15 SAXOPHONE ALBUMS

YOU SHOULD HEAR

December 14, 2018 | by Richard Scheinin

John Coltrane A Love Supreme artwork

For the better part of a century, the sound of jazz has been inseparable from the sound of the saxophone: urgent, wailing, uniquely expressive. Again and again, the innovations of saxophonists have carried the music forward: from Lester Young to Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and beyond.

So here we are, attempting to boil down this history of saxophone glory into a list of 15 recordings. Good luck, right? What you are about to read covers about 80 years of jazz history. I’ve tried to include “essential” recordings, ones that anyone interested in jazz should hear. But here and there, the list has tipped toward personal favorites. After all, how can you select just one album by Sonny Rollins? Sometimes you just have to go with the one you love the most.

What’s more, this list of “essentials” is missing dozens of groundbreaking players. That’s inevitable, but it hurts to think of the musicians who didn’t make the cut. There’s no Johnny Hodges on this list. No Ben Webster or Dexter Gordon. No Cannonball Adderley or Joe Henderson or Jackie McLean. No Roland Kirk or Pharoah Sanders or Archie Shepp. No Sam Rivers or Billy Harper. No Michael Brecker or Kenny Garrett or Joe Lovano or Ravi Coltrane.

To a degree, then, the completion of this list requires the making of another. Maybe that will happen a few months from now.

But in the meantime, check out these 15 essentials.

Coleman Hawkins

Body and Soul (RCA, 1939, anthologized on Coleman Hawkins: Ken Burns’ Jazz, on Verve)

As an elder, Hawkins – “Father of the tenor saxophone” – would mentor Thelonious Monk and play with the avant-gardist Eric Dolphy. But this iconic track is from an earlier phase of his career, when he literally was putting the saxophone on the map, demonstrating that it wasn’t some awkward marching band instrument – no, thanks to Hawkins it would become the dominant instrument in jazz. This track showed the way. Like his hero Louis Armstrong, Hawkins’s conception was commanding and brilliantly clear. Listen to his sound, brawny and ripe, as he moves through chorus after chorus, decorating his phrases with florid touches, letting notes trail, then heading back toward the mountaintop. His improvisation unfolds in stages, like a giant cadenza. Hawkins was not only showing his peers how to play a ballad magnificently. More basically, he was teaching them to build an improvised solo on the instrument that would come to define the very sound of jazz.

Lester Young

Indiana (Aladdin, 1942, available on The Complete Aladdin Recordings of Lester Young, on Blue Note)

When does breath become sound? That’s the mystery with Lester Young, who begins his final round of choruses on this track with a barely murmured phrase – just the trace of an idea, though it immediately catches the attention. What’s next, you wonder? Where is Lester taking me? Like Miles Davis, one of his heirs, Young is taking you toward a bright beauty, hiding inside a hazy, bluesy swirl. There are never too many notes with Young. His playing is an essence – floating, silky, swinging. This trio track with pianist Nat King Cole and bassist Red Callender is an insistent foot-tapper. Yet it feels so relaxed that you don’t know whether to dance or simply listen in on the conversation. Is Lester laughing? Is he crying? Inside of a short phrase, he can do both. His voice shaped a generation of players and continues to inspire.

Charlie Parker

Bird of Paradise (Dial, 1947, anthologized on The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, Savoy Jazz)

Like a radio receiver, young Charlie Parker – “Bird” – dialed in Hawkins and Young, along with Chu Berry, Ben Webster and other genius saxophonists working in Kansas City, Parker’s hometown, during the 1930s. What happened next, and why? Well, how do you explain J.S. Bach? Parker’s language, like Bach’s, might have emerged from some universal source, given its internal logic and utter beauty – not to mention its blues essence, crazy-ass melodies and tempos that careen like the subways that sped Parker from Harlem to 52nd Street after his move to New York. He set down some gorgeous ballad performances, too, including “Bird of Paradise” (based on the chord changes to “All the Things You Are”), from his 1946-47 recordings for the Dial label. After you’ve moved through its neighboring tracks – “Dexterity,” “Bongo Bop,” “Klact-oveeseds-tene,” and “Scrapple from the Apple” – you will have established your footing in Bird’s World. All those tunes, by the way, feature his working band of the period with trumpeter Miles Davis and drummer Max Roach.

