A Conversation with AHMAD JAMAL:

The Innovator, Still Moving Forward at 89

August 16, 2019 | by Richard Scheinin

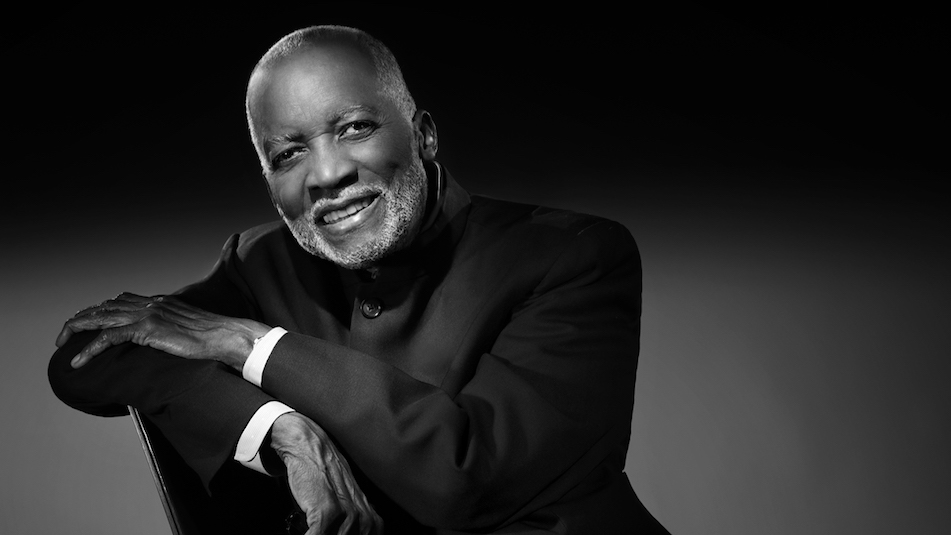

Ahmad Jamal (photo by Harcourt, Paris)

Ahmad Jamal is on the short list of great jazz pianists. He is an innovator and a hit-maker, a pure creative artist.

From the time he emerged in the early 1950s, his sound was different. It was about timbre and touch, and about the “orchestration” of his performances, involving careful changes in tempo and dynamics. There was an architecture to his group’s improvisations: the control of ebb and flow, the tension and release — and the resulting groove. Audiences loved it: In 1958, the pianist’s At the Pershing: But Not for Me LP — including his classic take on “Poinciana” — became a national hit. Miles Davis was a champion, lauding Jamal for his judicious virtuosity — the lightness of his touch, the way he left space around his notes. Jamal was a musician’s musician with a fan club, an insider and a popularizer wrapped into one package. Now 89 years old, he is among the most sampled artists of recent decades. Hip-hop producers love his time, his feel, his hooks — and borrow liberally from his old recordings. “I was just talking to my lawyer about it,” he says. “The problem is, how do you collect?”

We talked to Jamal about all of this — and about his four-night run (Sept. 5-8, 2019) at SFJAZZ, where he and his group will open the 2019-20 season.

Q: What’s the source of your orchestral approach? Where does it come from?

A: Erroll Garner! They don’t come any more orchestrated than Erroll. He’s an orchestra within himself. He was my biggest influence. Art Tatum was a big influence; I met him when I was 14 years old. But Erroll, he was from my hometown, Pittsburgh. He was my hero.

Q: Pittsburgh was a musical hotbed when you were growing up.

A: Pittsburgh is second to none. I came up in a high school — George Westinghouse High School — where Erroll Garner and Dodo Marmarosa also went to school, and so did Mary Lou Williams. Isn’t that something? Billy Strayhorn was from my neighborhood, and there was a little tap dancer known as Gene Kelly who lived nearby; maybe you’ve heard of him. And then there was Mary Cardwell Dawson, my teacher, who started the first African-American opera company. You see, we had an array of talent coming out of Pittsburgh, starting with Earl Hines. But don’t forget about Art Blakey, and later there was George Benson, Stanley Turrentine and his brother Tommy. It goes on and on; I can’t finish the list. That’s where I got all my stuff from. We also had Mr. Johnny Costa, the pianist who was on nationwide television all those years with Mr. Rogers. Johnny never left Pittsburgh; what a phenomenal talent.

Q: Let’s talk more about your orchestral approach. What kinds of ensembles did you play with as a kid?

A: I grew up orchestrally in Pittsburgh. I played with many, many orchestras, so I always maintained an orchestra in my head. That’s why I don’t like to refer to my group as a “trio.” I prefer to call it an “ensemble,” because I’ve played with ensembles all my life. At Westinghouse High, I played in the junior orchestra and the senior orchestra, and our music director, Mr. Carl McVicker, started something called the K-Dets, which was very innovative. It was an All-American orchestra, playing both European classical music and American classical music — ‘jazz’ — in the 1940s.

That’s another thing about Pittsburgh. We didn’t have that separation of church and state: You had to study Beethoven and Bach, Duke Ellington and Art Tatum. You had to study both worlds, the European classical music as well as the American classical music, which some people call ‘jazz.’

Q: You had a rigorous training. Today, when you meet young musicians, what advice do you give them?

