Freedom and wonder:

A Q&A With Charles Lloyd

September 19, 2022 | by Richard Scheinin

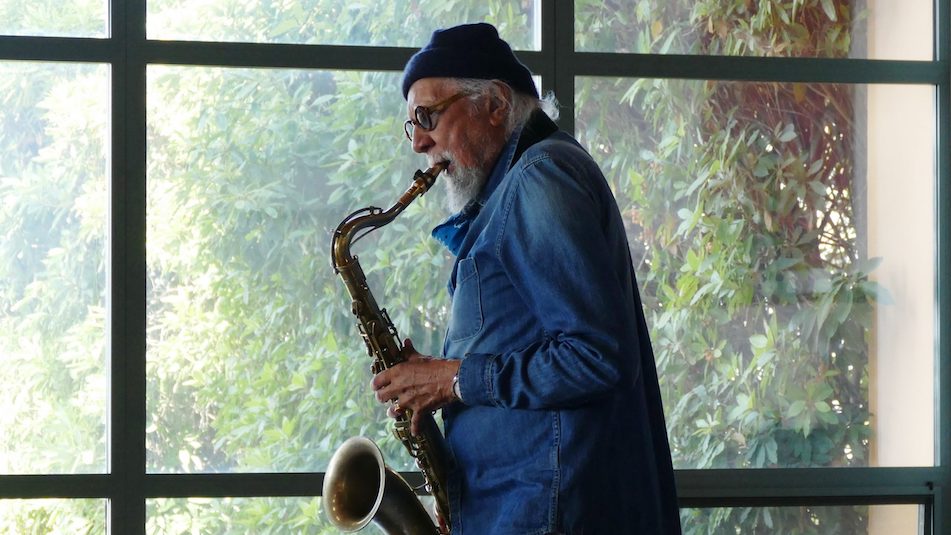

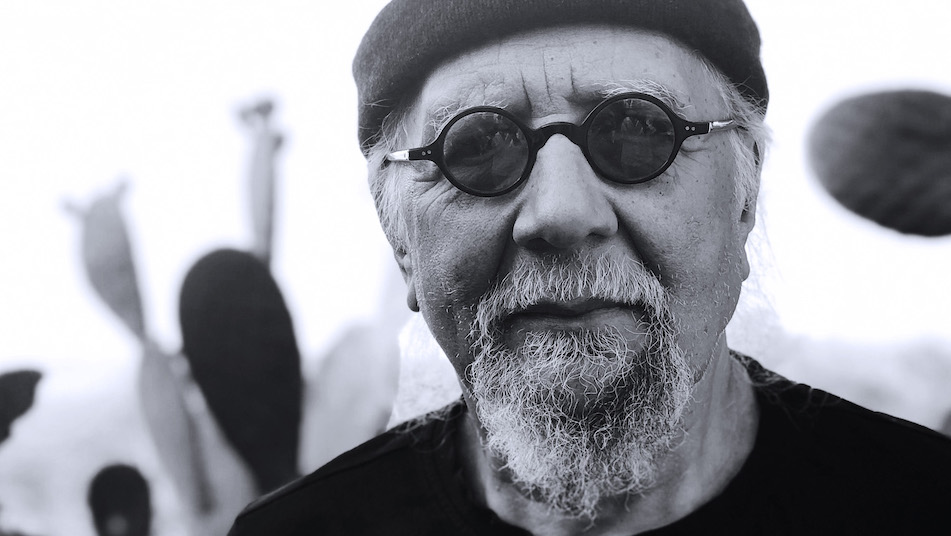

Charles Lloyd (photo by Dorothy Darr)

Beginning September 29, Charles Lloyd returns for four nights with three remarkable trios. Staff writer Richard Scheinin spoke to the saxophonist, composer, bandleader, and 2015 NEA Jazz Master about his career and upcoming performances.

Eight years ago, when I last spoke to saxophonist Charles Lloyd, he suggested a one-hour phone conversation. It stretched to two. Basically, I sat back and listened as he told stories about his friendships and encounters with Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Ornette Coleman, Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, novelist Ken Kesey, Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, Robbie Robertson of the Band, actors Larry Hagman and Peter Fonda, painters Larry Rivers and Kenneth Noland, comedian Dick Gregory, and race car driver Wolfgang von Trips.