Sonny Rollins

Sonny Rollins Plus 4 (Prestige, 1956)

The exuberance, the endless spinning out of ideas: Rollins is like no other improviser. This album features two of his best compositions – “Valse Hot” and “Pent-Up House” – and finds him in such ebullient spirits that you can’t help but feel good while listening. Doubly good, in that the album pairs him with the great trumpeter Clifford Brown. They play like soul mates, the empathy heightened by the fact that this is a working band: It’s actually the Clifford Brown-Max Roach Quintet, of which Rollins was a member. Yet track after track, the saxophonist commands the date. Listen to his solo on “Kiss and Run” – buoyant, invincibly swinging, melodiously inventive and, above all, filled with joy and his special brand of vitality. Rollins is unstoppable, like a river. He rounds out the date with “Count Your Blessings,” heartfelt and direct, a real goose-bump performance. Thank you, Mr. Rollins.

Eric Dolphy

Far Cry (New Jazz, 1962)

Oh, Dolphy, nobody made sounds like you: those warbles and wails, those fluttered cooings and exploding guffaws. The virtuoso multi-reedist’s albums are filled with a singular brand of avant-bebop, wild and whimsical. He will crack you up. Here on his tune “Miss Ann,” he sounds like Charlie Parker set across a diagonal: Cubist Bird, strangely logical and never more than a few millimeters from the blues. And could Dolphy ever play a melody: His “Left Alone” (on flute) brings chills. His “Tenderly” (solo, on alto sax) will reduce you to a puddle. His “It’s Magic” (on bass clarinet) has got to be one of the most soulful things you ever will hear, even though he squeaks in the middle of his performance. Dolphy was equal parts intellect, heart and imagination – and obsession, for he was always obsessively chasing his truth, the sound he dreamed inside his head. Coltrane loved him, as did Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman, with whom Dolphy recorded the iconic “Free Jazz” on the same day he recorded this special album, “Far Cry.”

John Coltrane

A Love Supreme (Impulse, 1965)

A landmark in 20th century music, the record begins with the bold swipe of a Chinese gong, its reverberations clearing the air for what’s to come. “A Love Supreme” is a suite that builds like a religious service, and was described by the saxophonist in the LP’s liner notes as an offering to God. It crystalizes the Coltrane sound, that of his supernova saxophone and of his classic quartet with pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. After more than half a century, the album is still breathtaking. Listeners sense that “everything was brand new” for the four musicians around the time of the recording, saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, John’s son, told me a few years back. “It’s like when planets align. It doesn’t happen every day.”

Wayne Shorter

JuJu (Blue Note, 1965)

Now 85 years old, Shorter is the Yoda of jazz, a master of secret harmonic motion and a player whose soloing style has grown increasingly economical and cryptic. But this is from an earlier time, when Shorter – under the spell of his friend Coltrane – was seeking a kind of raging beauty within the forms of his amazing compositions. “Deluge.” “House of Jade.” “Yes or No.” “Twelve More Bars to Go.” The tunes here are unforgettable, and Shorter’s quartet – it’s essentially Coltrane’s, with McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones and bassist Reggie Workman – feels oceanic, feeding raw energy to the saxophonist as his solos move up, up, up in a boiling spiritual ascent. This is one of the best records of the 1960s – hell, of any era. It never gets old.

Stan Getz

Sweet Rain (Verve, 1967)

This exquisite album finds Getz – like Shorter on JuJu – under Coltrane’s sway. But Getz’s temperament creates a very different mood. His tenor sound is startlingly pure and flute-like, light as a feather. Casting an aura of rare elegance, he sounds something like Lester Young in modal clothing. The band – with pianist Chick Corea, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Grady Tate – is perfect. As is the song selection, which ranges from Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “O Grande Amor” to Corea’s “Litha” and “Windows” and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Con Alma.” On the latter, Getz’s solo takes on gradual heat; his coda then moves from a whisper to a wail in a matter of seconds. It’s operatic. Track by track, the performances merge clarity and restraint with barely concealed intensity. Each tune is like a white-hot coal.

