A Message Behind the Music:

Jazz and Social Justice

February 16, 2021 | by Richard Scheinin

Album artwork from Max Roach's 1960 album We Insist! Freedom Now Suite

In recognition of Black History Month and next week's Fridays at Five streaming concert featuring vocalist Paula West's "Great American Politic," we take a look back at SFJAZZ staff writer Richard Scheinin's piece previewing the April 2018 Jazz and Social Justice week that included West's program of timeless political songs.

From the beginning, jazz has been a force for social change. You can feel it in the energy of the music, in its urgency, in the wailing of saxophones and in the pronouncements of trumpets – a crying out for justice. At the height of the civil rights movement in 1964, Martin Luther King, Jr., observed how “much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.”

Honoring the music’s historic role as a catalyst for change, SFJAZZ is presenting a week of programs devoted to the theme of Jazz and Social Justice (April 18-22). Trumpeter Terence Blanchard is central to this special event. Among today’s musicians, he has a keen understanding of the ways in which jazz can respond to social conditions and political situations. His compositions have reflected upon the life of Malcolm X, the victims of Hurricane Katrina and the death of Eric Garner, who whispered, “I can’t breathe” while a New York police officer kept him locked in a chokehold. Blanchard’s new album, LIVE, is a response to gun violence and particularly to police shootings of unarmed black men.

I think music and art have the ability to make people reflect, to make people question, and in some cases to make people come to terms with things. The way I look at it, art is the social conscience of the country.

TERENCE BLANCHARD

Terence Blanchard

Blanchard and his E-Collective will perform selections from LIVE at SFJAZZ. The week also will feature vocalist Paula West (interpreting songs by Bob Dylan, Paul Robeson, John Lennon and Nina Simone) and percussionist John Santos (playing Afro-Caribbean anthems of resistance). Significantly, a pair of younger bandleaders, drummer Jaimeo Brown and pianist Samora Pinderhughes, will demonstrate how a new generation is extending jazz’s activist mission. “I don’t want to just be this selfish guy who plays the piano without making a material impact on the way people live,” says Pinderhughes, a Berkeley native whose parents are community organizers. His Transformations Suite – he performs it April 19, part of a double-bill with Brown – draws on song and the spoken word to address social issues including prison privatization and income inequality.

Spanning generations and geographic regions, these shows should make for a fascinating streak of programming. To get audiences ready, the week will open (April 18) with a listening session (with author, educator, activist, and Civil Rights icon Angela Davis) moderated by Executive Artistic Director Randall Kline. One can imagine some of the recordings to be played and discussed.

Candidates include Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” recorded in 1939 as a eulogy to the victims of lynchings across the South; their bodies are the “strange fruit” hanging from the poplar trees. Charles Mingus’s “Fables of Faubus” dates to 1959 and calls out Arkansas’s segregationist governor Orval Faubus. John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” from 1963, is a lamentation for the four little girls killed that year in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Even after all these years, Coltrane’s composition evokes the immense pain and sadness of that loss. In a sense, it is part of the jazz soundtrack to the era. Other tracks would include Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam,” from 1964; Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not be Televised,” from 1970; and Archie Shepp’s “Attica Blues,” from 1972.

> Listen to SFJAZZ's curated "Freedom Now!" playlist

With LIVE, Blanchard (April 21, two shows) could be adding to the canon.

The new album was recorded during live performances by his E-Collective in Cleveland (where 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot by police while playing with a toy gun in 2014) the Twin Cities (where 32-year-old Philando Castile was shot during a routine traffic stop in 2016), and Dallas (where five officers were killed by a sniper during what had been a peaceful march against the wave of shootings by police.) Over the last year, Blanchard says, these and related news stories have somehow faded from public view, because the political reality show in the White House keeps driving attention elsewhere: “Do you hear anybody talking about police violence? The NFL players were taking their stand, taking a knee, but the story gets turned around and made into something about patriotism. Oh really? People are getting killed. Where’s the patriotism in that?”

