"People want to be moved"

Celebrating the vision of Randall Kline

May 1, 2023 | by Richard Scheinin

Randall Kline at the SFJAZZ Center under construction, 2012. (photo by Michael Short)

On your next visit to the SFJAZZ Center, look around.

Take a moment to marvel at the intimate, one-of-a-kind concert space. The late Ahmad Jamal, among the foremost pianists in the century-long history of jazz, called it “a jewel, a monumental tribute to the power of this music.” The great vocalist Mary Stallings, who sang with Count Basie and Dizzy Gillespie, likens performing on its stage to “standing in a cloud where I’m surrounded by peaceful energy that resonates from my toes to the top of my head.” There’s just something about the room. It’s state-of-the-art, for sure. But more than that, it is a “temple of jazz” (a phrase coined by Cuban pianist Omar Sosa) and it is largely the doing of one individual: Randall Kline, who co-founded SFJAZZ in 1983. Back then, it was a scruffy little community festival. But step by step, over 40 years, he grew that fledgling two-day event into a San Francisco cultural institution and one of the most influential jazz organizations in the world.

That’s why he is being given the SFJAZZ Lifetime Achievement Award at this year’s SFJAZZ Gala, on May 4, with an all-start concert featuring Herbie Hancock (a previous SFJAZZ Lifetime Achievement Award recipient), Rosanne Cash, Ravi Coltrane, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Branford Marsalis and others, hosted by Dianne Reeves (you can watch the livestream here).

Like last year’s winner, Wynton Marsalis, Kline is an evangelizer for jazz, a Johnny Appleseed on behalf of the music, planting seeds to make it grow. The hall began as just that — a seed, an idea. It was Kline’s idea, and he was warned by many that his dream of building the $64 million hall would turn into a fool’s errand. But he put together a world-class team led by architect Mark Cavagnero, an innovator who enjoys talking about John Coltrane’s lifelong pursuit of beauty. Cavagnero was supported by theater designer Len Auerbach, the founder and principal of one the world’s most respected theater consultancy firms; and by acoustician Sam Berkow, who created the acoustic design for Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York. (He also did some work for the Grateful Dead.)

This is perhaps Kline’s greatest talent, his secret sauce — the ability to find the right people for the job at hand, people who share his passion and vision. They become a team—unstoppable. In this case, they created the “temple of jazz.” Since opening 10 years ago, the SFJAZZ Center has become home to a thriving community of artists and music lovers — more than two million people have passed through its doors. They’re still coming, nearly 250,000 every year. They come for jazz. They come for community. They come for inspiration, to be uplifted by the music. They come for the more than 400 concerts presented annually, and for the music education programs that nurture new generations of listeners. In November, when Kline turns 70 and steps down from his job as Executive Artistic Director, SFJAZZ will be ready for the next 40 years, and beyond. That has been his intent from the start — that the organization should outlast him, that it should be here for the long haul. Thanks to Kline, it is a business that embodies the very qualities of the music it serves and the city it calls home: a spirit of discovery, an improvisational edge. It responds to the times, always.

When the SFJAZZ Center went dark three years ago because of the pandemic, Kline oversaw the launch of an entire new digital wing for the organization — something new and compelling that also made business sense by opening up an untapped stream of revenue. The new “Fridays at Five” weekly concert stream maintained SFJAZZ’s vital role as a jazz presenter, helped maintain a member base of 10,000, and led to the recruiting of thousands more worldwide. Kline shrugs it off: “It was like responding to an unexpected change in tempo or key,” he explains.

Gonzalo Rubalcaba performing at SFJAZZ. He is one of the 2023 Gala performers honoring Randall Kline.

He talks like a musician, right? Well, he grew up near Boston in a house where music was revered. His father was an amateur jazz pianist who idolized Erroll Garner and Thelonious Monk. His mother loved pop tunes, show tunes, and opera. Kline — fixated on the latest 45s and LPs from the Beatles and the Stones — picked up the electric bass at age 13. Music became his refuge, an obsession, so it’s no surprise that eventually he set plans to become a professional musician.