Albert Ayler

In Greenwich Village (Impulse, 1967)

At the opposite end of the spectrum from Mr. Getz is Mr. Ayler. This album assembles a bunch of the tenor saxophonist’s ecstatic anthems: “Change Has Come,” “Truth is Marching In,” “Our Prayer.” Each is part parade ground music, part folk song, and part Pentecostal tumult. The performances are massive, overwhelming, and, yes, joyously blaring, led by the imploring saxophonist and the trumpeter Donald Ayler, the leader’s brother. Call it “free jazz” or “fire music” or “the new wave” – what it all means is that Ayler was setting a torch to jazz orthodoxy, much as the MC5 and other punk bands were about to do to rock ‘n’ roll. Ayler was labeled a heretic. But the truth is, every note he played drew from the same streams as jazz, and particularly from the African-American church. This album was recorded live at the Village Vanguard and the Village Theatre, which several years later was given a new name: the Fillmore East.

Ornette Coleman

Science Fiction (Columbia, 1972)

I still get the chills, listening to this album, and I’ve listened to it a thousand times. More than a saxophonist, Coleman was a pure creative artist whose gift for melody and whose bedrock affinity for blues feeling became key elements in a body of work that is unique in American music. Still, as a saxophonist, Coleman is beyond normal greatness. His sound is so deeply human: With every pleading note, he is both old soul and pure child. His late ‘50s recordings inspired a revolution in jazz. Science Fiction announced his second coming. It is a blood-rush of pulsing creative energy and beauty. The quicksilver synchronicity among the musicians is astonishing. Coleman assembled his close friends, all master players, for the date: trumpeters Don Cherry and Bobby Bradford, saxophonist Dewey Redman, bassist Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins. Asha Puthli, from Bombay, sings two of Coleman’s most haunting songs, “What Reason Could I Give” and “All My Life.” Above a swarming beehive of improvised sound and the overdubbed cries of a baby, the poet David Henderson recites the words of the title track: “My… life… belongs… to…. civilization.” Through the healthy use of studio effects – extreme reverb and compression – that track gives the impression of music and words arriving from another time and place. You could say this was Afrofuturism before the term was invented. But really, it was just Ornette doing what he always did: reaching into his own personal dimension, then drawing open the curtain, revealing his world to the rest of us.

Anthony Braxton

New York, Fall 1974 (Arista, 1975, available on The Complete Arista Recordings of Anthony Braxton, on Mosaic Records)

Braxton is as serious a musician as you will ever come across, and he is a gas. On this album, he plays alto saxophone, sopranino saxophone, flute, alto flute, clarinet and contrabass clarinet. He is an investigator of sound, a decrier of category, and he has gone on to compose marathon operas on cosmic themes that never get performed. But here he is in a New York recording studio in 1974, recording for a major label, making clear his jazz roots with his quartet – one of the period’s definitive bands – and some special guests. The album opens with earth-orbiting bebop as the quartet locks into Braxton’s virtuoso puzzle language: post-Charlie Parker, post-Ornette Coleman, post-Eric Dolphy. With each track, comes something different: a fresh-aired chamber piece that references Stravinsky; a relaxed interlude of mid-tempo swing; a brain-teasing duet for Braxton and synthesizer; a dark-hued composition for saxophone quartet featuring Braxton and three other innovators: Oliver Lake, Julius Hemphill and Hamiet Bluiett. The album brings back the intensity and restlessness of the period – and its open-eared attitude, which allowed for the jazz mainstream and avant-garde to mingle for a time. In the decades since, Braxton has become a kind of one-man academy. Scores of musicians have walked through its doors; they are the free thinkers, the crazy people, the ones who keep the surprises coming.

