ALONE TOGETHER:

A Q&A with TABLA MASTER ZAKIR HUSSAIN

November 9, 2020 | by Richard Scheinin

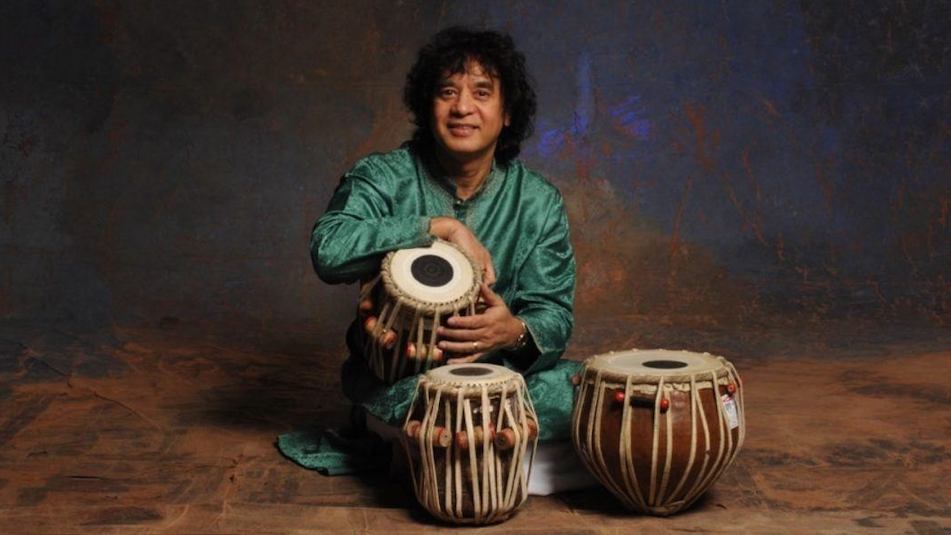

Zakir Hussain

On November 12 (7 p.m. Pacific Time), master percussionist Zakir Hussain performs on a new streaming concert series: Alone Together: Live from SFJAZZ. The 60-minute broadcast — available only to SFJAZZ Members and Digital Members — is part of SFJAZZ’s expanding digital platform, which also includes the Fridays at Five series of streaming archival concerts. Alone Together returns on December 17 with a live holiday show by singer Lavay Smith and keyboardist Chris Siebert.

For Zakir Hussain, past and future are part of the same loop.

The Indian-born percussionist is a lifelong bridge-builder whose collaborators have ranged from Ravi Shankar to Jerry Garcia. In his world, musical discipline is a given, yet rules are made to be broken and discoveries seem always to be around the bend. With that expectation, he is allowing for latitude in his upcoming live-streamed concert from San Francisco’s SFJAZZ Center. Sitting alone on stage in the empty hall on Nov. 12, he will perform centuries-old repertory for the tabla, the Indian hand drums. And he will attempt some futuristic experiments that might include a virtual appearance by one of his famous musical friends. (Keep reading for details.) “In a way,” he says, this open-ended show is “like a guinea pig performance.” With the pandemic shutting down concerts worldwide, it is essential that musicians plow fresh musical ground and that virtual audiences be given something that is expansive, fresh, and even risky: “A certain amount of breath, oxygen, is being pumped into the survival of this music for the next year or so,” he explains.

Hussain is the son of the late tabla master Alla Rakha, who for many years toured the world with Ravi Shankar and once recorded an album with Buddy Rich, Rich à la Rakha. Upon returning home to his family in Mumbai, Alla Rakha invariably would bring along a stack of discoveries: LPs by the Jefferson Airplane, say, as well as Miles Davis, John Coltrane and the Grateful Dead. He would share the wealth with his son who wound up moving west — to Marin — in 1971 and fell quickly and naturally into the San Francisco scene. Barely 20, he began jamming with David Crosby and Carlos Santana, with Jerry Garcia and Mickey Hart. By the mid-‘70s, he was touring with guitarist John McLaughlin and Shakti, helping shape a new brand of Indo-jazz fusion. It was all very organic for Hussain, who says there really were no musical bridges to cross, because, as he has explained, “It was all one land.” In fact, he never stopped performing traditional Indian music: Another early collaborator was Ali Akbar Khan, and, to this day, Hussain performs his father’s own compositions, which sit squarely in the Indian classical tradition.