In 1974, he moved to San Diego, where he briefly lived with his brother while firming up plans to enroll in the U.C. San Diego jazz program. But a Thanksgiving visit to San Francisco would change his mind—and his future. From his first sight of the San Francisco skyline from the Bay Bridge (“It was like Oz!”), he fell in love with the City by the Bay. Before long, he had relocated to San Francisco, landing a series of entry-level jobs — first as bike messenger, then as backstage security guard — at the Boarding House, the night club on Bush Street that would serve as a stepping-stone to stardom for many up-and-coming artists of the day. He couldn’t help noticing the range of shows at the Boarding House: comedians Steve Martin, Robin Williams, and Lily Tomlin all performed there, as did musicians as stylistically diverse as Bob Marley, Willie Nelson, Patti Smith, Tom Waits, the Meters, and Al Jarreau. Kline also got to see Herbie Hancock and Stan Getz and was bitten by the jazz bug—and jazz would become his raison d’être, his greatest passion. All that eclecticism was a good thing, he decided, and he tucked that lesson away.

Soon he enrolled at the College of Marin, majoring in music while playing “casuals” as a bassist — weddings and bar mitzvahs — but real jazz gigs, too, zipping from one to the next in his ’66 Volkswagen Bug with a rebuilt engine. He rebuilt it, because he was a can-do guy — but he was just getting by. Still, music wasn’t paying the bills, so he took a day gig shelving fruit and vegetables at an organic grocery store in Marin.

Randall Kline, Del Anderson Handy, John Handy. 1/31/19. (photo by Scott Chernis)

Where exactly was this headed?

Luckily for all of us, Kline was an observer. At the Boarding House, he recalls, he had “noticed that Steve Martin’s manager recorded every one of Steve’s shows. Afterwards, they would listen together and refine the act. Talented people worked hard.” The same was true of the head bartender, a guy named Terry Dowling, who became one of Kline’s models “for doing a job right. He was pure Zen while running his crew — imperturbable and tough. Tough but nice. He worked with flair; the way he whisked glasses off a high shelf, with a flourish, was a thing of beauty.”

Here was another lesson: that a team of passionate, hardworking individuals could make all the difference. The staff at the Boarding House did everything correctly: They greeted customers when they walked in. They treated artists with respect. Of course, Kline couldn’t help noticing the flip side of the operation: the club was consistently in financial straits, with payroll often late. But what if a music operation could lock in the business fundamentals while also serving the art?

Young and idealistic, Kline decided to try his hand as a music presenter. He knew someone who might help: Clint Gilbert, the sound and light guy at the Boarding House, who “was working with good but not great sound and lighting systems. But watching Clint, I got to see how someone could get the most out of the limited resources he had. The lighting always looked beautiful and creative. The sound was excellent.”

In 1981, with Gilbert in charge of lighting and sound, Kline put on his first jazz shows — at the Gold Rush, an urban cowboy bar in San Jose. As always, he presented the best: Dexter Gordon, Kenny Burrell, Jack DeJohnette, Flora Purim and Airto. But business models for jazz were changing; clubs were folding, audiences were iffy, the whole musical landscape was in flux. Kline lost $10,000 on his Monday night series — a fortune for a kid who’d been shelving vegetables not too long before.

But he kept plugging away.

Kary Schulman, an acquaintance of Gilbert’s who ran the city’s Hotel Tax Fund/Grants for the Arts program, encouraged him and Gilbert to investigate the non-profit business model that was emerging in the arts world. They ended up receiving a $10,000 grant from the Hotel Tax Fund, as well as another $10,000 grant from the San Francisco Foundation. (Its arts program officer sat on the Hotel Tax Fund’s board, saw Kline and Gilbert’s application, and invited the young partners to apply for SFF funding.)