A: The advice I didn’t get: Have more than one option. Have more than one exit door. If you have only one exit door, you might get trampled on the way out. So I tell them, the only way to have options is to go to school. And if you can’t get what you want performing-wise, then teach for a while. If you can’t get what you want from teaching, conduct for a while or compose for a while. The person who doesn’t have options is in trouble. I was caught up in a world at 17 years old, and at 17 years old you can’t always make the right choices. You haven’t mastered the philosophy of “yes” and “no.” Those are two magic words, and at 17 years old, you haven’t developed that discernment.

Q: What happened to you at age 17?

A: I’ve been exposed to some real extremes: At 17, you leave home, you don’t know a thing. But I don’t talk about what I missed. I talk about what I have yet to gain…. I’m still learning every day.

Q: Do you ever reflect on your accomplishments — on some of the highlights of your career?

A: I try to not go backwards. I go forward; what’s next? Going backwards is very dangerous. But I’ll mention one thing. In 1952 at Carnegie Hall, Duke Ellington was honored for his 25th year in music. Duke was the star, of course. And there was also Charlie Parker and strings, and Dizzy Gillespie, and Billie Holiday — her first appearance in New York in years because of that stupid cabaret card business — and Stan Getz, and myself. I’m the only living headliner from that night. So, some experiences are unforgettable. That’s one of them.

Q: You were very young at that time, 22 years old. You made your first recordings just one year before that, in 1951. The guitarist Ray Crawford was in your trio — I mean, your ensemble!

A: It’s OK. Everybody says it.

Q: Some of your early recordings hint at hip-hop — the sound and the feel of the music on certain tracks. Sometimes it’s a lot more than a hint, which I guess is why you’ve been sampled so much.

A: Well, Ray Crawford — he had been a tenor saxophonist, one of the premiere saxophonists in the country. But he had lung problems, and he had to stop, and he moved to guitar. And Ray used to get a percussive sound on the frets of his guitar, and that was highly emulated by many, many guitarists — notable guitarists. And we also were monumental in the use of congas some time after that, but the concept you mention — that was derived from Ray getting that percussive effect on the guitar.

Q: From its early days, your group’s arrangements were distinctive.

A: In 1951, I was 21 years old when I took over the group — when I was given the non-enviable job of leadership, and I started writing the charts. All that stuff was written… the arrangements and the improvisation were not accidental. It came from a long background of things I learned in Pittsburgh, and from having some of the best musicians in the world, (bassist) Israel Crosby being one, and Ray Crawford being another one. And that’s before I brought in the drums with Vernel Fournier.

Q: Were you surprised when At the Pershing became a hit?

A: Not only that: It’s one of the most plagiarized and copied recordings in the world. People are still drawing from that. Commercials are being done from that, and rappers and hip-hoppers are still pulling from that.

That’s why I just talked to my lawyer about the hundreds of thousands (of dollars) that’s owed to me. I’m one of the most sampled musicians in the world, which was illustrated in a video by Robert Glasper — you can find it online. Robert Glasper describes the music that has supported hip-hop, through the sampling of musicians such as myself and Herbie Hancock and others.

Did you know that Jay-Z sampled my composition “Pastures”? It’s a monumental string piece, orchestrated by Richard Evans.

Q: Tell me about your four nights at SFJAZZ. Will you play any solo piano?

A: There will be solo work within the ensemble work. And I should tell you: I’m thinking about recording there in San Francisco, because it’s a long time since I stayed in one place like that — playing four nights in the same place. We’ll have a chance to sit down and relax and enjoy what we’re doing as an ensemble. That is unusual for me. I went all the way to the Ukraine — for one concert!

Q: So why are you playing four nights in San Francisco?

A: I don’t do nightclubs anymore. But that hall, it’s not a nightclub. It’s a jewel. (Jamal is referring to the Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the SFJAZZ Center, which opened in 2013.) We should have more of those around the world, and especially in the United States. Yet there’s only two that represent this music. One is in New York — Wynton Marsalis’s place at Lincoln Center — and the other is in San Francisco. In both instances, it’s a monumental tribute to the power of this music. But why are there not others? There should be Louis Armstrong centers and Ella Fitzgerald centers and Sidney Bechet centers throughout the country. This music is very, very important, so I hope other venues will follow suit — more Carnegie Halls built on the strength of this music.

Q: Why are there so few?

A: We have a great civilization in America, but civilization is the ability to move goods from one place to another. Culture is a different thing, and civilization is nothing without culture. It’s quite evident. Just look at what’s happening today in society in the United States.

When I was a kid in 1959, I made a trip to Egypt and Khartoum; those are cultures that have been around for a very long time. But there have been only two cultural contributions in America: American Indian art, which is not promoted, and American classical music — or ‘jazz’ — which also is not promoted. It ends there, and civilization cannot last or advance without culture. We’ve got all these wonderful machines courtesy of Steve Jobs and his associates. But you have the negative effects of these machines, as well — addictive behavior, people crossing the street and not looking at anything around them, and hacking, hacking every day.

Q: Is it a distraction for you? How much composing are you able to do?

A: In this day of electronics — this machine, that machine — there are so many distractions. But I still think in terms of composing every day. I don’t necessarily put everything down, but I compose. I’ve been composing every day of my life. It’s inspiration, every day.

Q: And do you still practice every day?

A: Sometimes I don’t give my music the attention it deserves. But that’s a human failing. Have you read every book in your library? No? Greetings! Welcome to the club.