A Century Of Song: Monk At 100

September 25, 2017 | By Richard Scheinin

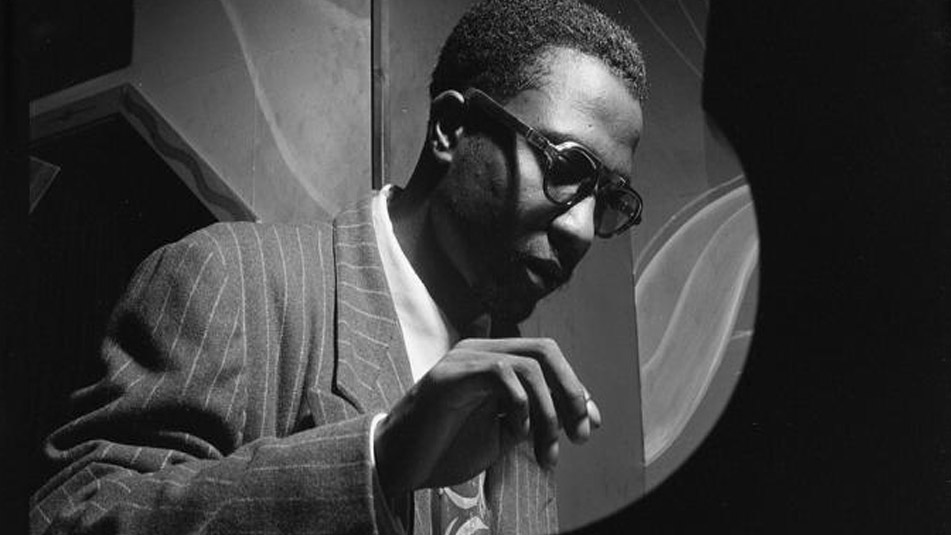

Thelonious Monk (Photo by William Gottlieb)

Pianist Jason Moran is 42 years old and has been listening to Thelonious Monk’s music since he was 13, when Monk became “an addiction, an obsession, a fixation.” It happened fast. A hip-hop fanatic, he was “a kid going through puberty and I was always searching for how I could be different from my friends. Luckily, Monk grabbed my ear,” Moran says. “His songs held out their hand to me.”

Moran starts singing some of the tunes: “Little Rootie Tootie” with its bumpety-bump train rhythms, and then “Four in One,” with its whirling corkscrew of a melody — somehow still intensely sing-able. As he demonstrates, Moran breaks into laughter.

“But there was so much more to digest than just his music,” he goes on. “What also grabbed my attention were his style and his aesthetic — his beard and his goatee and his album covers. There was his whole persona — how he danced at the piano, how he lay his hands on the keys and attacked a note. How did he do that?”

Monk became a template for something beyond Monk, a model for making art that matters. And as SFJAZZ celebrates the 100th anniversary of Monk’s birth with a series of October concerts, Moran will join in, showing why it is that Monk’s music remains open and fresh, radical and relevant, continually lending itself to reinvention.

Born Oct. 10, 1917, Monk made music that invites you in, and then teases you with its mystery. How did he do that? How did he create tunes that are instantly sing-able — children “get” Monk — yet operate as the purest distillations of mood and emotion: the joy, the bounce, the freedom, the struggle and pain. Monk was “reckoning with the tension and pressure that America puts on people of color,” Moran says.

He is still investigating the “how” of it — and still responding to the flow of Monk’s phrasing, his “addiction to rhythm and how he played that rhythm, more like a drum.” It’s why hip-hop producers sample Monk: they like his hooks, they go for what Moran calls “his lope — the way a person walks, a gait. Sometimes if I listen to his songs, I move my neck in the same way I would if I were listening to Wu-Tang Clan.”

Four Monk interpreters will lead the centenary series, starting with pianist Danilo Perez and his trio (Oct. 13). They will re-explore Perez’s Panamonk album from 1996, demonstrating the snug fit between Monk’s rhythmic pulse and Afro-Cuban clave: “Monk embodies the dance,” says Perez who grew up in Panama. “He is the father. He is the key to the Afro-American sound.”

Next comes Moran (Oct. 14), bringing back In My Mind: Monk at Town Hall, a co-commission from SFJAZZ that uses a mini-big band and multi-media to reimagine Monk’s 1959 concert. After a decade of performances — In My Mind premiered in 2007 — it has “a bit of a patina on it,” says Moran, who wants the evening to carry a sense of history, of Monk’s roots. It will include an audio tape of Monk talking, pacing the wooden floor of the Manhattan loft where he rehearsed for the Town Hall concert — and breaking into a tap dance that spells out the melody to “Little Rootie Tootie,” a composition inspired by the trains Monk watched as a child in North Carolina.