We spoke to Hussain about his upcoming show and about life in lockdown — a non-stop rush of collaboration, composition, and arts advocacy. He has a new album with McLaughlin and singer Shankar Mahadevan, titled Is That So. He’s just finished composing a chamber work for violinist Joshua Bell, and a new album with Mickey Hart is in the works.

“It’s hard to manage the time,” he says. “It’s nuts.”

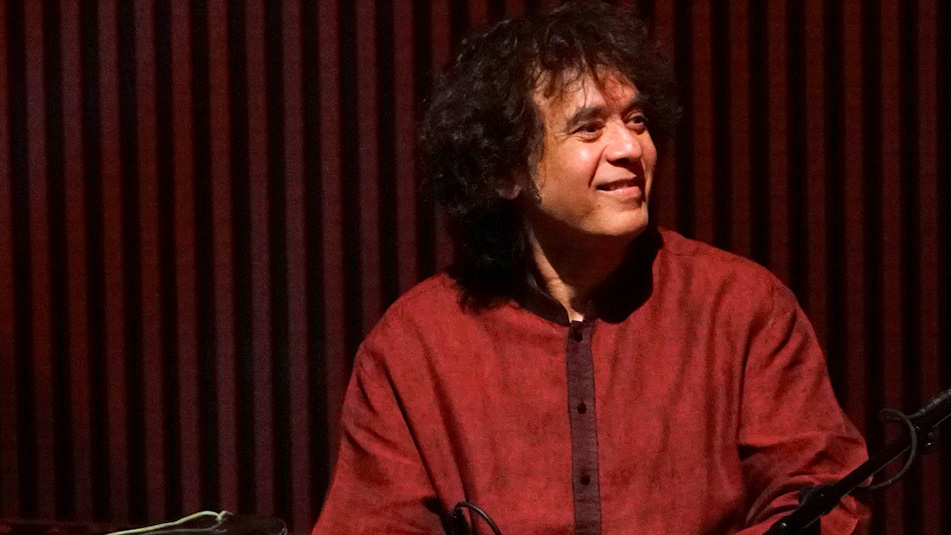

Zakir Hussain at SFJAZZ

Q: It’s funny how busy we all are, never leaving our homes.

A: Exactly. It seems like I’m more busy now than before. It used to be that you just spoke to your management. They took care of everything. They told you, “Okay, this is your flight.” So you just had to get to the airport, get on the plane, get to the hotel and get ready for the concert. Not any more.

Q: How are you feeling about this live-streamed show? You’ll be the only person in the concert hall.

A: I’m a little bit afraid, but in many ways it’s going to be a challenge — an in-depth sharing and baring of what I am. And having said that, I must tell you that I’m sitting in the night, wondering, “What am I going to do?”

Q: What will you do?

A: You should know that there is a considerable amount of repertoire for tabla that is composed and has been handed down over hundreds of years. And so when you play that — as I will on Nov. 12 — the responsibility is there on you to do justice to it. It has all these layers of questions that you should deal with whenever you perform them. And if you don’t, then you’re not paying respect to the form that has been given to you.

Q: Tell me about the composed pieces on the program.

A: I will deal with several such compositions, which I will probably talk about during the performance, explaining where they come from. One of them is about 180-odd years old. The other one is closer to 300 years old. And two are more recent, because they were composed by my dad.

And at the time that he composed one of them, he was very sick; he was almost on his deathbed. And all he could think of was to get all this information collected and passed on to someone. But I was too young; I was maybe three or four years old. Luckily, there were students of his — senior students — who learned it and later passed it on to me. But their interpretation was a bit different from my dad’s.