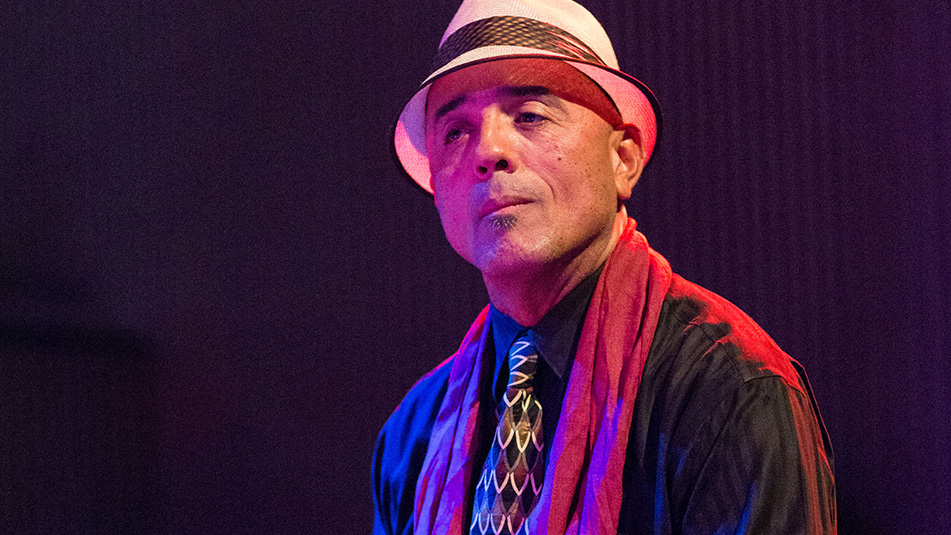

Paula West at SFJAZZ (Photo by Grason Littles)

Every artist “speaks what their truth is,” adds West (two shows April 20, and an added show April 7) who is choosing her repertoire in response to the politics of “you know who.” She expects to include the Beatles’ “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and will create a medley of songs about the insidiousness of racism: “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” (from the musical “South Pacific” by Rodgers and Hammerstein) and “Turning Point” (popularized by Simone). And she won’t pass up Lennon’s “Gimme Some Truth,” recorded in 1971 as a response to President Richard M. Nixon and the Vietnam War.

“But it feels like it could’ve been written yesterday,” says West, who is distraught over “how messed up things are. I never thought I’d ever experience something like this in my lifetime, ever. And I have nothing to lose in speaking my mind. I don’t look at it as my responsibility so much as I don’t have a choice.”

As an African-American art form, jazz – almost by definition – has historically carried a message beyond the music.

“The western concept of art for art’s sake is something that doesn’t exist in African and indigenous forms and culture,” explains percussionist Santos, who grew up in a Puerto Rican household in San Francisco. “The art itself is functional. It’s more like art for life’s sake; there’s always a deeper meaning. In this country where jazz was born, the art by nature is political. We’re not bringing politics to the art; the art is born from our political and social reality.”

Through the music, in other words, there is a connection to history as well as to the routines and rhythms of daily life. Santos remembers how his grandfather Julio Rivera, a professional musician, performed at home every weekend to a room packed with dancers, while the smells of his grandmother’s cooking wafted through the house. The music was a celebration and – subconsciously, at least for some – a connection to traditional religion, to the ancestors, to history.

John Santos at SFJAZZ (Photo by Drew Altizer)

At his concert (April 22), Santos and his group will perform a piece composed by guest percussionist Juan Gutierrez.

“It’s a bomba, a kind of Afro-Puerto Rican music of resistance,” Santos says. “It comes from slaves on the sugar plantations and it almost disappeared – the most African music we have in Puerto Rico. It was largely preserved by a couple of families and now young people of all colors and walks of life are embracing it, which I find miraculous. This is a tradition we share with jazz, with Duke Ellington’s `Black, Brown and Beige’ suite, with Coltrane’s response to the Birmingham bombing, with Charlie Mingus and Charlie Haden and down the line – this idea of instrumental music that is inspired by the struggle.”

The art itself is functional. It’s more like art for life’s sake; there’s always a deeper meaning.

John Santos

Growing up in the 1950s, Ishmael Reed – SFJAZZ’s poet laureate from 2013-2015 – looked to jazz for a new kind of proud, politicized role model: “If it hadn’t been for Max Roach and Diz, we would’ve been in reform school.” They showed Reed and his friends an effective way to function in the world: to be creative and “in your face. When this club owner told Tadd Dameron and Bird they couldn’t drink from his crystal glasses, they smashed the glasses. They showed that you didn’t have to bend down and be passive. Jazz musicians didn’t give a fuck.”

Their music expressed the urgency of the times.

Reed ticks off a bunch of album titles: Freedom Suite, by Sonny Rollins, We Insist! Freedom Now Suite by Roach and Abbey Lincoln, Let Freedom Ring by Jackie McLean. As a lyricist and poet, Reed has been inspired to collaborate on his own freedom songs with musicians including David Murray, Carla Bley, Eddie Harris, Gregory Porter and Taj Mahal. With the composer Carman Moore, he created the gospel opera Gethsemane Park, which he describes as “a Voudoun reading of Jesus’s arrest by the Romans.” Only the action has been moved from the Garden of Gethsemane to a homeless park in Oakland.

Samora Pinderhughes

Pinderhughes is only 26, but he draws similar inspiration from the music’s fight-the-power tradition. He names some of his own heroes: Harry Belafonte, Simone, Holiday, Coltrane, Mingus and Roach. He admires their “radical imagination” and their determination to expose “the reality of oppression.” In fact, Pinderhughes – who works with an activist network called Blackout for Human Rights – sees a metaphor for community activism in jazz and musical improvisation. All involve “creating from scratch. It’s the exact same thing we’re trying to do as a society. We’re stuck in all these patterns and we have to break out and imagine our way forward. Every time, we have to find the groove. We have to invent the future.”

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.

Originally posted March 20, 2018