Branford Marsalis

Trio Jeepy (Columbia, 1989)

Marsalis went into the studio and let the tapes roll for this date with drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts, his friend and peer, and bassist Milt “The Judge” Hinton, a revered elder. It’s an album of casual virtuosity and exuberant swing, with Marsalis – 28 at the time of the recording – in Sonny Rollins mode, flooding the changes and making it sound easy. The trio plays Marsalis’s own “Housed from Edward,” then steams through “The Nearness of You,” “Three Little Words,” “Makin’ Whoopee” and Billy Strayhorn’s “U.M.M.G.” The latter is taken at a fast clip with Hinton laying down a groove that almost steals the show. This album is a pleasure. It’s intimate, as if it were recorded in your living room. It bespeaks good feeling and love for the jazz tradition. On several concluding tracks, Delbert Felix steps in on bass as the trio dives into the “modal burnout” style that would become Marsalis’s trademark in the years ahead.

Steve Coleman

Curves of Life (RCA/BMG, 1995)

This live recording at the Hot Brass Club in Paris captures the alto saxophonist at a peak moment with his band the Five Elements. It’s easy to get caught up in descriptions of Coleman’s complex synthesis, which draws heavily from bebop and funk and extracts from the traditional music of Cuba, West Africa and India. Forget about all that. Five Elements is a band that turns on a dime – think James Brown – as Coleman flies over and through the matrix of polyrhythmic funk, reminding you of two Parkers, Charlie and Maceo. A founder in the 1980s of the movement known as M-Base, Coleman’s influence has become Art Blakey-like through the years: Dozens of great players have passed through his groups, absorbing his concepts and process, his way of guiding a band through lightning-quick shifts in tempo, key, density, mood. All those elements get focused, laser-like. You can hear it on “Curves of Life.” The music burns and the audience responds: shouting, screaming. The final track, “I’m Burnin’ Up (Fire Theme),” augments the core band with three rappers and a guest saxophonist, the titanic David Murray, who roars through the proceedings.

Joshua Redman

The Bad Plus Joshua Redman (Nonesuch, 2015)

A collaboration between the saxophonist and the piano trio known as The Bad Plus, this album casts a unified mood: haunting, hypnotic and lovely. Redman is a thinking player, and an adaptable one, always working to elevate a given situation. He works the full range of the horn with an even and beautiful tone here, spinning new melodies through his solos, imperceptibly building tension until the music spills over into high drama and spiritual catharsis. It happens throughout this recording, most notably on “Beauty Has It Hard” (by drummer Dave King) and “Silence is the Question” (by bassist Reid Anderson). Something special was going on when these musicians got together. The long-running trio turned into a quartet; the four musicians sound like a working band. The recording emblemizes a trend in today’s jazz, where collaboration and process often take precedence over a single player's leadership and vision. That said, Redman – 46 when this album was made – deserves a special word. A “name” player since his early 20s, he remains a hardworking musician and a risk-taker, one who keeps expanding his technical chops and expressive abilities. That’s rare, in any era.

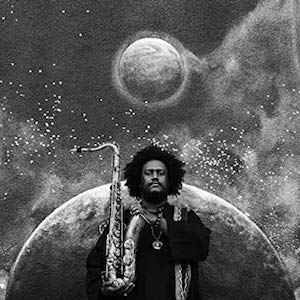

Kamasi Washington

The Epic (Brainfeeder, 2015)

Tenor saxophonist Washington brandishes a storm-the-barricades urgency, Coltrane-like: He can pin you to the wall and push you through to the other side – where you brush off the dust, scratch your head and say, "Man, I didn't know this place existed." The best moments of The Epic are like that, starting with “Change of the Guard,” the anthem that sets off this nearly three-hour, triple-disc suite built around a 10-piece band augmented by orchestra and choir. Across the 17 tracks, one hears Washington’s immersion in the African-American church, in the onward-and-upward sweep of ‘70s soul (Marvin Gaye, Donny Hathaway), and in the spiritualized ‘70s jazz of Alice Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders and Billy Harper. Washington, 34 when The Epic was released, assimilates all of this, while making it feel of the moment. He has a well-known parallel career in hip-hop; he plays on Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly. The loose-knit music collective that has coalesced around him in Los Angeles – known as the West Coast Get Down – seems to be playing the song of the moment in jazz, and Washington is playing the song of songs.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.