Q: So you learned the piece second-hand.

A: Yes. And my father recovered. And somewhere along the line — when I was 17 or 18 years old — we talked about the piece. And I’ve recently been playing back his sentences — the various things he told me — in my head. Some of it is on cassettes; I’ve actually been listening. And on Nov. 12, I will try to bring my new understanding of what the interpretation should be.

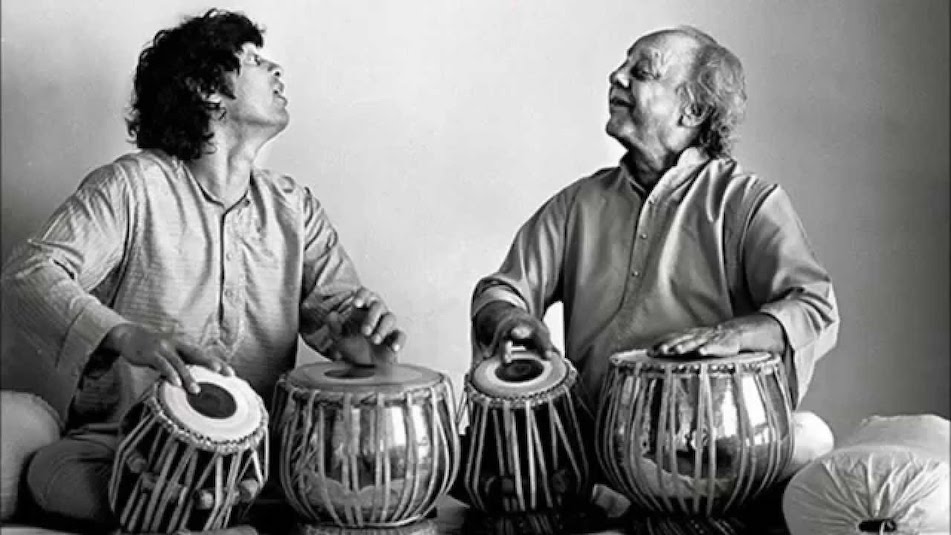

Zakir Hussain and Alla Rakha in recital

Q: When you were a boy and your dad taught you, how would he explain the interpretation of a particular piece?

A: He explained to me where it came from, who the maestro was who composed it, and what was that maestro all about? It’s in a sense a parallel to when a Western classical musician is playing the Bach Cello Suites. Just playing it impeccably, perfectly, and putting it out there like that — that’s one thing. But actually understanding what Bach was feeling, what kind of mood he was in, and where he was and who was around him and all those things — that’s something else. And that realization brings a different understanding of how to handle a certain note or deal with the major or the minor and your interpretation.

And as I’ve approached this concert on Nov. 12, my thought process has taken me way, way back — like hyper-jumping into the past, thinking about what I learned and the lessons I had with my dad. And being a young person at the time, I was happy just to be able to execute the lesson and enjoy myself: “Ah, he told me to do that, and I can do it! Ha ha!” But I was never delving deep enough to get past the surface meanings and understand what he really was talking about. What does it mean to be able to take all that he was telling me and interpret it for myself?

Q: You’ve been asking yourself that question?

A: Yes, and other questions, as well. Is there a part of myself that I have yet to confront and polish and become good at? Are there things that I’ve ignored, different paths I could have taken? All these years I’ve been doing stuff and thinking that I’ve got it, but I really haven’t. I really need to do more hard work! Stuff like that comes forward. And that’s what you’re confronted with when you’re out there alone on the stage in that empty hall. There’s this challenge you face: How much of yourself can you open up to the (virtual) audience?

That’s why I say it’s going to have to be an in-depth baring of what I am — all the layers. I guess it’s going to be me coming to grips with the angels, the spirits, the teachers, the demons — whatever — and walking with them and then through them to be able to present to the audience my arrival at a new understanding.

