Keeping the Spirit Alive:

John Hanrahan Plays Wayne Shorter's 'JuJu'

September 16, 2019 | by Richard Scheinin

John Hanrahan

John Hanrahan is 52 years old, and a drummer since he was 11. He has logged thousands of hours on bandstands. He plays in an Allman Brothers cover band, the Freestone Peaches, and he can discourse on the Grateful Dead, a band he has seen perform more than 120 times. He is a talker, a man of many enthusiasms. But asked to identify his most profound inspiration as a musician, he boils his answer down to two words.

Elvin Jones.

“Elvin changed my life,” he says. “He is the innovator — pure innovation. He is the man.”

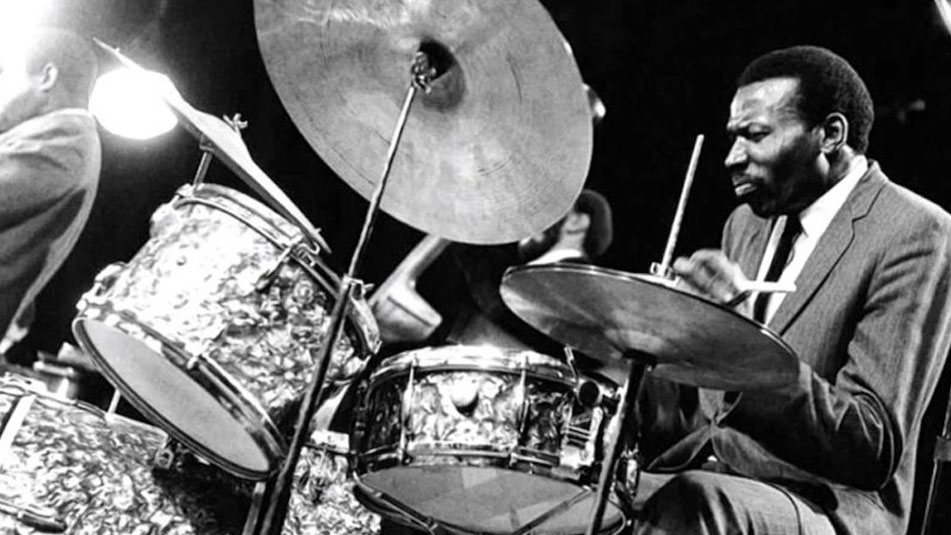

Elvin Jones

Jones was the driving force in saxophonist John Coltrane’s classic quartet of the 1960s. Hanrahan worships that band, and he has made a name for himself over the past few years by performing the music of Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, an album-length suite that builds like a religious service, powerful in its sweep. Recorded by Coltrane on Dec. 9, 1964, A Love Supreme was a landmark event in 20th century music — and a million seller for Impulse! Records. In the liner notes to the LP, the saxophonist described the suite as an offering, “an attempt,” he wrote, “to say `THANK YOU GOD’ through our work.”

Jones was at the center of its ebb and flow, its explosive tension and release, its swirling ascent.

But it wasn’t his best performance, says Hanrahan, who has spent years getting inside Jones’s singular approach to accompaniment and rhythm. (Check out Hanrahan’s A Love Supreme: Live at Kuumbwa Jazz Center.)

No, he says, Jones’s best work can be found on an album recorded four months earlier, on Aug. 3, 1964, under the leadership of a different saxophonist, and under the auspices of a different record label: JuJu by Wayne Shorter, on Blue Note. “It’s perfect,” says Hanrahan, who lives in Santa Cruz. “Everything you’re hearing there is just the epitome of what Elvin does. You’ve got a ballad, a blues, uptempo swing, a 6/8 thing — every aspect of his mastery, every style, is separated out. I don’t know, man. Just the feel of that album and Elvin’s playing — what a genius. Look, I’ll just say it: JuJu is the best recording of Elvin’s drumming.”

Having staked that claim, Hanrahan has set a new challenge for himself: On Sept. 19, leading his own quartet — with saxophonist Andrew Dixon, pianist Dahveed Behroozi and bassist Giulio Xavier Cetto — he will perform the music of JuJu at the Joe Henderson Lab, the club-like venue in the SFJAZZ Center.

