2021 NEA JAZZ MASTERS:

A Q&A with music director Miguel ZenÓn

April 7, 2021 | by Richard Scheinin

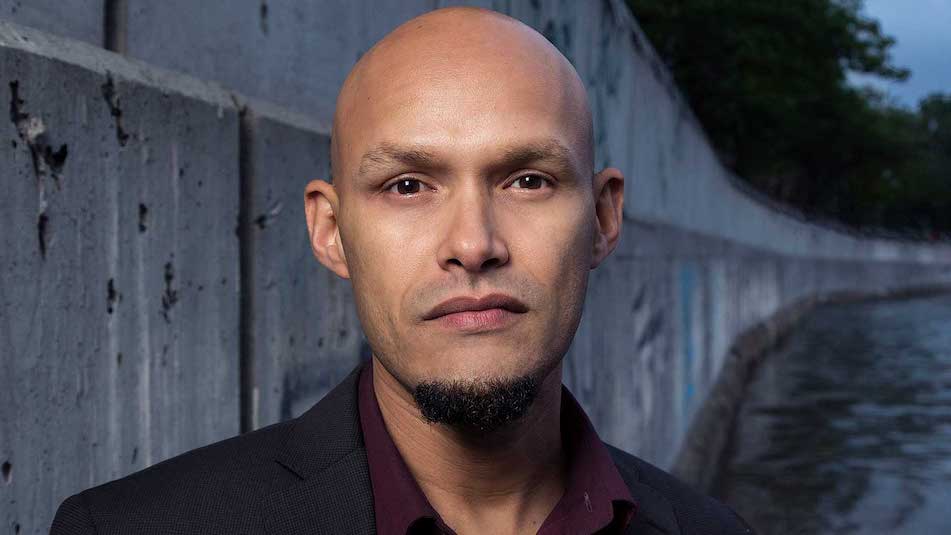

Miguel Zenón

In the second in a series of Q&A posts, SFJAZZ Staff Writer Richard Scheinin speaks to saxophonist Miguel Zenón, Music Director of the NEA Jazz Masters Online Tribute Concert. (A co-production with SFJAZZ, the show streams on April 22.) Last week, Scheinin posted this conversation with drummer Terri Lyne Carrington, one of the new NEA Jazz Masters. In the coming weeks, he will post conversations with the other three members of the 2021 class of NEA Jazz Masters: drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath, saxophonist/composer Henry Threadgill, and radio deejay and historian Phil Schaap.

Saxophonist Miguel Zenón is equal parts passion and precision. If you’ve seen him perform, you know his impact: When his improvised solos get moving, he rocks back on his heels and the notes go flying, like blizzards of diamonds. He’s also a hard-core romantic: The saxophonist enjoys coloring the ends of phrases with vibrato, making them blossom and throb. The effect is ravishing.

Miguel Zenón with his quartet, Achava Jazz Awards, 2019

Raised in Puerto Rico, Zenón, 44, has been a New Yorker for more than 20 years now. A 2008 MacArthur “Genius” award winner, he’s been scooped up at one time or another by many of jazz’s most creative bandleaders: bassist Charlie Haden, conguero Ray Barretto, pianist Fred Hersch, pianist/composer Guillermo Klein, and saxophonist David Sánchez. He has led his own superb quartet since 1999, building a repertory that merges his Caribbean folkloric roots with modern jazz devices. He also spent 15 years as a member of the SFJAZZ Collective, where his wheels-inside-wheels arrangements and original compositions earned him quite a reputation. Warren Wolf, the SFJAZZ Collective’s longtime vibraphonist, has described Zenón as a “mad scientist, a musical genius. It’s like he’s cooking something up, putting some kind of potion together in a bowl and seeing what comes out. And out come these masterpieces.”

