"The Sleeping Bear" Awakens: The Revival of the Hammond B-3 Organ

August 14, 2018 | by Richard Scheinin

Jimmy Smith Root Down album artwork (1972)

Just a kid in the early 1960s, Ronnie Foster would hang out at the neighborhood jazz clubs in Buffalo, N.Y., his hometown. Foster had started on the piano when he was 4 and on the organ when he was 11. When he was 12, he learned that Jimmy Smith – the Charlie Parker of the organ – was about to play at a local club, the Royal Arms. Foster figured out where Smith was staying, called him at his motel room, and arranged to have a lesson at the club: “I met him after school, at 3 p.m.,” Foster recalls. “I met all the great organists. I used to sit on the organ bench next to Jack McDuff when he was in town.” This was at another club, the Pine Grill: “I’d sit there and take it all in, and sometimes Jack would just sit there holding an F-sharp nine chord and his drummer, Joe Dukes, would go crazy. So this one time, Jack said to me, `Hold this chord!’ I put my fingers where Jack’s fingers had been, and held the F-sharp nine. And Jack went down to the bar, had a drink, and he was waving to me the whole time. I had to be 13, 14 years old.”

Foster was hooked on the Hammond B-3 organ: “The thing’s got all these stops, the drawer bars. It’s got that rack of foot pedals. The technology fascinated me. But the sound is what moved me. It still moves me today,” says Foster, who began recording for Blue Note Records when he was 21 and – building on what he learned from Jimmy Smith, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jimmy McGriff and his other heroes – came to epitomize the soul-jazz organ sound of the 1970s. He was among the headliners that came to SFJAZZ for a B-3 Organ Festival that also included such royalty as Joey DeFrancesco, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Chester Thompson and Reuben Wilson. In addition, the festival featured several newcomers who are helping shape the organ’s renaissance: Cory Henry (formerly of Snarky Puppy, now with his own Funk Apostles), Lionel “L.j.” Holoman (performing with saxophonist Howard Wiley’s Extra Nappy) and Tammy Hall (a superb pianist who just lately has returned to her organ roots). With two organ combos on each program, the week “covers the full spectrum of styles in terms of lineage – you might say the genealogy of this instrument in jazz,” says Pete Fallico, the longtime Bay Area radio host and B-3 historian who will emcee the shows. “And if anyone in the audience has not previously experienced the sound of the organ – they’ll feel the power of it. Because when an organist locks in with a drummer, when they’re really in sync, that energy is like a locomotive. There’s nothing like the sound of the B-3.”

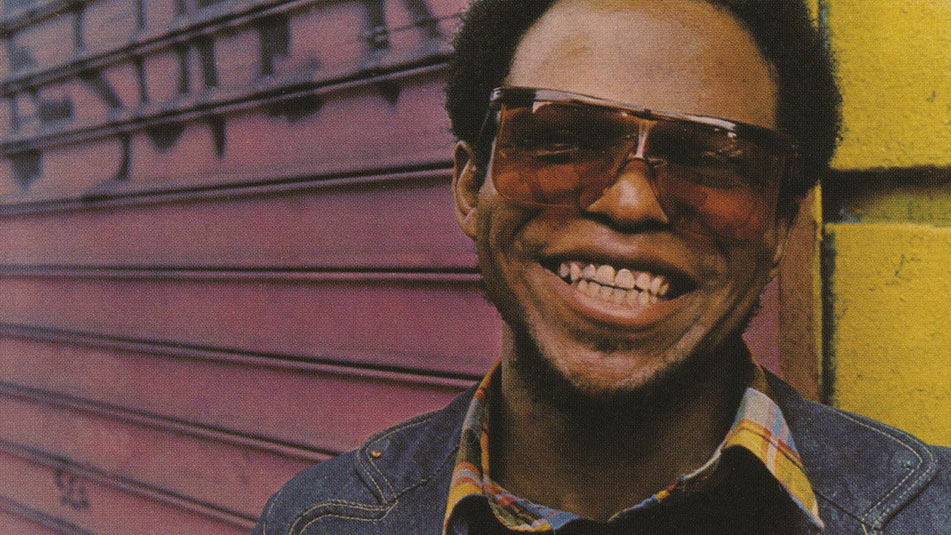

Ronnie Foster On The Avenue album artwork

It’s the sound of Jimmy Smith’s “The Sermon” and Santana’s “Soul Sacrifice” – a familiar sound, even to listeners who haven’t actually seen a B-3 organ. It is an unwieldy instrument, a piece of furniture, really, as big as a casket – and in the 1950s and ‘60s, professional organists were known to drive used hearses from gig to gig, because they were just the right size to carry a 425-pound Hammond B-3 organ. They also were large enough to handle every B-3’s companion: a giant Leslie speaker, housed in its own cabinet and weighing an additional 200 pounds.

Why bother with all this?

