ABDULLAH IBRAHIM

A LIFE IN SONG

October 20, 2023 | by Richard Scheinin

Abdullah Ibrahim performing at SFJAZZ, 5/1/16 (photo by Bill Evans)

With Abdullah Ibrahim performing 11/16-18 with his current trio, we revisit staff writer Richard Scheinin's profile of the South African legend and 2019 NEA Jazz Master.

Abdullah Ibrahim is fond of saying that his songs tell the story of his life — which would make his life a song.

One story told by this venerable pianist and composer is about his most famous song, “Mannenberg,” named after a black township created under apartheid in Cape Town, South Africa, Ibrahim’s hometown. Historically, the city is a crossroads, a musical melting pot, an African New Orleans. And in June 1974, Ibrahim and his band were recording there amid the government’s forced removals of black and “coloured” families of mixed ethnicity. “It was basically a war zone outside,” he says, recalling how he sat down at an upright piano in a corner of the studio and began to compose “Mannenberg,” which would become the unofficial anthem of the anti-apartheid movement — and which sounds absolutely nothing like music from a war zone. It is pure joy, a celebration: proud music, hold-your-head-high music.

Now 89, he laughs at the seeming contradiction and explains one of his guiding principles. It holds “that softness overcomes the hardness. If you look at water, for example, it is nourishing but it can also be forceful, it can erode what is in front of it. So even in that horrendous system that we lived under in South Africa, we learned from our parents and our grandparents and our teachers that softness will overcome.”

Nelson Mandela called Ibrahim — who performed at Mandela’s 1994 presidential inauguration — “our Mozart.” Decades earlier, Duke Ellington claimed him as a protégé and arranged his first recording contract, hearing Ibrahim’s connection to the root. One hears the drum in Ibrahim’s piano playing, just as one does in Ellington’s and just as one does in that most percussive of pianists, Thelonious Monk, a key influence on Ibrahim. He and Monk share a spirit, an essence. Alone at the piano, each seems utterly absorbed with the spaces that open up and just hang there, as if time could go on forever within the confines of a three-minute song.

Nelson Mandela called Ibrahim — who performed at Mandela’s 1994 presidential inauguration — “our Mozart.” Decades earlier, Duke Ellington claimed him as a protégé and arranged his first recording contract, hearing Ibrahim’s connection to the root. One hears the drum in Ibrahim’s piano playing, just as one does in Ellington’s and just as one does in that most percussive of pianists, Thelonious Monk, a key influence on Ibrahim. He and Monk share a spirit, an essence. Alone at the piano, each seems utterly absorbed with the spaces that open up and just hang there, as if time could go on forever within the confines of a three-minute song.

There is a voice-like quality to Ibrahim’s compositions, which are deceptively simple masterpieces of craftsmanship. For instance, “Mannenberg” rides on a riff, a seven-note melody that repeats and repeats, adhering to a relaxed if jaunty rhythm. The melody is the rhythm; the rhythm is the melody. And there’s not a wasted note. Ibrahim is a “less is more” composer, though his compositions somehow feel large, timeless, ancient and new, opening onto vistas: African jazz panoramas from a man who grew up in the constricted spaces of apartheid.

Born in 1934 and baptized Adolph Johannes Brand, he springs — like “Water from an Ancient Well” (the title of one of his most beautiful tunes) — from a musical family. His mother and grandmother were pianists in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and some of his best compositions carry echoes of church hymns. And that’s not all they carry. Because going back to his teen years as a club performer in the Cape Town crossroads, he absorbed so much else: traditional music from much of Africa, along with waltzes and quick-steps, raga and samba, Chinese and Malay music, and the marabi township music that still infiltrates his sound, infectiously melodic and danceable. And of course there was swing and bebop: the black American GIs from whom he bought the latest records nicknamed him “Dollar” Brand, which was how he was known until his conversion to Islam.

Exiled from South Africa in 1962, he met Ellington in Zurich a year later. Moving to New York, he was part of the free jazz scene at its most heavy-duty moment, hanging out with John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor, playing and recording with his soul mate Don Cherry. In 1972, I saw Ibrahim perform with trumpeter Cherry at Coleman’s loft, in a quartet with bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Ed Blackwell. Wow. The music proceeded seamlessly, song to song, like a suite: graceful, melodic, a rising prayer, a holy commotion, then moving toward the universal silence that seems to underlie Ibrahim’s music.

“We practice 50 years, trying to find a technique,” Ibrahim says. “But in the end, it is a process of trying to find the silence… Monk, Coltrane and Bird, they all had this. Well, you practice and practice and practice and then you forget about it.” A student of Japanese martial arts for half a century, he likens this endpoint to the Zen notion of “no mind. It’s this point of profound silence that you are trying to reach. Or it’s the sound of that silence.”

“We practice 50 years, trying to find a technique,” Ibrahim says. “But in the end, it is a process of trying to find the silence… Monk, Coltrane and Bird, they all had this. Well, you practice and practice and practice and then you forget about it.” A student of Japanese martial arts for half a century, he likens this endpoint to the Zen notion of “no mind. It’s this point of profound silence that you are trying to reach. Or it’s the sound of that silence.”

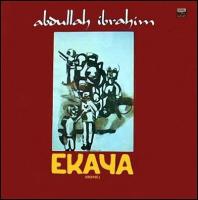

During the 1980s in Manhattan at the club Sweet Basil, Ibrahim often would perform for a week, sometimes for two, with the 7-piece band he calls Ekaya, which means “home.” Almost always, the musicians would go to the well: “Mandela,” “The Wedding,” “Mama,” “African Marketplace” — so many songs, so many stories told. And at the end of a late night set, as the last notes vanished into who-knows-where, the audience would just sit there, stunned to silence by the power of what had just happened.

The cabs were flying by outside on Seventh Avenue South, but all of us had found a sanctuary in the music. We were home.

Abdullah Ibrahim performs with his trio featuring saxophonist Cleve Guyton and bassist Noah Jackson, 11/16-18. Tickets are available here.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.

Originally posted 4/1/16