SFJAZZ Collective in 2015. (L–R): Robin Eubanks, Matt Penman, Obed Calvaire, Edward Simon, Warren Wolf, Miguel Zenón, Sean Jones, David Sánchez (photo by Jay Blakesberg)

Given his track record, Zenón’s appointment as Music Director of the 2021 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert is a no-brainer. A veteran who knows the international jazz scene, he put together a high-level house band for the project, featuring saxophonist Joe Lovano, trumpeter Avishai Cohen and drummer Obed Calvaire (all friends from his SFJAZZ Collective days), along with bassist Linda May Han Oh and pianist David Virelles. He arranged guest spots for pianist Danilo Pérez (one of his mentors) and master conguero Pedrito Martinez, and he signed up three wondrous singers: Dee Dee Bridgewater (who doubles as the show’s co-host), Dianne Reeves, and Lizz Wright.

When you tune into the April 22 broadcast, you will watch these stars perform Zenón’s arrangements of compositions by 2021 NEA Jazz Masters Terri Lyne Carrington and Tootie Heath. Filmed in January and February, the performances crackle, even though they were painstakingly assembled using remote recording technologies — and even though the show’s performers were dispersed across three continents. The pandemic-related logistical problems forced Zenón to give himself a crash course in remote recording techniques — exploring the various apps and software platforms that have gained currency in the past year, and creating click tracks and MIDI mockups of his arrangements for the musicians to play along with. As you will observe when you watch the broadcast, each musician recorded in isolation, yet the music is not only coherent — it has a vibe; it sounds and feels like jazz.

I called Zenón to talk about the arrangements, the many challenges, and — most importantly — about the four new NEA Jazz Masters: Carrington, Heath, saxophonist/composer Henry Threadgill, and radio deejay and historian Phil Schaap. Supervising the musical aspect of the show has been an intense learning experience for Zenón; it’s given him a whole new bag of production tools. But he can’t wait to get back to live performances once the pandemic recedes: “Those first couple of gigs I have with my band are going to be special. It’s going to be like, “Wow. Look! This is who we are. After so long, we’re able to do this again!”

Q: In the old days — before the pandemic — I imagine your band would get together a few minutes before the gig. You’d sit down, catch up, joke around, and establish a rapport that would then feed into the performance. Recording remotely, you don’t exactly have that.

A: Nope! (laughs)

Q: Is there anything you can do to take the place of that?

A: There’s no substitute. That’s one of the main things that’s really missing from the music (for the NEA show). If we were doing this live, the music would sound totally different. That’s the reality. As good as it sounds, as good as we played it, it would sound totally different if people were actually spending time with each other — really playing it next to each other, you know?

Having said that, I communicated beforehand with everybody in the band. It wasn’t like all I did was send them an email. I talked to Obed. I talked to Pedrito over the phone about how we could work things out, musically speaking. So there was some rapport, at least from a distance.

Pedrito Martinez

Q: In terms of your creative process, do you see any positives coming out of this remote recording process — anything you might carry over into a live performance?

A: Creatively, no. Because you’re really putting this music together — it’s kind of like a puzzle; you already know the way it’s going to be put together. And as I’m writing the arrangements, I’m thinking about that. For example, you can’t have a lot of spots where there’s a shift in tempo — things that you can do live, because you can look at each other and get visual cues. You can’t do anything like that here.

But from a production standpoint, I’ve learned so much — and not only in this project, but all through this past year. Because I’ve had to do so many of these kinds of things, basically playing around with these sound puzzles and editing and things like that. To be honest, I had very little knowledge of that before all this happened. So that’s definitely a tool that I’ve developed.

Q: You just mentioned the visual or physical cues that musicians pick up on while playing together on stage. Obviously, that’s missing when you’re playing remotely. But does it make you develop a second set of antennae — maybe it forces you to listen even harder than you might while on stage?

A: I wouldn’t necessarily compare this to playing live. This is closer to a studio situation, a studio recording. And many of us have been doing a lot of that, where someone sends a track and says, “Can you lay down a solo here?” Or, “Can you lay down a bar here?”

There’s an added sense of focus for the way your part fits with everything else. Because it’s almost like you’re walking into this situation that’s already there — but maybe not all the layers are quite in place yet, so you have to imagine certain things. You think to yourself, “OK, I can do that better. Let me try that again.” In many ways you have a lot more control than if it was being played live. I mean, when it’s live, you just play it.