Pianist-arranger John Beasley and his 16-piece MONK’estra (Oct. 15) will delve into their new album (MONK’estra, Volume 2), which extends Monk’s tunes to include rap and Gil Evans-like atmospherics. It zeros in on some of those hooky Monk riffs: One of Beasley’s tricks is to extract a signature riff from a Monk tune and have the band stretch out over it, spinning variations on the riff — and dropping all of that on top of, say, a slow hip-hop groove.

Finally, the SFJAZZ Collective (two concerts on Oct. 28, including a family matinee) will dust off some of the arrangements from its 2007 album of Monk tunes. The recording includes an arrangement by saxophonist Miguel Zenon of “San Francisco Holiday” that is memorable, setting Monk’s melody over a buoyant, Puerto Rican bomba bass line and then flipping into a double-time bridge where the band evokes the bustle of traffic in midtown Manhattan. The music surprises, yet feels like Monk, who spent much of his life in New York neighborhoods where Latin music was in the air. As much as his friends Dizzy Gillespie or Charlie Parker, Monk absorbed those sounds.

Each of the artists interviewed for this article broke into song while discussing Monk — there is no resisting those melodies. And there is no getting around the double-challenge presented by Monk’s music: Wanting to understand and penetrate the specific musical language that Monk created, but also — when interpreting his music — stepping away from it enough to create something original.

Monk helps out with the latter challenge, according to Edward Simon, the SFJAZZ Collective’s pianist. He says Monk’s compositions — exercises in concision, often fitting on a single page — contain “a genetic code.” The melody, harmony, rhythm and voice leading have a kind of Bach-like perfection, yet (as does Bach) Monk takes unexpected turns: “He gives you all the raw material you need to come up with a beautiful arrangement or interpretation. If you have the imagination, something special is likely to come out. That’s what I mean by `genetic code’ — his tunes already have a built-in beauty.”

And built-in rhythm: Whether by chance or design, the rhythms of Monk’s melodies have a way of lining up with the clave, the rhythmic pattern that pervades Afro-Cuban music. That would explain why so many of Monk’s tunes have been successfully re-vamped along Afro-Cuban lines, Simon says.

“Look, Monk is super rhythmic,” Beasley agrees, “so it makes sense that he would work on any kind of groove as long as it’s a swinging groove, whether it’s Latin or funk or hip-hop or whatever it is. You take one of his tunes, like `Skippy’ — the 32-bar form has this sort of shout chorus already built in. It sounds very much to me like Jimmy Lunceford, like a riff band.”

It’s been half a century since Beasley discovered Monk’s music — he was nine or ten years old and the tunes were “Nutty” and “Work” — but he sounds as captivated as ever: “His 32-bar or blues-form tunes are chock full of all these little ditties to be expanded upon — almost like classical music where you take a theme and run it through a set of variations. With Monk, you have these little funky riffs, these thematic chunks that you can isolate and stretch out over time,” he says, explaining his arranging trick, “and they still sound like Monk.”

A century after his birth, Monk is still relevant and still a fascination. Monk is different. He is full of paradox. Sean Jones, the trumpeter in the SFJAZZ Collective, remembers how older musicians used to warn him not to get too cocky when performing Monk’s catchy little tunes: “It was like the easiest thing in the world to sing, the hardest thing in the world to play.”

As for Perez, it’s been a couple of decades since he started peeling back the layers of the onion with Monk. First he heard the power of Monk’s swing, and then Monk’s rhythmic connection to New Orleans, Cuba, Haiti and Panama. Monk was tapped into the African source — like something ancient, offering rhythmic possibilities that Perez continues to study.

Monk humbles him, he says.

Sitting by his piano as he talks over the phone, he plays something simple, a B7 chord, letting it ring out as Monk might have, then cutting it off to let one note peek through, just slightly.

He laughs.

“It took me a while to get that,” he says. With Monk, even a B7 chord is an enigma, carrying emotions that “bring a tear to my eye,” Perez says. “He brought the mystery into the music. I really feel like there is this edge of things that he gets to — the unknown, the future. Even if you’ve heard a piece of his music many times, there’s always questions.”

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.