Last month, when I got back in touch with Lloyd, who is about to begin a four-night residency at SFJAZZ (Sept. 29-Oct. 2), I told him that he can seem like the epitome of the Private Man. He speaks like a mystic and has gone through periods living almost as a hermit. Yet his world, clearly, is also very large: “How do you explain this?” I asked him. “How are these two aspects of your life connected?”

Lloyd, who is 84 — a renowned bandleader and instrumentalist for nearly 60 years — answered with one sentence: “A Life is not experienced in one key or in one lane.”

He capitalized “Life” — this time, our interview was conducted via email — and proceeded to tell stories about Big Mama Thornton, Elvis Presley, trumpeter Booker Little, and, again, his friend Dick Gregory.

Born and raised in Memphis, Lloyd is steeped in the blues — as a teenager, he played with Howlin’ Wolf. In the ‘50s, he moved to Los Angeles to attend the University of Southern California and fell in with some of the heaviest jazz innovators: Ornette Coleman, saxophonist Eric Dolphy, drummer Billy Higgins, vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, big band leader Gerald Wilson. He has stories about all of them.

Moving to New York, he emerged as a leader. In 1966, he recorded the million-selling Forest Flower at the Monterey Jazz Festival with his quartet, the group that put Keith Jarrett on the map. Over the next few years, Lloyd became a star, operating in the post-Coltrane firmament, but cooking up his own brand of swirly, spiritualized folk music. He performed opposite Joplin, the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium, where he recorded an album titled Love-In. He hung out and recorded with the Beach Boys during their arty period. He also “indulged,” burned out, dropped off the scene, and entered a reclusive period of spiritual questing — followed by decades of music-making around the globe as a beloved elder of jazz.

Lloyd, who lives in the hills above Santa Barbara with his wife, artist Dorothy Darr, remains remarkably active, leading trios, quartets, and a quintet that he calls The Marvels, featuring guitarist Bill Frisell. This year, he is releasing three trio albums on Blue Note Records — a “trio of trios” — and he will bring three different trios to SFJAZZ, featuring the likes of Frisell and percussionist Zakir Hussain. Each night should be intimate and personal, offering new marvels from this life-long quester and musical storyteller.

Here is the full transcript of my interview with Lloyd.

Q: When we last connected, you talked about playing music of “freedom and wonder.” And you mentioned being “drunk with music.” Can you define those terms — and tell me if being drunk with music is ever a problem?

A: When I was little, there was so much racism and repression in the South. Music was my path to freedom — and every time I heard music, it filled me with an indescribable sense of wonder.

When a honeybee dives deep into an open flower to drink up the nectar, it dives deeper and deeper to become sated from the sweet elixir. As it flies out with its legs laden with pollen, it appears to be in an ecstatic state. That’s how I feel when I make music.

Q: What is your earliest musical memory? How vivid is it?

A: When I was growing up, I used to spend summers and vacations on my grandfather’s farm in Mississippi. Mr. Poon, who lived on the farm, used to play guitar and sing — kind of like Robert Johnson. My cousin and I were enthralled. Around this time, one of my aunts took me to a parade where I saw and heard a saxophone. (I had seen one in my grandfather’s attic and was entranced by it, but I had never heard one.) A light went off and I said to myself, “That’s what I’m supposed to do.”

Q: You’ve told me about playing with the old blues musicians Rosco Gordon and Roosevelt Sykes — but not about Big Mama Thornton. What was it like to play with her? Can you describe her presence? The impact her music had on you?

A: She was a tough, pistol-packing Mama. She could belt it out there: “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog!” She sang that long before Elvis. After the gigs, Big Mama would take the little guitar player and put him in another kind of service. She was a mighty force to be reckoned with.

Q: You knew Elvis in Memphis?

A: Elvis drove a delivery truck around Memphis. He used to come to the “Plantation Inn” across the river in West Memphis, Arkansas, and listen in. This is when I was playing with Phineas Newborn Sr.’s band. Phineas Jr. had put me in the band with him and his brother, Calvin. Calvin wiggled his hips and jumped in the air when he played his guitar. Elvis saw that and took it all the way to the bank.

Q: You often mention Booker Little, your best friend in high school. Do you ever dream about him — and about Billy Higgins, another departed friend? If you do, what do they tell you in your dreams?

A: Booker and Master Higgins visit me all the time.