It’s the latest show in SFJAZZ’s decade-old Hotplate series, which presents the Bay Area’s top players, performing the music of legendary jazz artists. There have been dozens of Hotplate events through the years: bassist Marcus Shelby played Coltrane’s Giant Steps; saxophonist Howard Wiley reimagined Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come; and harpist Destiny Muhammad took a trip through Alice Coltrane’s Journey In Satchidananda. Upcoming Hotplate shows will include guitarist Mason Razavi performing Wes Montgomery’s Boss Guitar (Nov. 21); singer Lori Carsillo interpreting songs from the Nancy Wilson/Cannonball Adderley collaboration of 1962 (March 19, 2020); and drummers Jaz Sawyer and Jeff Marrs recreating the Rich Versus Roach LP, which captured a 1959 faceoff between Buddy Rich and Max Roach (April 16, 2020).

JuJu is a natural for Hotplate.

Wayne Shorter

Now 86, Wayne Shorter is the Yoda of jazz, a master of secret harmonic motion and a player whose soloing style has grown increasingly economical and cryptic. But JuJu is from an earlier time, when Shorter — under the spell of his friend Coltrane — was seeking a kind of raging beauty within the forms of his compositions. “Deluge.” “House of Jade.” “Mahjong.” “Yes or No.” “Twelve More Bars to Go.” The tunes are unforgettable, and Shorter’s quartet — it’s essentially Coltrane’s band, with Jones, pianist McCoy Tyner, and bassist Reggie Workman — feels oceanic, feeding raw energy to the saxophonist as his solos move up, up, up in a boiling spiritual ascent. It’s one of the best records of the 1960s — hell, of any era. It never gets old.

A JuJu fanatic going back to the early ‘90s, Hanrahan wonders if Coltrane was paying close attention to Shorter’s recording during the latter half of 1964: “You can hear things on JuJu that you then hear on A Love Supreme. The timbre is the same. The feel is the same,” Hanrahan says. “You’ve got the same rhythm section, minus Reggie.” (Jimmy Garrison is the bassist on A Love Supreme, though Workman also performed and recorded with Coltrane in the early ‘60s.) Listening to Jones’s solo on “Mahjong,” Hanrahan hears a precedent for the drummer’s famous solo on “Resolution,” the second movement of A Love Supreme: “Very similar solo,” he says. “Just the way he starts off with the cymbals, this light, touchy feel.”

Hanrahan’s comments sound like the beginnings of a PhD thesis, though, he concedes, similarities between JuJu and A Love Supreme may simply have arisen “through osmosis. Wayne and Coltrane, those two really just had a lot of crossover sounds and tones. I think they just played off each other and grew off each other. Because they were contemporaries, both exploring, and they both went into spiritual worlds as a way of accelerating their personal and professional growth.”

And for both, Elvin Jones was “the key element.”

Growing up in the Chicago suburbs, Hanrahan listened to the Beach Boys, the Beatles, Kiss. His oldest brother, Bill, gave up the drums and passed them along to John, who started playing with another brother, Mark, a guitarist, and Mark’s friends: “We did a lot of classic rock tunes: Black Sabbath, Robin Trower, Beatles.”

Early on, Hanrahan’s mother had taken him to a concert by singer Pearl Bailey and her husband Louie Bellson, the great jazz drummer who had worked with Duke Ellington’s band. “It was an eye opener,” says Hanrahan. By the end of high school, he and his brother were covering Grateful Dead tunes along with ones by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk. Also, Hanrahan was hanging out at the Jazz Showcase in Chicago, where he saw one drum master after the next: Max Roach, Art Blakey, Roy Haynes and Elvin Jones.

Hanrahan had rarely taken a jazz lesson, however; he counted himself as a rock drummer. That started to change in 1987, when he was 20 and took some lessons with drummer Paul Wertico, who lived in Skokie, outside Chicago, and soon would join Pat Metheny’s trio. At the first lesson, Hanrahan told his teacher that John Bonham (of Led Zeppelin), Keith Moon (of The Who) and Mitch Mitchell (of the Jimi Hendrix Experience) were his main influences. He recalls telling Wertico that certain sounds seemed intrinsic to those drummers: Bonham’s virtuoso use of triplets and quads; Moon’s rolling rhythms; Mitchell’s singular paradiddles. Wertico then asked him a question: “`Do you know where all of this comes from? The guy who started this is Elvin Jones.’ And he told me how Elvin’s approach to playing drums is like no other drummer. It’s all about the subdivisions. The study of Elvin Jones is the study of the triplet, the placement of the triplet.”

