The Leonard Bernstein Jazz Connection

February 9, 2018 | by Rusty Aceves

"Jazz is the ultimate common denominator of the American musical style."

— Leonard Bernstein

For decades, jazz has been described as “America’s classical music” — a well-meaning if controversial and largely inadequate phrase often attributed to writer Russell Roth that attempts to “legitimize” an art form that has never required an elevated, “high art” comparison to stand on its own. In fact, jazz's uniquely democratic and inclusive expression of collective, spontaneous creation stood decidedly in opposition to the formalized strictures of so-called "classical" music. Regardless, for 20th century American composers writing for the symphony hall or opera stage, even those working within the formalized “classical music” establishment, jazz was an inescapable influence, and none had so fully embraced that influence as composer and longtime conductor of the New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein. And in return, Bernstein has provided the jazz world with a rich trove of indelible compositions to explore and use a basis for improvisation. As SFJAZZ and Opera Parallele team up to present a world premiere production of Bernstein's classic jazz-influenced opera Trouble In Tahiti paired with Bay Area composer Jake Heggie's opera At The Statue of Venus at SFJAZZ on February 14-18, we look back at the many jazz connections to Leonard Bernstein.

Bernstein was immersed in jazz from his youth, working as a jazz pianist in his teenage years and directing a swing band at a summer camp. His 1939 undergraduate thesis at Harvard, “The Absorption of Race Elements into American Music,” argued that jazz is at the foundation of all American composition, and his initial post-graduate employment included transcribing jazz for a music publisher, exposing the young composer to the inner workings of the improviser’s art.

In 1944, Bernstein was a 25-year-old up-and-comer immersed in jazz when he composed the score for Jerome Robbins’ ballet Fancy Free, and wrote the prologue tune “Big Stuff” specifically for Billie Holiday, though he didn’t present it to her for fear that his youth, inexperience, and minimal finances would prevent him from securing a star of her caliber. Bernstein’s concerns were unfounded, as Holiday did eventually record the song with the Toots Camarata Orchestra seven months after Fancy Free premiered, and ultimately recorded it seven total times, including a version for the 1946 Decca score recording. Inspired by the concept of Fancy Free and debuting on Broadway the same year, Bernstein’s musical collaboration with lyricists Comden and Green resulted in one of his most enduring hits, 1944’s On the Town. The story of three sailors on liberty contained a number of memorable songs that were eagerly adapted by jazz musicians as part of the “standards” book that is still in use today, and two of them, “Some Other Time” and “Lucky to Be Me,” became signature tunes in the repertoire of piano great Bill Evans.

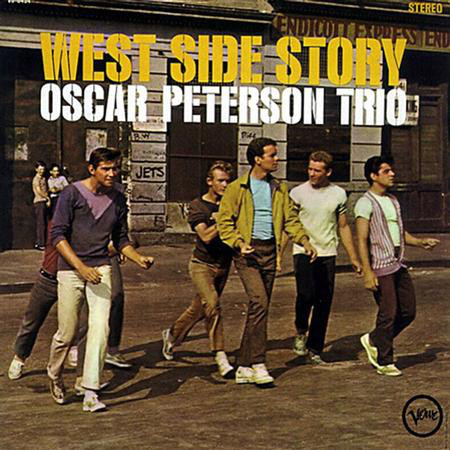

Originally commissioned for clarinetist Woody Herman and his Thundering Herd big band (who didn’t actually perform it), Bernstein’s score for clarinet solo and jazz ensemble, Prelude, Fugue and Riffs (1949), was premiered by Benny Goodman on the educational television program Omnibus, and a movement of the composer’s Symphony No. 2: The Age of Anxiety from the same year was written for solo jazz piano and percussion. 1952’s one-act opera Trouble in Tahiti contained a running “Greek chorus” commentary provided by a harmonizing vocal trio (referred to as a "Jazz Trio" in the score) that suggested the Modernaires or the Pied Pipers. All of these works, each inspired by jazz or incorporating elements of it, led to what is arguably Bernstein’s most enduring triumph as a Broadway composer.  The score to 1957’s Broadway smash West Side Story is a gift that keeps on giving to jazz artists, with Dave Brubeck, Oscar Peterson, Cal Tjader, Stan Kenton, David Liebman, and André Previn all recording albums dedicated to jazz interpretations of the musical’s immortal songs. Individual tunes including “Maria,” “Cool,” “Somewhere,” and “I Feel Pretty” have earned a place in jazz’s standards songbook, with Sarah Vaughan, Arturo Sandoval, Branford Marsalis, Marian McPartland, and Maynard Ferguson all recording versions of “Maria” alone. Drummer and bandleader Buddy Rich recorded a medley of West Side Story songs by arranger Bill Reddie for his 1966 album Swingin’ New Big Band and used the arrangement as a crowd-pleasing concert closer for two decades until his death in 1987.