So it’s a different type of focus. You say, “OK, let me record this bar over here,” and then you can skip ahead to the next spot where you have to play, and you focus on that. It’s just a different scenario.

Q: I’ve seen the completed musical segments for the NEA show and you look extremely focused, Miguel. I can see it in your eyes.

A: Well, you’re laying something down that’s going to fit with everyone else’s part. But you’re not hearing them play! I had all these lines with Avishai (Cohen) and with Joe (Lovano) — but I’m not hearing them play. I don’t know how they’re going to phrase something. So in many ways, I’m really just trying to put all my effort on playing my part as good as possible — as clean as possible. So once it’s time for them to play, and once we’re ready to put all the recorded parts together, it’s going to be easier.

Let’s say I were playing next to Joe on a stage, or next to Avishai, and I could just hear the way they’re phrasing something — if they’re laying something back or articulating something in a certain way. I can hear that and respond to it. Whereas in this remote situation, it wasn’t like that.

So it definitely required a lot more focus on my part, specifically, in order to just lay it down as good as possible.

Avishai Cohen and the SFJAZZ Collective play Charles Mingus' "Goodbye Porkpie Hat"

Q: The people you picked for the band, like Joe and Avishai, are musicians whose playing you know very well — you’ve performed together for years. So as you were recording remotely — laying down your own part — you could at least try to imagine how they might be playing their lines.

A: Of course. And it’s the same with all the musicians in this band — you can kind of imagine it. Also, when you’re writing music, it’s a lot easier when you know who’s going to play it. If I write something that might be a little more difficult for another trumpeter — well, if I’ve got Avishai in the band, I’m thinking, “This is going to be fine.” And if I’m writing for Joe or David or Obed or Linda, I’m thinking, “OK, this is going to be in their zone. This is something they’d enjoy doing” or that would come natural to them.

Q: When did you start working on the NEA Jazz Masters project?

A: They reached out and we started talking about it in the fall. I basically wrote the arrangements late last year, and then we started sending it out to the musicians and figuring out logistics for recording.

Q: Step by step, what else did you do as Music Director?

A: That was just the tip of the iceberg. I think Linda was in Australia when she recorded. I was in New York. Obed was somewhere in Jersey, as was Pedrito. Roman was in Spain. David was in Switzerland. The band was all over the place. Avishai was in Israel. Joe was up in the Hudson Valley. So I had to coordinate everyone: Where would they be? When would they record? What would they record? What instruments were going to be available for them, and what kind of microphones?

And once the tracks were recorded, I did a lot of editing before we began the mixing. And I did a bit of that myself, too.

Another thing is, we had several vocalists. So I had to coordinate with them in terms of the key that was comfortable for them to sing.

Nat "King" Cole performs Charlie Chaplin's "Smile".

Q: You had three vocalists for Charlie Chaplin’s “Smile,” which closes the show. You had Dee Dee Bridgewater, Lizz Wright, and Dianne Reeves. Did you have to negotiate with all three of them to settle on the key?

A: (laughs) I mainly talked to Dee Dee about the key. I figured if it was cool for her, it was cool for everyone. And once we figured out the key, and once we figured out the general vibe we were going after, the rest fell into place. I knew who was in the band, so I was just writing with them in mind.

I think the biggest challenge was just trying to find a spot for everyone, so everyone would be featured and get a spotlight moment.

Q: Toward the end of “Smile,” the singers and the whole band start riffing — it almost feels ad-libbed. But it must have been pre-planned. How did you create that sense of spontaneity?

A: That was intentional. I knew that “Smile” was going to be the closer, and we wanted it to have a happy feel — a joyous type of vibe. And at the end of the song, the idea was to create a platform where it wasn’t very complex — just basing it on this groove, on this vamp, and I felt, “They can just riff on that.” And I let them know: “When you get to this spot near the end, it’s basically like `you got it.’ You can do whatever you want.”