Q: Were you ever a “jazz purist”?

A: What is a jazz purist? I’m a music maker. When you love music, you love a lot of it.

Q: What is the key to crossing “genre boundaries” while staying true to the music? It seems like it’s never been a problem for you, whether you were making music with Mike Love or Roger McGuinn or Lucinda Williams. But that’s not true of everyone who crosses genres. What’s your secret?

A: When I am making music, I try to get out of the way and let the music come through. I am simply the vehicle. It is the same model vehicle that it was when I landed on the planet 84 years ago — but I try to keep it in good running order. Regular tune-ups and all.

Q: You began meditating in the mid-1960s. What is the relationship between meditation and your tone and sound? Is there also a connection between “good character” and your tone on the saxophone?

A: Big-time connection — that is where Booker comes in. When I moved to New York City, I stayed with him for the first several months. We stayed up late talking about music and life... It always boiled down to Booker telling me that “it’s not about the fast lane — it’s about character.” He still speaks to me every day. The legacy of the music he left us with reveals his incredible genius.

I have had the blessing of a long life. Experience and intense work on my character are reflected in my tone.

Q: Generally speaking, what are your non-Western musical and cultural influences, and when did they first begin to influence your music? Why do you think you’ve always been so “open”?

A: Africa — I moved to New York City in the early ‘60s and when I wasn’t out touring with Chico (Hamilton) or Cannonball (Adderley), I used to play with Olatunji. He was a beautiful soul and I learned so much from him.

India — When I was studying at the University of Southern California, Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha performed in LA. That’s when I heard the call of Mother India — not only the music, but poets like Tagore and the saints such as Milarepa. Later, I found my way to Ramakrishna and Vedanta. I was also deeply moved by Ali Akbar Khan, the sarod player. His sons Aashish and Pranesh are on my album, Geeta.

Q: Why do you play with so many different bands?

A: It’s all a part of the whole.

Q: And why this emphasis lately on trios? What is it about the trio format that appeals to you?

A: There is a lot of space and air in a trio setting. The interplay between instruments is intimate and personal.

Q: Could you speak briefly about the three trios you’ll bring to SFJAZZ? The first two nights, you won’t have a drummer. Why not?

A: This year Don Was, (the president) at Blue Note Records, wanted to release something special and a little different. I had a couple of trio concerts during the COVID shutdown and a couple other recent trios with different musicians. Don loved the idea of releasing a “Trio of Trios” — thus this series of releases. Chapel came out in June. Ocean comes out September 23 — and the last, Sacred Thread with Zakir (Hussain) and (guitarist) Julian Lage, comes out in November.

Q: Tell me briefly about the Chapel Trio — with Bill Frisell and bassist Thomas Morgan (performing Sept. 29).

A: The Chapel Trio is named after the Coates Chapel in San Antonio. I had been shown this space a couple years earlier and knew the acoustics would not be friendly to percussion — so when I was invited to give a concert in the chapel, I thought of Bill. I knew that Bill and Thomas had recorded in duo and had a close musical rapport, so we decided to invite Thomas to join us. It was a magical night.

Q: How about your trio with pianist Gerald Clayton and bassist Reuben Rogers (which performs Sept. 30)?

A: Reuben has been playing with me almost 20 years — we have shared a significant time together in music and in friendship. He is both an explorer and an anchor. Gerald joined us around 2013 when (pianist) Jason Moran had to miss two concerts of our spring tour to be able to take care of his young boys. I had met Gerald when we were in Brazil — I knew he had big ears and a passion for the music. Gerald has grown into a beautiful, expressive poet of the keyboard. He and Reuben have played together a lot with me in quartet or quintet settings. The three of us have an established rapport and language in the music — but this will be the first time we have performed together in trio. Since these dates at SFJAZZ coincide with the three trio releases, I thought it would be interesting to present three different trios over the four days.

Q: And please tell me about your trio with (tabla master) Zakir Hussain and (guitarist) Marvin Sewell (performing Oct. 1 and 2).

A: Nearly five decades after first hearing Ravi Shankar, John McLaughlin invited me to his concert at UCLA — he wanted me to come down to hear Shakti. I was so moved by the music they were making together. John sounded beautiful, and hearing Zakir on the tabla took me back to Howlin’ Wolf — and I don’t know how you can make that analogy, or that jump, but when I played with Howlin’ Wolf as a teenager, it shook me to my core, and when I heard Zakir I had that same kind of shake deep inside of me.