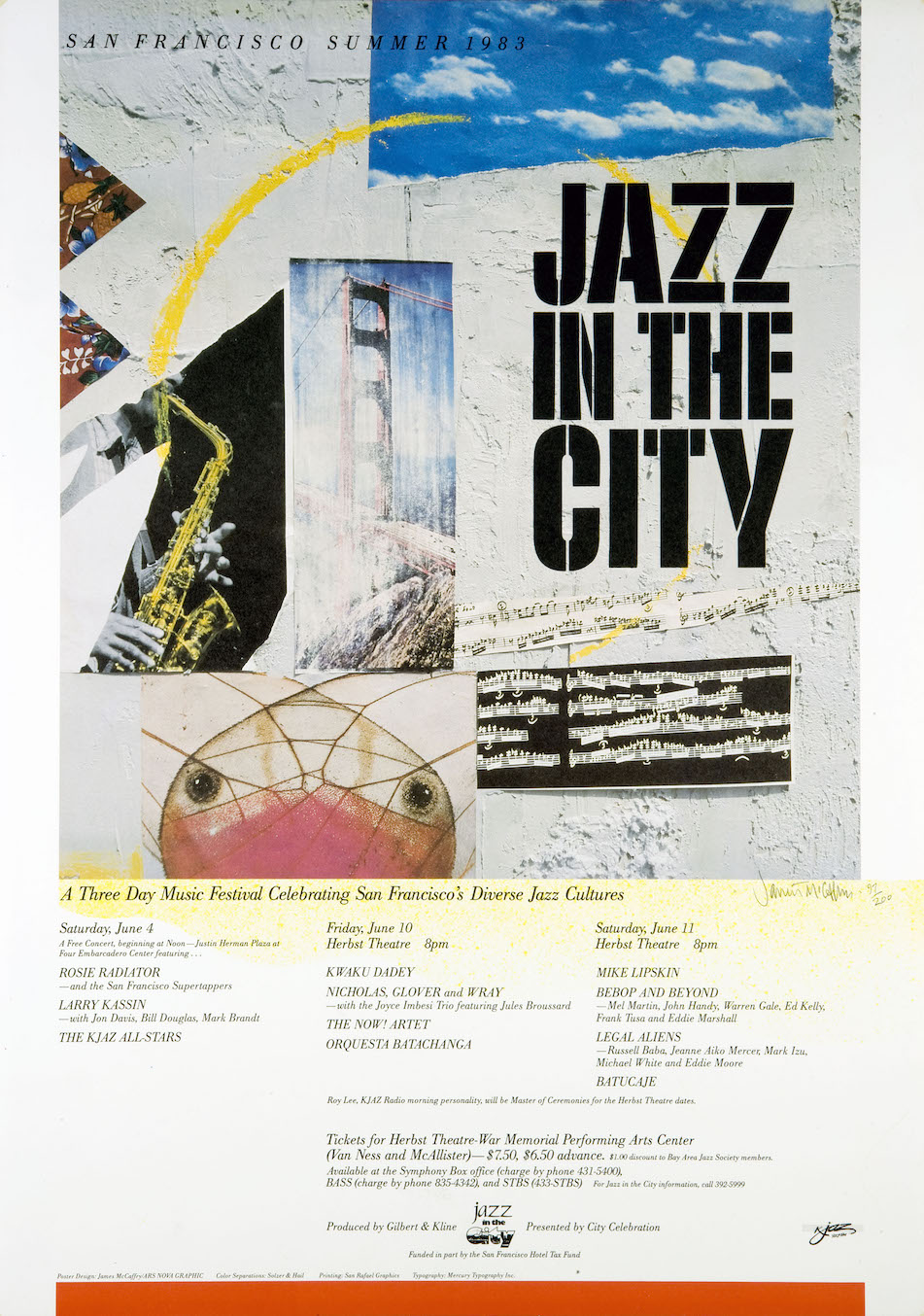

They parlayed this start-up sum into the first Jazz in the City Festival, in 1983. It flopped: There was way too much variety onstage at the Herbst Theatre: bebop, along with stride piano, tap dancers, a charanga dance orchestra, a 1930s-style vocal trio, and an avant-garde blowout band. It was a mishmash. Instead of being “all things to all people,” the shows wound up being “no things to no people.” Attendance was lousy, but again, Kline didn’t give up.

That inaugural festival — the beginnings of what would grow into SFJAZZ — became an invaluable lesson in learning from mistakes, and improvising. Kline and Gilbert went back to their funders, including Schulman, who was impressed with their vision and commitment to jazz — and to solid business practices. (They insisted on a repayment plan for the first season’s losses.) Fortified with a new round of funding, they staged their second festival in 1984. This one was a financial and artistic success. Kline had discovered that audiences responded to thematic programming: a night of bebop, a night of blues, a night of bossa nova. This, too, became part of his secret sauce as San Francisco’s new jazz organization grew.