Because the instrument is so uniquely expressive: “It’s just a very – no pun intended – a very organic sound,” says Joey DeFrancesco, who sparked the current renaissance 30 years ago when, still a teenager, he was hired by Miles Davis and signed by Columbia Records. Speaking to this writer in 2014, he described the Hammond’s sound like this: “It’s percussive, but it’s very mellow, too. It’s very pristine, crisp – but it can growl. It can do anything. It’s the extension of the person playing it. There are a lot of human elements going on there. And you almost feel like it’s an orchestra, a whole orchestra that you’ve got there.”

Joey DeFrancesco peforming with Van Morrison at SFJAZZ in 2017

Invented by Laurens Hammond – a clockmaker, who also invented card shufflers and 3-D glasses – the B-3 is an electromagnetic machine. The organ contains 91 “tone wheels” that spin past magnetized rods, generating an electric current. The organist adjusts the volume of pitches and the strength of special effects – vibrato and the throbbing “chorus” setting – by manipulating banks of metal sliders, known as “stops” or drawbars. He or she plays bass lines, too, by “kicking” at the foot pedals.

The organ’s percussion feature adds overtones to sustained notes and chords; one can imagine the impact of McDuff’s performance as he held onto that F-sharp nine chord at the Pine Grill. In the hands of a skilled player, the organ can build to an intensity that reverberates inside a listener’s bones – and when the organist pushes the Leslie speaker’s 40-watt amp into overdrive, that’s when the Hammond’s signature “growl” emerges.

The organ can plead and it can preach: “When you talk about jazz organ, you can’t separate it from the church – can’t separate it from its roots,” says Tammy Hall, who grew up playing the organ at Baptist churches in Texas. She remembers how “on a Sunday afternoon, all these different choirs from the different churches would meet at one church and the music would go on until 7 or 8 at night.” She mentions some of the hymns and spirituals for which she was accompanist: “`Amazing Grace.’ `Mary Don’t You Weep.’ `I Know the Lord Will Make a Way,’ and that song could go on for 15 or 20 minutes, because the spirit touches people, chorus after chorus. I still bring all that with me when I’m at the organ.”

Tammy Hall

Having largely made her reputation as a pianist, she is drawing close to the organ once again – a friend actually gave her a B-3 this year – but confesses that it poses challenges. “It is a completely different animal,” she says. “You can hurt yourself if you try to play the organ like you play a piano. Because I tend to play fairly percussively and the organ doesn’t absorb the energy the same way a piano does, and you have to learn how to crawl along the keys.”

Bottom line, she says this about the B-3: “It is a groove machine.”

The first Hammond organ, the Model A, was introduced in 1934; Fats Waller purchased one for his apartment in Manhattan. In 1955, the B-3 emerged; it caught Jimmy Smith’s attention and the revolution began: “He was the innovator to let everybody know what kind of stuff you can do on this instrument,” DeFrancesco said in the 2014 interview. He outlined what Smith did “with the bass line, with the left hand, with the accenting with the left foot – whatever it was, plus playing in different styles, like the Erroll Garner style on the organ, or playing single-note lines. The different sounds that he got – it was amazing, especially in the early days.”

DeFrancesco, who became Smith’s protégé and friend, continued with his history lesson: “And after that, you have Jimmy McGriff. He was more out of the church, a lot of `shout’ sort of stuff. There was still a jazz element, but he had a little something else that made you want to start dancing. So he came out of Jimmy Smith – well, we all do. I do. We all learn stuff and try to go to another level.”

Each of the SFJAZZ headliners has roots in the church, in the blues – and in Jimmy Smith – and each has gone on to fashion a signature voice on the instrument.

Reuben Wilson emerged during the late-1960s boogaloo craze – trumpeter Lee Morgan was on one of his early Blue Note LPs – and remains closely aligned with Smith’s jazz-groove style. Dr. Lonnie Smith is a master of voicings and advanced harmonies. His soloing style is funky and theatrical, filled with extreme dynamics – pin-drop pianissimos and thunderous fortes. Chester Thompson grew up on Jimmy Smith albums, memorizing solos off “The Sermon,” note for note. At the same time, he developed a unique heel-toe pedaling technique, coming up with a funky, double-stuttering bass-line style that he utilized during his decade with Tower of Power and his quarter-century with Santana. (He isn’t on “Soul Sacrifice,” though he is on “Supernatural.”) Ronnie Foster was a particular favorite of Smith’s. The master’s language is right there inside Foster’s playing, though listeners often associate him with the infectious, pop-leaning grooves that drew him into the orbits of Stevie Wonder and George Benson. He recorded with both.