Q: Aside from the solo tabla pieces, what will you be playing?

A: I’m hoping to have a virtual interaction with one or two of my Indian musician friends. It’s going to have to be some pre-recorded stuff — a traditional composition of a particular raga, and it will be laid out by, say, a sitar player or a flute player. And my hope is to play this pre-recorded music while I interact with it on the tabla.

So I will do that kind of thing. And then Mickey Hart, my dear friend, has offered to virtually attend and maybe play his Beam while I interact with that.

Q: His Beam?

A: He’s got this incredible instrument called the Beam; he’s the only one who has it. It’s a wrought iron slab with very thick gauge strings stretched tightly across it. And it’s solid-body, so it’s very heavy, and it goes through a digital connectivity… and has this wonderful, incredible massive sound.

Now this is not for sure; we have to figure out whether it’s even possible — whether I can have him appear “live” from his home without any latency issues or delays in the sound. Technologically speaking, the challenge is, “Can we have an actual musical conversation?” That’s going to be tough to accomplish. But we’re thinking about it, hoping we can do it.

Mickey Hart demonstrates his Dead & Company equipment, including The Beam

Q: So everything from repertory that’s 300 years old to possibly playing with Mickey Hart on his Beam — that’s a lot of musical territory to cover.

A: Yeah! Because Mickey studied with my father and he knows some of those compositions.

So it’ll be interesting to see if we can put all this together. In a way, it’s like a guinea pig performance — seeing what we can bring into play and therefore make it a bit more fun or interesting for the audience that’s watching.

Q: A few years ago, you told me about your arrival in the United States half a century ago. You said you were lucky — that you found yourself meeting people like Ali Akbar Khan, John Handy, Jerry Garcia. And you decided to test your skills and “walk through the door” — to seize the moment. With this concert, it sounds like you’re preparing to walk through another door. You’re treating it as an opportunity.

A: Yes. It has to be, because we won’t be getting into a concert hall with many musicians on stage and many people in the audience for at least another year. So right now, we must find a way to create a new concert format for virtual audiences all over the world — and with some control, so the musicians will appear to be on the same table, having a conversation. I mean, I can play a tabla solo performance for an hour, by myself, alone in Miner Auditorium (in the SFJAZZ Center) and most tabla players would want to watch it; most tabla students would want to watch it; most Indian music lovers would want to watch it. But how does that help other people who hear me with John McLaughlin or with (bassist) Dave Holland or with (saxophonist) Chris Potter? They want to hear those other elements.

To be able to bring that into play here will be interesting. If Mickey could appear for five minutes and we have a musical conversation, a rhythmic conversation, right there on the spot — people will see that happen. A certain amount of breath, oxygen, is being pumped into the survival of this music for the next year or so.

Zakir Hussain and Dave Holland at SFJAZZ, October 2017

Q: A few minutes ago, you were speaking about the lessons your father gave you as a boy. Did you attend many of his solo tabla recitals?

A: Oh yes, absolutely. There are photographs of me — five years old, six years old, seven years old — sitting with him on the stage. And half the time I was watching him, and half the time I was watching the audience react to him. And as soon as he would start to take his solos, there would be this huge smile on my face, which I just could not stop. And I would turn my head down, because I didn’t want people to think that I was laughing on something, or something was a joke.

It was just this immense joy of being tickled with this information that was being transmitted. And that happiness, that joy, was on his face when you saw my father and this connection he had. I mean, I could probably never reach that level of connectivity with this instrument, because he was at a very pristine, pure level of his relationship with his music. There was no marketing, no business end, nothing like that. We on the other hand have to deal with all these other elements. We don’t have to, but we do. And that takes away a little bit of that clear connection with this incredible art form. And so I’ve tried — that kind of tickle happens when I’m connected with my instrument. It happens rarely, not as frequently as when he played.