During its first few years, the festival drew exclusively on Bay Area talent. There was a wealth of it: legends like Joe Henderson, Bobby Hutcherson, and Tony Williams lived here. As did Don Cherry, John Handy, Mary Stallings, Armando Peraza, Anthony Braxton, and many others — including a saxophone prodigy named Joshua Redman who, at age 15, participated in the festival’s first Youth in Jazz program.

In 1988, the festival rolled the dice and presented a big-budget, star-studded show drawing for the first time on national talent: a Stride Piano Summit. It sold out. In 1989, a Jazz Tap Summit pulled out the stops once again — and was another sell-out. It included the Nicholas Brothers, stars of the Swing Era, who had scored a Hollywood hit with their gravity-defying “Jumpin’ Jive” dance routine alongside Cab Calloway in the film Stormy Weather in 1943. Now, Kline paired them with a 15-year-old newcomer named Savion Glover, who described his tap style as “young and funk.”

This festival thought outside the box — and San Francisco’s eclectic and open-minded audiences responded.

Kline observes that the organization progressed in decadelong phases. Throughout the 1980s, it rode an unprecedented wave of recognition for jazz. Wynton Marsalis was spreading his message that jazz was “America’s classical music.” The National Endowment for the Arts joined the campaign to treat jazz — this great, yet under-recognized African American art form — as high art, deserving a place alongside opera and symphonic music. During this period, Kline emerged as an important missionary for the music he loves. He was studying the music industry from the ground up, while running his own publicity and artist management firm — soaking up arcane information about ad copy, fonts, and graphic design. (He will still gladly talk your ear off about all of this.) Ultimately, this side operation became too time consuming, so he set it aside to focus on his growing jazz endeavor, which benefited from all the lessons he’d learned in the trenches. (His partner, Clint Gilbert, soon stepped away from the jazz operation to pursue his own sound and lighting business, leaving Kline as sole leader.)

In 1990, the organization’s signature event took a new name — the San Francisco Jazz Festival — and pushed on with its out-of-the-box shows. In the spring of 1991, it presented the posthumous world premiere of Charles Mingus’s orchestral magnum opus Epitaph, as well as a solo piano recital by the astonishing avant-gardist Cecil Taylor at Grace Cathedral. Looking back, Kline thinks this was some of the festival’s best programming to date — certainly its most ambitious — but attendance wasn’t consistent and the organization ran a deficit.

Cecil Taylor at Grace Cathedral, 6/17/91. (photo by Gerry Waitz)

What to do?

“We rolled the dice one more time,” he says, eliminating spring programming and consolidating the 1992 festival into a 17-day autumn extravaganza at rented venues around the Bay. Kline often talks about taking “well-considered risks,” like a poker player who understands the playing field and recognizes when the time is right for a bold move.

This was one of those moments — and he had the backing of his staff, an impassioned team who referred to themselves as “The Jazz Warriors.” The decision to consolidate shows actually had the effect of expanding programming, he points out, and the bet paid off: 52,000 people packed 22 events, including a show by Tony Bennett, an all-star tribute to John Coltrane, and an Indo-jazz-fusion experiment with saxophonist John Handy, sarod master Ali Akbar Khan, and tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain.

This set the stage for a decade of growth, and the nation took notice. The San Francisco Jazz Festival was “the crown jewel of American jazz festivals,” declared the Chicago Tribune, calling it “unrivaled as the most intelligently programmed and creatively staged jazz soirée in the nation." By the end of the ’90s, the festival was presenting nearly 100 shows annually, including expanded performances by and for young people. A cultural powerhouse with a $3 million budget, it attracted funding from all quarters: city, state and federal agencies, foundations, corporations, and private donors. A new business model for jazz had arrived — and “this little festival that could barely hold its pants up the first year,” Kline says, proudly, “was pushing the art form forward.”

