on in your head; you’re thinking, “Am I making this up?”

So, end of the day with Geri and Esperanza, I still had some of those thoughts — the unnecessary chatter that women have to deal with in their brains.

Q: When you were playing drums as a little girl, did you run into any other little girls with your musical interests?

A: No.

Q: Was it an issue for you?

A: No. I didn’t think of it, because I was a kid. And I was a little bit of a tomboy, anyway.

Q: What inspired you to be a musician?

A: I started so young. I don’t really have a memory of it. I know that my father played music very loud and I’m sure I heard it before I came out of the womb, so I’m sure there was a connection. I felt that vibration. And after I was born, I heard it constantly, and he was playing a lot of blues-based jazz, swinging hard: Jack McDuff and Cannonball and Dizzy and just things that felt good. So that was kind of in my consciousness and so I was immediately attracted to it, especially to organ-based blues.

And I think that was the thing: hearing the music, loving it, and being told that I could do it. I just played along with the records and got that bug and people came to town and let me sit in with them. I think Rahsaan Roland Kirk was the first one. And then there was Clark Terry. So that was my experience, that I got the bug and I then was encouraged to keep at it, doing it in real time with people and being encouraged and supported and applauded for it. And that experience is very unique. It doesn’t happen to a lot of people. And if you put being a young women in the picture, it wasn’t happening very much then — or now.

Q: What happened when you were a teenager? Did you become more aware that there were hardly any other girls doing what you were doing?

A: I didn’t think about it. I was just busy trying to be accepted by all the guys. That was a badge of honor. As a matter of fact, if a woman started talking about it, I’d just kind of move away from the subject. Because unfortunately, I was okay at the time with being one of the few women who was accepted among the guys. But here’s the thing: I wasn’t really fully accepted. I was by some people, but not by everybody — and not fully. I was accepted enough to always work and to get some response and accolades and attention, which helps. But I was kind of tough on women, too. I was like, “Well can you play? Get it together.” I wasn’t really thinking about the scene being tough on women. I wasn’t really thinking about any of that until my 40s.

And now I recognize that women are dealing with imposter syndrome more than men — just the way women question themselves. Like some of my women students say to me, “I don’t want to get the gig only because I’m a woman.” And I always tell them, “Take the opportunity and rise to the occasion.” Because you can best believe that there are a lot of marginal men — and often marginal white men — who take these opportunities. I’ve often said that if I were doing my job the way some other people are doing their jobs, I wouldn’t have a career.

Terri Lyne Carrington's Social Science on NPR's Tiny Desk Concert

Q: Over the last 10 years or so, your albums have had a social justice element — from the first Mosaic recording through Social Science. Is there a thread? What’s the essential theme?

A: I think it changes. It evolves. I’m a different person than I was ten years ago. Art documents your evolution. Some people are maybe more fully formed than others in their early stages. I’m not like that. I’m just one of those people that doesn’t really even want to listen to my previous records or interviews or anything, because I feel like I’m constantly evolving.

If I were to look back years ago — it feels like I’m seeing myself unformed. And I don’t think we ever arrive. It’s the journey that creates the art, that informs the wisdom, and that keeps us going. It’s the art itself, the inspiration to do it, the power of art to inspire and heal. So you just have to be open to whatever the art itself is, or to what the cosmic forces of the universe are telling you as far as your own purpose and mission.

Because you reach a certain age and you start thinking, “What is my legacy going to be? What is this all about?” What are you contributing to the world, and is it really about just having a nice career? That’s okay if that’s how someone feels. But I felt that I wanted to make sure that my contributions are purposeful.

Q: You once told me that you’re basically a shy person. Is it hard for you to be out there as “an activist”?

A: It was, even in this last year. It’s gotten easier, because my patience has gotten shorter. Also, I have more and more experience, and every year my thoughts are more formulated, and I’m trying to get to the next thing. I want to check off some boxes. Because that’s just how I am. And if I can check off the box of patriarchy, that would be a great thing.

Q: Wrapping up, how do you feel about being named a “Jazz Master”?

A: How do I say this? Sometimes you wonder, “Will people think I’m too young?” Because you wonder what other people think, sometimes. And I had to really accept the honor and look at this 40-year career I’ve had — just kind of steadily chipping away at various things. And when you put it all together, I can look back on that and accept the honor. I definitely did not expect it, at least not this soon. And I feel very grateful and appreciative of it, because I feel in some ways it may make people look at my body of work. Because I’ve often felt that people are still discovering me, which isn’t a bad thing, because it keeps it moving. But it’s tiring — very tiring, sometimes — to feel that you’re still proving something at 55. So I feel that this may help in some way, you know what I mean? Maybe there’s a little less of having to prove something. Maybe.

Watch the 2021 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert online Thursday, April 22, 2021 at 5 PM PT (8 PM ET) from arts.gov and sfjazz.org. This is a free event.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.