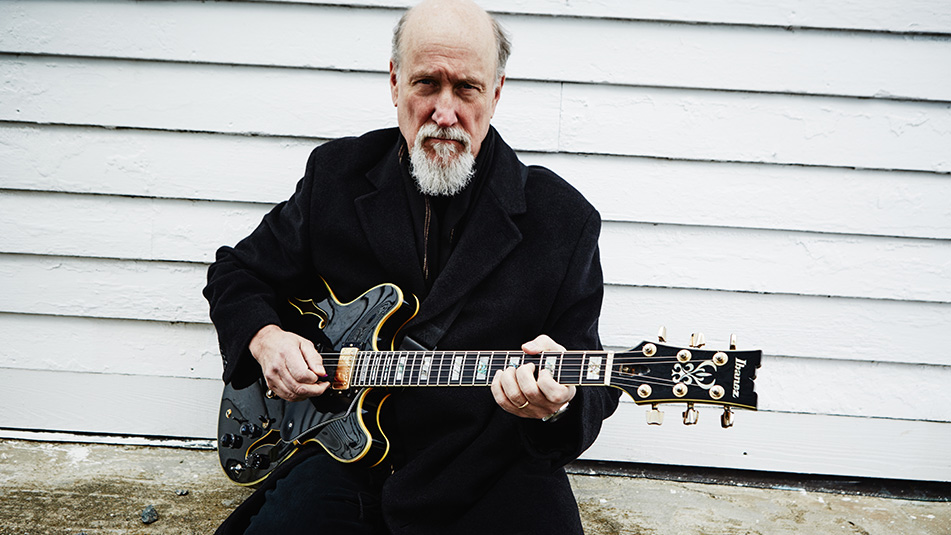

John Scofield's Outside-In Approach To Jazz

July 2, 2020 | by Richard Scheinin

Ahead of guitar giant John Scofield's week at SFJAZZ with funk/jam juggernaut Lettuce in March 2019, SFJAZZ staff writer Richard Scheinin spoke to Scofield about his momentous career as one of the most influential guitarists in modern music. The article focused on Scofield's then-new Verve quartet album Combo 66. Last month Scofield released Swallow Tales, a new recording for ECM featuring his longstanding trio with drummer Bill Stewart and bassist Steve Swallow dedicated to Swallow's compositions.

As we look forward to this week's Fridays at Five streaming concert featuring a performance from Scofield's 2019 run with Lettuce, we take a look back at this enlightening talk with the guitarist.

Guitarist John Scofield’s new album is called Combo 66. It refers to the fact that Scofield is 66 years old and it riffs on the titles of some of the jazz LPs he grew up with, including Bill Evans’ Trio ’64. Then again, Scofield, who has been on the road for 40-plus years – with Gerry Mulligan, with Miles Davis, with Gov’t Mule, with his own bands – knows a lot about the nation’s highways, so Combo 66 also puts him in mind of Route 66. He wrote all the tunes for the album while on the road, and, naturally, his new Combo 66 quartet – which performed at SFJAZZ on Oct. 21 – already has spent months playing those compositions while touring the U.S., Europe and Asia: “We haven’t gotten completely sick of the songs,” Scofield jokes, mentioning that he already is writing new material. A man of many projects, he has a mania for keeping things fresh: “You have to keep adding stuff, because a band is like a monster machine or like an animal that needs to be fed.”

Combo 66 is a straight-out-of-New-York jazz session for the guitarist, who grew up in suburban Connecticut, spent years honing his skill-set while gigging around Manhattan, and still lives just north of the city. On the album, Scofield nods here and there toward a blues-and-roots feeling – one of his trademarks – but this is mostly refined straight-ahead jazz playing by top players: drummer Bill Stewart, who has worked with Scofield for nearly 30 years; pianist Gerald Clayton, a young gun whose keyboard touch Scofield likens to that of Hank Jones and Tommy Flanagan; and bassist Vicente Archer, who is “great at bass function, and what I mean by that is he loves to support the band on the bottom end,” Scofield says. “He’s great at walking. He can really swing. And Vicente” – who also performs in groups led by Robert Glasper and Nicholas Payton – “can push the band. He loves to play funk, and he can play free. He’s super-versatile. All these guys can play all sorts of ways, which is kind of the way I like to play, too.”

Name another musician whose résumé is more varied than Scofield’s. He has worked with Charles Mingus and Jaco Pastorius, Herbie Hancock and Eddie Palmieri, Joe Henderson and Eddie Harris, not to mention gospel singer Mavis Staples, classical composer Mark-Anthony Turnage and Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead. For four nights next spring (March 21-24) Scofield will play at SFJAZZ with Lettuce, the funk-jam band with which he has been associated since 2002. He talks about Adam Deitch, Lettuce’s drummer, in much the same way that he describes Archer, as a player with an all-embracing aesthetic: “Adam is probably 25 years younger than me and really comes from a different scene. But he loves jazz and he can play the shit out of funk and Afrobeat and all this cool stuff and he’s a real musician. I met those guys” – the members of Lettuce – “when they were doing kind of a Tower of Power thing years ago, and they were really good at it. Then last year they invited me to play New Year’s with them at the Brooklyn Bowl, and I just loved it. I thought they’d really blossomed as a group: It was so musical and it made me just so happy to play with them. It was just house-rocking and the whole place was like a funk festival. Those guys really capture something.”