Building on that momentum, the festival began its third decade by turning itself into a year-round presenter and rebranding itself as the San Francisco Jazz Organization — SFJAZZ for short. In 2000, it established a Spring Season, co-curated by Kline and Joshua Redman, who was named artistic director for this new months-long block of shows. In 2001, Redman gave the second Spring Season a title: “Tradition in Transition.” That neatly summarized what SFJAZZ was about: honoring the roots of jazz while exploring the way ahead. The organization cemented its commitment to jazz education by founding the SFJAZZ High School All-Stars and establishing a dedicated Education Department, expanding public school educational offerings in the process.

In 2004, it founded the SFJAZZ Collective, an all-star resident octet whose original members included Redman and the great vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson. The band was given a dual mission: Its members were commissioned to compose brand-new tunes for the Collective and to re-interpret classic jazz compositions by giants like Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, and Thelonious Monk. “By moving music forward and celebrating jazz as a dynamic tradition, the Collective embodies SFJAZZ’s organizational principles,” Kline declared.

The dynamism characterized SFJAZZ’s eclectic programming throughout the decade — everything from avant-gardist David Murray (who grew up in the East Bay) to bossa nova genius João Gilberto, sitar master Ravi Shankar, singer-songwriter Rosanne Cash, and groundbreaking pianist and harpist Alice Coltrane, whose Masonic Auditorium concert in 2006 was her final public performance.

While other arts groups fell by the wayside as the economy tottered in the late oughts, SFJAZZ secured a way ahead. By the end of the decade, it had 3,000 members. Today it has nearly 18,000. Its success is grounded in unwavering values: presenting great musicians, giving audiences exceptional listening experiences, and taking those well-considered risks while hewing to the bottom line. “SFJAZZ is a business,” says Kline, emphatically. “This soulful and noble art form can’t find its way to a sizable and growing audience unless it’s delivered by a sturdy business vehicle — unless we treat our passion as a business.”

Stepping on stage to introduce an act, he gauges the temperature of the audience. Does it thirst for “the transcendent moment” that he, as a longtime fan, has come to crave? “How do you set the stage for that moment?” he once asked. “For some reason, I’m fascinated by that question. I still hold onto this very naive belief — and I think it’s a human nature thing — that fundamentally people want to be moved, to be totally transported by the music. There’s something in it that makes us better. It’s this gathering-of-the-tribe thing around something that can move you — I don’t know if ‘spiritually’ is the right word, but emotionally. So why am I in this? I’m trying to figure it out: How do you set it up for the musician and the audience, to make that moment happen?”

He made sure the SFJAZZ Center was designed to help make it happen: great sound, unobstructed sight lines. Ground was broken in 2011, the hall opened in 2013, and here we are — 40 years into the SFJAZZ journey, sitting in this crown jewel of the art form. It’s like a church or basilica, with the stage at its center — an altar, with the musicians as high priests and the audience encircling them, a jazz congregation.

Every detail has been considered; Kline loves the fact that every seat in the house has its own cupholder: “Strictly as a fan, sitting there with a little bourbon in my glass, I’m comfortable in my seat — any seat,” he says. The hall is his baby: “I like to move around, get all the different perspectives. And I often close my eyes and have that visceral experience of being wrapped inside this music, and I can experience this under the best conditions. And when I open my eyes, I see a lot of other people, a whole community that’s zeroed in on this thing — they’re experiencing this excellence, this mastery on stage. And I hear the sound, the beautiful acoustics, and I think, like, ‘Wow, where else can I do this?’”

Randall Kline presenting the SFJAZZ LIfetime Achievement Award to Mavis Staples. 1/30/20.

(photo by Scott Chernis)

The answer is, “Nowhere else.” The space is unique. SFJAZZ is unique. It’s a community, a tribe of music lovers. Many of the high priests of the music will gather to honor Kline at this year’s Gala. They understand the magic of the hall. It’s a place where we can all gather around the campfire, so to speak, and have the primal experience of being lifted up by live music. Do that year after year, and you build a self-perpetuating energy field that makes this hall the place to be. It all comes from honoring the art — and from the vision of one man. Thank you, Randall Kline, for guiding us through these first 40 years. SFJAZZ wouldn’t exist without you; it’s as simple as that.

And now, look out! Here comes the fifth decade of SFJAZZ….