Q: This really brings up some deep stuff for you, doesn’t it?

A: (Laughter)

Zakir Hussain and Alla Rakha

Q: What exactly have you been doing over the last eight months of quarantine? What’s a typical day like for you?

A: The first couple of months was like waiting to exhale: “Okay, we’re going to go back to work… back to work.” And then it started to dawn on us that, “No, it’s not going to happen for a while.” So I started doing what I called Z Files, where I went on Instagram, reaching out to all the tabla players across the planet, saying, “This is a free service; join in.” And I would talk about music and talk about playing, and then I would play a little bit and take questions. And it was this Z File that actually started to get me thinking about, “Oh wait a minute, did I really understand this and that composition and the way it should have been played?” It was the Z Files that kind of brought me to this introspection moment.

And then I had been working on the record with Mickey (Hart) before the winter set in. And he wanted us to start to do that again, so we began to do it virtually — me at my home, and he at his place. And we set up this whole electronic thing… all this software that you use to interact in real time and do mixes and listen to the music together and talk about what needs to be done. And I set up microphones in my practice area and I started to play. And the engineer on the other end started to record what I was doing — I began adding to whatever was already laid down last year. And Mickey in his studio was hearing it, so we were able to establish a three-way connection…

And then I started getting calls to do Zoom talks. And then I’m on the board of the National Centre for the Performing Arts in India and on the board of trustees at SFJAZZ. So there have been regular meetings as to what to do through these times we’re in. So that happens. And then Antonio Sánchez, the drummer, asked me to play a 45-minute concert to raise money for the very needy musicians in America, and so we did that. And we’ve been doing similar online events for Indian folk musicians and Indian music teachers who are kind of lost; they don’t even have computers or iPads or anything to be able to work from home. So we were doing that. And then Joshua Bell, the violinist — a Western classical violinist — asked me to write a piece to work with him. So I just finished it. We’re going to record it a couple of days after the SFJAZZ concert. It’s a string quartet, with Joshua Bell and myself as soloists on top of the quartet. So I’ve been doing that.

Q: Where will you record it?

A: In San Francisco.

And then, you know, usually I do a retreat every late summer with all tabla junkies from all over the world. They come here to Marin — like 40 or 50 of them — and then we just spend many days together, morning until night, late nights, just doing tabla. And I couldn’t do that live, so we did it on Zoom. And so I did many days of that, many hours a day. So there’s been a lot that has happened so far. And it has kept me busy and there has been time enough to be able to go back to the past and then back to the future!

Q: A couple of weeks ago, in an interview with Rolling Stone, you also mentioned spending time in the garden with your wife — and watching Masterpiece Theatre. So you must have a little down time.

A: Yeah, just about half an hour or 40 minutes in the garden. And Masterpiece Theatre is when I’m in bed late at night.

Q: What have you been watching?

A: Lately I’ve been watching Hercule Poirot — the Agatha Christy series. I’ve read all those books, but I never saw them recreated in a movie form or a TV series form. So that’s what I’ve been watching lately. It’s only about 50 minutes long, each episode, so I can see one, and that’s it. And this actor David Suchet is really a pretty decent Hercule Poirot. So I’m glad to catch up with that. The series is some years old; I just never got around to it. My wife watches Downton Abbey and I watch this.

So that’s what I’ve been doing. And hopefully this is going to be fun on Nov. 12. Many a time, I’ve been thinking about these compositions by my dad, and I go back in my mind and it is quite emotional and sometimes brings tears to my eyes. I hope it doesn’t happen at the concert. We’ll see.

Zakir Hussain at SFJAZZ with Steve Smith, Eric Harland, Giovanni Hidalgo

Zakir Hussain performs a live-streaming concert from the SFJAZZ Center on Thursday, November 12th (7 p.m. Pacific Time). The cost of viewing the show — available only to SFJAZZ Members and Digital Members — is $10. Details here. To become an SFJAZZ Member, click here.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.