A LOOK BACK AT

ART BLAKEY & THE JAZZ MESSENGERS MOANIN’

November 14, 2016 | by Rusty Aceves

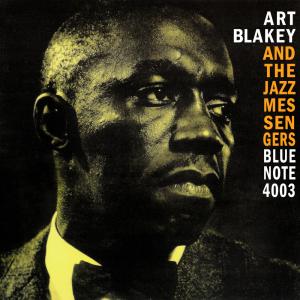

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Photo by Ben van Meerendonk)

We take a look back at the Blue Note classic, Moanin’, by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’.

In the history of jazz, few bands were as long-lived or highly regarded as Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, and none have rivaled the now-legendary ensemble as an incubator of young talent destined for stardom. Though originally founded in 1954 as a collaborative effort by both drummer Art Blakey and pianist Horace Silver, the Jazz Messengers became a sole proprietorship under Blakey following Silver’s departure in 1956, and recorded a string of albums for various labels with a lineup dubbed the “Second Messengers” featuring trumpeter Bill Hardiman, pianist Sam Dockery, bassist Jimmy “Spanky” DeBrest, and either Jackie McLean or Johnny Griffin on saxophone. After a break of over a year, Blakey wanted to explore with a new crop of musicians, and started fresh with a quintet made up of Philadelphia natives: trumpeter Lee Morgan, tenor saxophonist Benny Golson, pianist Bobby Timmons, and bassist Jymie Merritt. Their first album together marked Blakey’s return to Blue Note, and stands as a highlight of not only the drummer’s oeuvre, but of small group jazz in general. Recorded in a single session at engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack, New Jersey studio on October 30, 1958, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers (more commonly called Moanin’) is one of those rare confluences of musicians and material that yields a result greater than the sum of its parts. Beyond the blues stomp of Bobby Timmons’ title tune, Moanin’ boasts the first appearance of tunes composed by Golson that remain staples today including “Are You Real,” “Along Came Betty,” and “Blues March.” A drum-centric Blakey piece, “The Drum Thunder Suite,” and a take on Arlen and Mercer’s “Come Rain or Come Shine” completes the set.

In the history of jazz, few bands were as long-lived or highly regarded as Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, and none have rivaled the now-legendary ensemble as an incubator of young talent destined for stardom. Though originally founded in 1954 as a collaborative effort by both drummer Art Blakey and pianist Horace Silver, the Jazz Messengers became a sole proprietorship under Blakey following Silver’s departure in 1956, and recorded a string of albums for various labels with a lineup dubbed the “Second Messengers” featuring trumpeter Bill Hardiman, pianist Sam Dockery, bassist Jimmy “Spanky” DeBrest, and either Jackie McLean or Johnny Griffin on saxophone. After a break of over a year, Blakey wanted to explore with a new crop of musicians, and started fresh with a quintet made up of Philadelphia natives: trumpeter Lee Morgan, tenor saxophonist Benny Golson, pianist Bobby Timmons, and bassist Jymie Merritt. Their first album together marked Blakey’s return to Blue Note, and stands as a highlight of not only the drummer’s oeuvre, but of small group jazz in general. Recorded in a single session at engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack, New Jersey studio on October 30, 1958, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers (more commonly called Moanin’) is one of those rare confluences of musicians and material that yields a result greater than the sum of its parts. Beyond the blues stomp of Bobby Timmons’ title tune, Moanin’ boasts the first appearance of tunes composed by Golson that remain staples today including “Are You Real,” “Along Came Betty,” and “Blues March.” A drum-centric Blakey piece, “The Drum Thunder Suite,” and a take on Arlen and Mercer’s “Come Rain or Come Shine” completes the set.

In his liner notes for the album, Leonard Feather wrote:

Not for nothing did Art Blakey select the term Messengers to denote his musical and personal purpose at the onset of his bandleading career. Manifestly all meaningful music carries its own built-in message, and to this extent the term could reasonably be applied to any combination of performers. What is more important in Blakey's case is that his message is transmitted not merely in his music but in his words and speeches, his actions and personality.

This characteristic of Blakey has been increasingly evident during the eventful years since he gave up his job as a sideman. He has made it clear that he will never be content merely with the knowledge that his musical message is correctly construed, its rhythmic syntax and melodic grammar unimpeachable. This is merely the starting point for Blakey, once equipped to deliver his message he is determined to find an audience for it, and for all of jazz. He is not merely a spokesman for Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, but a pleader for the whole cause of modern music.