Jones was renowned for dividing quarter notes — which carry the basic pulse of a tune — into triplets, that is, three beats per pulse. He then orchestrated the different triplet notes, assigning them to different sounds in his drum kit — the snare drum, bass drum or hi-hat — all while maintaining a steady pattern on his ride cymbal. It was a remarkable new example of what jazz drummers call “independence.” Jones was engaged in a kind of perpetual motion: “His main achievement,” jazz historian Leonard Feather once wrote, “was the creation of what might be called a circle of sound, a continuum.”

Elvin Jones performs with the John Coltrane Quartet

Hanrahan was intrigued by Jones: “God, what a genius,” he says, recalling how he began to explore the drummer’s oeuvre — including JuJu which he discovered in 1992 or ’93, playing it over and over on a cassette in his car.

In 1999, Hanrahan moved to Santa Cruz where he later hosted a weekly show on a public radio station, KUSP-FM. When Jones brought his Jazz Machine to the Kuumbwa Jazz Center — the club in Santa Cruz — in April 2003, Hanrahan asked the drummer if they could tape an interview for the show. Sure, Jones replied, inviting Hanrahan to sit down with him at Yoshi’s jazz club in Oakland, where he was about to play for the next few nights. Hanrahan attended every show, and then followed Jones to Los Angeles, where the drummer played at the Jazz Bakery and finally sat down to talk. Hanrahan was struggling with a drinking problem at the time, and Jones, who had faced similar issues, began talking about Coltrane’s addictions — how the saxophonist had overcome them in 1957, and how this “awakening” eventually led to the making of A Love Supreme. Jones said to Hanrahan, “'Let me tell you about it,’ and he explained, 'John wrote this as his way of thanking God for his life, for his health and his sobriety.’”

Hanrahan felt the hand of serendipity. Earlier in the month, walking past City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, he had noticed a volume in the window: A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album, by Ashley Kahn. Hanrahan went inside, flipped through the book, and noticed the album’s recording date: Dec. 9, 1964. He was born exactly two years later, on Dec. 9, 1966: “Unbelievable. It just rang in my head so much,” he says, “the whole idea of playing music for a purpose. Why am I here? I needed something to get me through this addiction. And in the spring of 2003, I was just in a very manic state going through sobriety, and all I did was listen to A Love Supreme.”

John Hanrahan

Flash forward to 2014 when Hanrahan and his quartet performed the suite — recorded 50 years earlier — at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center and the Monterey Jazz Festival. In the years since, Coltrane has continued to inspire Hanrahan, who has been fully sober for a decade — and has a tattoo that says “A Love Supreme” on his left arm, a reminder to stay away from alcohol. Earlier this year, he recorded an electric version of A Love Supreme (along with Coltrane’s Meditations) with a band including guitarist Henry Kaiser and saxophonist Vinny Golia. Pondering future projects, Hanrahan identifies several other albums he might explore, including Olé Coltrane and McCoy Tyner’s The Real McCoy.

Both those albums share a key element: Elvin Jones.

But next up is JuJu, which continues to blow him away. He describes Jones’s performance on the second track, “Deluge”: “That’s probably my favorite song on the album, the ballad itself, which Wayne composed, and the tension Elvin is creating; it’s so subtle, the accents he’s doing on that, his triplet feel. Oh, my God. Elvin is literally just surrounding Wayne; it’s like he’s parachuting around Wayne, covering him, from all different angles — surrounding him! What a masterpiece.”

Hanrahan expects his band to “crush it” at SFJAZZ on Sept. 19, but he confesses to feeling “a little overwhelmed. Because honestly, I’ve always been a rock drummer, playing jazz. I do not feel worthy, playing this music. But it’s getting better, and lately I’m starting to think to myself, `You know, John, you’re a jazz drummer.’ I tell you, it’s a process, playing this music. I’m very humbled by it, to say the least. I don’t take this shit lightly — keeping the spirit alive.”

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.