Q: It’s interesting that you can create that sense of jazz coming alive in the moment — despite all the advance planning. There’s some kind of intrinsic contradiction there, but you managed to overcome it.

A: Yeah, like I said, the closest thing I would relate it to is going into a studio and having more of a focused energy about putting something down on tape, instead of just, “Let’s play live, and let’s go for it.” And still, everyone played it great, but it was more of a focus on the task at hand. It’s a different mentality, doing it this way. I don’t necessarily feel it’s better or worse, it’s just different. It’s a different dynamic.

Q: Were you surprised when they asked you to be Music Director? How did that feel?

A: I was so honored. And they put so much effort into having it be a quality show — visually, musically. In every way, it has to be of the highest quality. So I’m just glad to be involved.

Q: Let’s talk about the four inductees. How would you characterize Henry Threadgill’s music?

A: I’ve been hearing it for so long. His music has such an undeniable personal quality to it, in terms of his composing — and his sound! When you hear his sound, you can’t mistake it for anyone else. I’m just glad that us youngish musicians get to be around someone like Henry. He’s a master of his craft.

Henry Threadgill and Make a Move at Umbria Jazz Festival, 1996.

Q: Will you describe the music by Threadgill that viewers will hear on the show, and how it came together? His piece “When Coconuts Fall” is played by a trio: David Virelles (piano), Roman Filiu (alto saxophone), and Lawrence Hoffman (cello).

A: I talked to Henry a bunch about it, and he was very clear about what he wanted. He said, “This is the tune I want, and these are the people I want to play it.”

Q: Just to be clear: You helped plan the segment, but your arranging skills weren’t needed here.

A: Right. Henry has a language of his own, and those three musicians have been working with him for years. So they knew the piece well, and they knew what Henry wanted. In terms of the logistics, it was the hardest part of the show to put together — what with David being in Switzerland and Roman in Spain and Lawrence in New York. But musically, it was the easiest to put together.

Q: How so?

A: We considered several ways of recording it — using different apps or software that would let them play together through the computer in real time. But in the end, we figured the best way was for David to lay down his part first and then have the other guys respond to his part, and that’s how we recorded it… The piece is not in any strict tempo; it’s basically all sort of rubato. But David said, “Let me do this. I’m going to lay it down and make it very clear, so when they hear it, they’ll be able to recognize what’s happening and play their parts.” It worked out perfectly.

Q: You arranged a medley of pieces by Terri Lyne Carrington, another of this year’s honorees. Before we get to that: Have you and Terri ever played together, and can you describe her drumming?

A: I don’t think we’ve ever played together. But, of course, I know her drumming; Terri is an incredible musician. I think the first time I ever heard Terri play live was in Boston. I happened to be there and I noticed that there was going to be this show at Symphony Hall. It was honoring Wayne Shorter. So Wayne was going to be there with his quartet. And (trumpeter) Dave Douglas was there for this project he has with Joe Lovano, playing Wayne’s music. And then there was a trio with (pianist) Geri Allen, (bassist) Esperanza Spalding, and Terri Lyne. And it was a great night, all of it. But I was blown away by Terri. I thought, “Man, she is so amazing.”

Geri Allen, Esperanza Spalding, Terri Lyne Carrington perform Wayne Shorter's "Masqualero" at SFJAZZ

Q: What qualities of her drumming stood out for you?

A: It was everything you look for. There was a lot of control within fluidity. That’s the way I would describe it. She was really in control over everything — all the details. Everything that she was playing was so clear, but at the same time, so relaxed, fluid. That’s kind of what stayed away with me that night, was her playing.

Q: You and the band play several of her tunes on the NEA show: “Waiting Game,” “Insomniac” and “Pray the Gay Away.” Did you go through her albums and pick three compositions that you wanted to arrange?

A: No, she picked those tunes. I talked to her over the phone and told her, “Let me know if you have something specific that you want me to do.” Because I know she has a bunch of projects. And she actually sent me a sound clip where she spliced the original versions of those tunes in order, and she told me, “This is kind of the way I hear it. This is the arc that I’m hearing.” And I was able to just follow her roadmap. With very little variation, I followed what she told me, and then I just orchestrated it, re-harmonized it, and played around with it.