When we met, he told me that when he heard Aashish and Pranesh on my album Geeta, he thought it should have been him. A connection was made. It was then I learned that Alla Rakha was his father, whom I saw playing with Ravi Shankar at USC, so it has been like that — connections on a journey. Zakir and I played together in concert for the first time in October 2001 at Grace Cathedral — it was Randall Kline’s idea. (Kline is founder and Executive Artistic Director at SFJAZZ.) As it turned out, it was only a few weeks after 9/11; it was very emotional for us. Someone had threatened to bomb the Golden Gate Bridge the afternoon of our performance — Zakir told the audience, “Music is about building bridges, not destroying them.”

Marvin is a beautiful soul and great musician — he comes out of Chicago with roots in Mississippi. We share the Delta experience and it is reflected in the music we make together.

Last December I had a residency at the Pierre Boulez Saal in Berlin. One of the nights was the Chapel Trio, the other was this trio with Zakir and Marvin Sewell.

Q: I’d love it if you would tell me a little more about your relationship with Zakir. You’ve performed with so many fantastic drummers — Billy Higgins, Tony Williams, Jack DeJohnette, Billy Hart, Eric Harland. Even so, I imagine that Zakir is special to you.

A: Zakir brings so much with him… He comes from a divine lineage of centuries of tabla masters. He is a deep and beautiful Soul. In 2004, I had a concert at the Palace of Fine Arts (in San Francisco). I wanted to pay homage to Master Higgins, but I did not want to try to duplicate the special duo formation that he and I had. Eric Harland had recently joined my group and he was finding his voice. So I decided to try Zakir and Eric together with me. It was an amazing night of discoveries which grew into our recording Sangam.

Q: I get the sense that your bandmates are not “just” bandmates — that they are “Kindred,” which is a term you used in an album title a few years ago. Am I correct? And what is it like to play with Gerald Clayton and Anthony Wilson — they are children of musicians you’ve known through the years. What are you learning from these younger players? Guitarist Julian Lage is another.

A: Gerald comes from a lineage of great musicians — it has been a joy to witness his growth as a musician over the last 10 years.

In the case of Anthony — I was in his father, Gerald Wilson’s, big band when I was a student at USC. He was two decades my senior, but we shared common roots in Memphis. Being in his band was an important part of my growth as a musician. Gerald was not only a great band leader, but a great composer. Anthony grew up under the wings of his father and is also a great composer and musician. He has worked for many years with Diana Krall and recently took a sabbatical from touring to research his Southern roots.

I first met Julian when he was 12. I was performing at the Healdsburg Jazz Festival, and Jessica Felix (the festival’s founder and then artistic director) asked me to let Julian sit in with us. John Abercrombie and Master Billy Higgins were also in the band. I think John was bowled over by the promise Julian showed — we both knew he was going to grow into an extraordinary musician if he stayed on the path. He did, and he is an extraordinary talent. He is on Sacred Thread with Zakir.

Q: I’ve heard that Dick Gregory introduced you to vegetarianism. Is that true? Were you good friends?

A: Greg and I used to share the stage at the Village Gate and other venues in the 1960s. We became friends. When I had my 75th birthday at the Kennedy Center, he was their “surprise guest.” They were worried about what he would say — but he was magnanimous and marvelous. The next day, he came to my hotel and we spent the next four hours in deep conversation about the whole thing.

Q: You are 84. How does being an elder shape your music and your sound? Do you ever feel like you are slowing down?

A: I have lived long and have the benefit of experience. It is reflected in my sound.

Q: When you look back on your life, does it just seem “normal” — like, “Well, sure, that’s just the way it happened, and it’s still happening.” Or does it seem dreamlike or surreal? Do you ever scratch your head and say to yourself, “How did all this happen to me?”

A: I have been blessed throughout my life. The blessing continues. I still have work left to do. Of course, I have slowed down — I don’t run up and down hills anymore, but I have beginner’s mind and each time I play it is like the first time. It is another chance to tell the Truth.

Q: Is there anything you wish you could tell your younger self?

A: Straighten up and fly right.

Charles Lloyd performs from 9/29–10/2. Tickets and more information are available here.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.