Significantly, Scofield – whether he’s playing “On Green Dolphin Street” or funk – has a consistent approach. As an ensemble member, he listens hard and doesn’t overplay. His solo lines bob and weave. They float. Sometimes they get sassy, curling up to a bluesy, bee-sting climax. Basically, he often has said, he takes the music he heard as a kid – folk, blues, rock, whatever – and turns it into jazz. His musical appetites go beyond genres, but jazz remains his compass: “I’ve basically spent my life learning to play bebop.”

John Scofield with Miles Davis in 1984 (Photo by Jan Persson)

Scofield, who grew up in suburban Connecticut, made his debut on guitar as a sixth grader: “It was playing `Greensleeves,’ the chords, while this other kid, Timmy Cunningham, sang,” he says. “And then I remember learning `House of the Rising Sun” and Beatles songs and `Louie, Louie.’” By 1966, when he was 14, he was taking the train to New York and hanging out at Manny’s Music, one of the stores on “Music Row” along West 48th Street. “One time I went there – it was 1966 – and I bought my first expensive guitar, a Fender Telecaster, and do you know who else was there? Bob Dylan was in Manny’s, with his hair sticking out, and he was buying a guitar, too. It was crazy. My father was with me – he paid for the Telecaster – and he went and asked Dylan for his autograph and he gave it, begrudgingly.”

By this time, Scofield had become “an obnoxious suburban blues snob. I learned to play a few blues licks and really fell in love with the blues boom that was happening. From ’66 and onward, B.B. King and Albert King and all those guys were starting to play for white audiences, basically. Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Rush, Junior Wells with Buddy Guy – I would go and hear those guys. There was this club on Bleecker Street called Café Au Go Go. They had this thing called the `Blues Bag,’ which was like a festival. And this one time – I think it was ’66, maybe ’67 – they had the Blues Project and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and I was into those bands. But I remember that same night they also had B.B. King, Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, Big Joe Williams, solo – I mean they were all there in one night. It was, like, amazing.”

In 1969, Scofield saw Jim Hendrix perform at Hunter College in New York: “He threw down so heavy, it was overwhelming to me,” he recalls. “The power of his blues – I just thought, `Forget it, this guy is the best there’s ever been. I’ll never be able to do that. But maybe if I just practice jazz enough, I’ll get good at that.’ Can you believe I actually thought that? I had no idea what was involved. I was already trying to play jazz. I was taking lessons. I had my Jim Hall records and my Wes Montgomery and Pat Martino, but I was clueless.”

Maybe so, but Plan B – jazz – worked out. Scofield attended the Berklee College of Music, dropping out in 1973 to play with Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan. He toured with Billy Cobham and George Duke. He was one of three guitarists – the other two were Larry Coryell and Philip Catherine – to record with Mingus on the bassist’s Three or Four Shades of Blues LP. When Pat Metheny left Gary Burton’s band, Scofield replaced him. Soon he began to form his own groups: fusion, funk, bebop, free.

He credits this constant diversity to “my early background in the ‘60s, where there was all this cool music that wasn’t jazz – being open and into that has allowed me to play in all sorts of situations. Phil Lesh doesn’t hire me because I’m a great Grateful Dead guitar guy. I’m not really even a Grateful Dead fan, though I’ve come to appreciate what they do. He hires me because he wants a guy who can stretch out and turn the Grateful Dead into free jazz.”

Similarly, Scofield says, “I’m not really a jam band guy. I don’t listen to those groups. But this is my feeling about the jam band thing: It reminds me of the early ‘70s in New York when I first started to go to the Fillmore East, when there’d be Santana along with Miles, and there’d be Charles Lloyd along with Doc Watson and bluegrass and blues. And the jam band world allows for all that. Plus, in any idiom, you’ll have these talented people. It could be polka music.”

For all his open-mindedness, Scofield, at age 66, has grown judicious about choosing new projects: “I try not to waste time, because there’s very little time left,” he says, matter-of-factly. He picks his shots, and not necessarily the convenient ones. He has decided to play a few solo shows in Europe next year: “It’s something I’ve toyed with over the years, but never really gotten down. Because solo guitar playing is really hard, and so I’ve been practicing.” And, yes, he still loves “to play `On Green Dolphin Street’ and that kind of music,” he says, when asked if jazz standards continue to hold the old allure for him. “I just love that music, and that music continues to challenge me, and so I keep playing it and I keep learning standards. Because I’m a music fan first.”

At a time when many musicians eschew the word “jazz,” because they find it limiting or irrelevant or not helpful to their marketing strategies, Scofield pledges his allegiance to the form: "I’m a jazz musician – I hope," he says. “I aspire to be like the great jazz musicians who were jazz musicians when I was a kid, like Miles Davis and Mingus and Gerry Mulligan. I know Miles was one of the guys who said, `I don’t like the word jazz.’

Scofield pauses, then says, “Shit, what’s better than jazz?”

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.

Originally posted September 21, 2018