She was very specific. Same thing with Pedrito (Martinez). There’s a section of Terri’s tune (“Pray the Gay Away”) where he plays all these different percussion instruments. That was actually her idea. She said, “I’d like this section to be with percussion.” She didn’t specify Pedrito. But I decided on this groove — a kind of bata groove that I know well — and I thought, “This has to be Pedrito.” And it was so natural when he did it. He just made it in half an hour.

Q: How did the recording process work with Tootie Heath’s tunes?

A: Tootie mentioned one of his compositions that he had recorded recently with (pianist) Emmet Cohen, titled “For Seven’s Sake. And he also pointed out this Kwanza album that he recorded with his siblings (Jimmy Heath and Percy Heath) back in the ‘70s. And I basically just listened to that and picked one of the tunes, “Tafadhali.” And so I decided to create a little medley with those two tunes.

Albert "Tootie" Heath: "Tafadhali" (1973)

Q: I love that Kwanza album. What appealed to you about “Tafadhali”?

A: He had a groovy kind of rootsy thing that a lot of the other music we were doing didn’t have. So I just thought it would be nice to use. And I heard something for Joe in it; I thought it would be a nice vehicle for Joe.

Q: Give me your impressions of Tootie’s drumming. He’s on a million records — with Coltrane, J.J. Johnson, Nina Simone.

A: Modern Jazz Quartet. Sonny Rollins. All kinds of things. At some time in the past decade, I even heard him in his trio with (pianist) Ethan Iverson and (bassist) Ben Street. And it was so cool, because obviously it was different generations. And it was so great to see him digging in and going for it — all that passion, like the special person that he is.

Q: Phil Schaap is another of this year’s Jazz Masters. Do you know him from the radio?

A: Of course. He has a show here in New York (on WKCR) that’s made him a legendary voice — especially with Charlie Parker lovers, like me. He’s such an icon and so respected.

Q: On the NEA show, Wynton Marsalis leads a band that plays one of Phil’s favorite tunes, “Topsy,” the Count Basie number, composed by Eddie Durham. Were you involved with producing that segment?

A: They basically just ran that one by me: “Here’s Wynton.” I said, “Sure.” I think it sounds great.

Count Basie: "Topsy" (1937)

Q: Let’s re-cap. What’s lost and what’s gained in this world of remote recording?

A: The positive thing is that you can put a lot more effort and a lot more detail into the production aspect.

The down side is everything that you miss about playing live. Not just from playing with other musicians, but from playing in front of an audience and feeding off that energy — which is something that many musicians, including myself, took for granted until we got to this situation we’re in now. It really influences the music. It does — even if you don’t want it to. Even if you have some people sitting there in silence, just breathing. Knowing for a fact that you’re playing for someone that’s sitting in front of you, instead of miles away, seeing it over the computer — it influences the way you play. And that’s just what it is.

Q: If the pandemic ends and you get back to playing in the clubs, how do you imagine your experiences of the past year will affect your performances?

A: It’s hard to say until we start playing for real. During the past year, I’ve had a couple of opportunities to play with other musicians live in the same room — with other human beings! And when I’ve had those opportunities, there’s been a certain — it’s almost like an enhanced awareness of what you’re experiencing. It’s like you walk into a situation, which you used to do pretty much every day, and now you just get this once in a while. And you’re like, “Oh, man, it’s really happening.” It’s almost like you want to take it all in at once, and you’re feeding off the situation. And I think that’s what’s going to happen when people start going out and playing in clubs and playing in festivals. Those first couple of gigs are going to be special! (laughs). Those first couple of gigs I have with my band are going to be special. It’s going to be like, “Wow. Look! This is who we are. After so long, we’re able to do this again!”

Watch the 2021 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert online Thursday, April 22, 2021 at 5 PM PT (8 PM ET) from arts.gov and sfjazz.org. This is a free event.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.