The score to 1957’s Broadway smash West Side Story is a gift that keeps on giving to jazz artists, with Dave Brubeck, Oscar Peterson, Cal Tjader, Stan Kenton, David Liebman, and André Previn all recording albums dedicated to jazz interpretations of the musical’s immortal songs. Individual tunes including “Maria,” “Cool,” “Somewhere,” and “I Feel Pretty” have earned a place in jazz’s standards songbook, with Sarah Vaughan, Arturo Sandoval, Branford Marsalis, Marian McPartland, and Maynard Ferguson all recording versions of “Maria” alone. Drummer and bandleader Buddy Rich recorded a medley of West Side Story songs by arranger Bill Reddie for his 1966 album Swingin’ New Big Band and used the arrangement as a crowd-pleasing concert closer for two decades until his death in 1987.

Pianists, in particular, seem to have a special affinity for Bernstein’s work. In addition to the West Side Story albums by Peterson, Brubeck, Kenton, and Previn, hard bop piano great Tommy Flanagan devoted his 1960 Blue Note trio session Lonely Town to music from On the Town, West Side Story, Candide (1956), and Wonderful Town (1953). More recently, pianist Bill Charlap put his own stamp on Bernstein, recording 2004’s Somewhere: The Songs of Leonard Bernstein.

There have, of course, been other encounters between the composer and major jazz artists. One one memorable occasion in 1956, Bernstein conducted a performance of "St. Louis Blues" with Louis Armstrong at New York City College's Lewisohn Stadium in the presence of the song's composer, W.C. Handy.

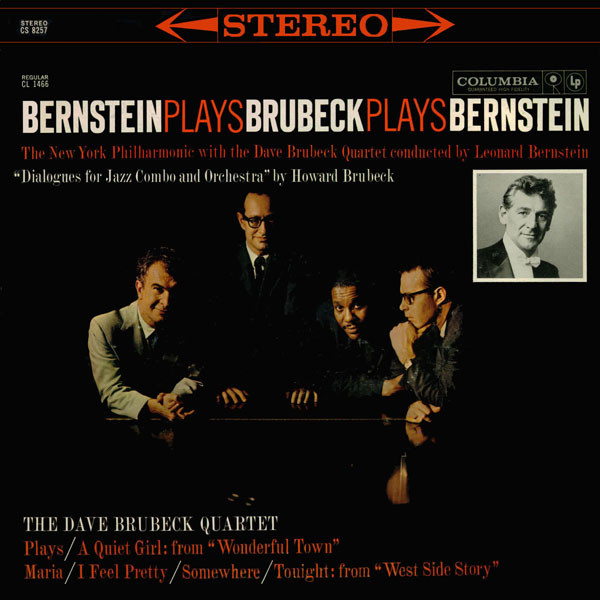

The adaptations and collaborations have been many, but one of the most successful blends of jazz with the work of Leonard Bernstein is surely the 1961 Columbia album Bernstein plays Brubeck plays Bernstein, which brings together the creative life of Bernstein as composer and conductor of the New York Philharmonic in collaboration with pianist Dave Brubeck’s legendary quartet. The program consists of four pieces from West Side Story, “A Quiet Girl” from Wonderful Town, and the four-part Dialogues for Jazz Combo and Orchestra composed by Brubeck’s older brother Howard Brubeck, all featuring the Dave Brubeck Quartet and the New York Philharmonic under the baton of Bernstein. The album is a perfect expression of how jazz informed Bernstein’s compositional approach during his career, and the lasting impression his work had on the jazz artists who followed him.

the 1961 Columbia album Bernstein plays Brubeck plays Bernstein, which brings together the creative life of Bernstein as composer and conductor of the New York Philharmonic in collaboration with pianist Dave Brubeck’s legendary quartet. The program consists of four pieces from West Side Story, “A Quiet Girl” from Wonderful Town, and the four-part Dialogues for Jazz Combo and Orchestra composed by Brubeck’s older brother Howard Brubeck, all featuring the Dave Brubeck Quartet and the New York Philharmonic under the baton of Bernstein. The album is a perfect expression of how jazz informed Bernstein’s compositional approach during his career, and the lasting impression his work had on the jazz artists who followed him.