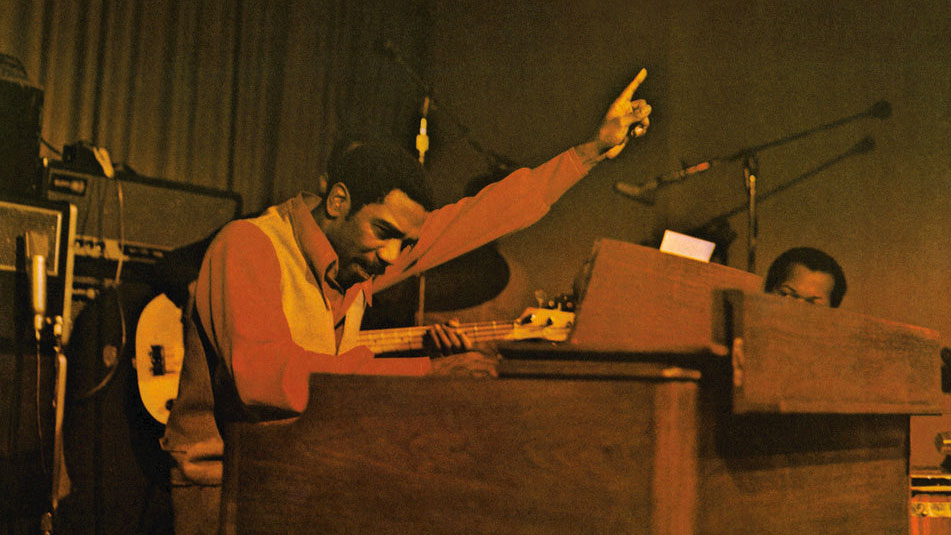

Jimmy Smith performing at SFJAZZ's 11th Street Block Party at the 1995 San Francisco Jazz Festival

By the time DeFrancesco came on the scene in the 1980s, many of the B-3’s established players had been pushed “behind the curtain,” Fallico remembers. The music industry was no longer promoting them. Tastes had changed. “But Joey, with his burst of energy, brought back the Hammond organ and the Leslie speaker to their prominence. He revived the sleeping bear.”

These days, DeFrancesco says in a recent interview, “You could do a whole year of these organ things, like they’re doing at SFJAZZ. Because there’s a million new players.” The show he hosts on Sirius XM radio – he calls it “Organized” – has made him “stay on top of it. The new-school guys have really upped the ante in terms of their abilities – what they’re able to play and the sounds they get.”

Saxophonist Howard Wiley, who performed twice at the festival – with Thompson’s band and with his own Extra Nappy – counts the East Bay’s L.j. Holoman among those new-school players: “He is a beast upon beasts. It was almost shocking at our first rehearsal; every little thing I was doing, he was on it. I was like, `Wow! Who are you?’”

L.j. Holoman performing at S.F.'s Madrone Art Bar with Howard Wiley & Extra Nappy

As Wiley hears it, Holoman isn’t someone who’s made a point of copying this or that player in an academic way: “He’s not like that. You hear that he’s listened to Jimmy Smith, that he’s studied some stride, and that he grew up in the church, of course. But it’s just a very organic thing. You listen to him and you say, `Oh, man, that’s a natural sound. That’s a natural development…’ L.j. really connects with people; he understands that thing – that intangible something.”

Wiley hears similar authenticity in Cory Henry, who came to prominence with Snarky Puppy, the virtuoso jam band, and now leads his own group, the Funk Apostles: “I know Cory has a band full of church boys, just like I do,” Wiley says. With the Funk Apostles, Henry covers Bee Gees and James Brown tunes, while referencing Prince and George Clinton grooves – he moves far outside the B-3’s traditional jazz realm. “But you hear the commitment,” says Wiley. “When you hear Jimmy Smith, you hear the sound of the culture. Same thing with Cory – you hear the culture. You hear the jazz, the church, the blues. You haven’t heard this much excitement around a new player – since who?” he asks rhetorically. “You take Snarky Puppy with Cory, and Snarky Puppy without Cory and it’s two different bands. That’s not saying anything against Snarky Puppy. That’s just how big his energy and his sound is; Cory is just that powerful.”

Cory Henry commanding the stage with Snarky Puppy at SFJAZZ in 2014

At SFJAZZ, Henry focused on the B-3 organ, though he may supplement his performance with bendy synthesizers and other keyboards. In 2018, many B-3 players are doing the same. A whole new generation of B-3 “clones” has come to market in recent years – digital instruments that draw closer and closer to the vintage B-3 sound and sometimes have advantages. Portability, for instance: “I could FedEx my organ,” says DeFrancesco, who plays a clone known as the Viscount Legend. “I love my B-3s with a passion, but I try to get whatever music I can out of whatever organ I’m playing.”

Foster concurs. If a room has a dead acoustic, he can conveniently brighten the sound with a clone. He feels that “the bass on the clone is a little more solid, stronger.” And in the event of a breakdown, it’s easier to get replacement parts for a clone; the Hammond Organ Company stopped producing the B-3 in 1975.

“So the clones are great,” Foster says. “But you know what? You can have reproductions all over the world, but when you sit and play a grand piano – it’s a grand piano, a different experience. And when I sit down at the B-3, it’s a B-3. I’m at home.”

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.