2020 NEA JAZZ MASTERS:

A Q&A with Dorthaan Kirk

August 10, 2020 | by Richard Scheinin

Dorthaan Kirk (photo by David Tallacksen)

For the second installment of this exclusive series of Q&As with the 2020 NEA Jazz Masters, SFJAZZ Staff Writer Richard Scheinin spoke to tireless jazz advocate, jazz radio pioneer and 2020 NEA Jazz Master Dorthaan Kirk. Scheinin will be posting conversations with new Jazz Master Roscoe Mitchell and with drummer Terri Lyne Carrington, Music Director of the NEA Jazz Masters Online Tribute Concert, in advance of the live stream on August 20 at sfjazz.org and arts.gov.

Dorthaan Kirk is a keeper of the jazz flame. She is an energizer, a crusader for the music, mentoring and motivating musicians far and wide over the past 40-plus years. They call her “mom.”

She is a talker, warm and without airs. During a phone call from her home in East Orange, New Jersey, she laid out her story: Raised in Texas—in Houston’s Third Ward—she listened to the blues; guitarist Albert Collins was her cousin and playmate. She heard Duke Ellington on the radio, began hanging out in neighborhood jazz clubs, and moved to Los Angeles. There she became part of the informal network of families who opened their doors to traveling musicians, offering home-cooked meals. That’s how she met her future husband, the legendary multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk. He later recorded a tune for her, “Dorthaan’s Walk,” which captures her swinging gait and soulful energy. And it was through Rahsaan that she was introduced to so many musicians, visual artists, actors and poets—the Eulipians, as he called them.

After her husband’s untimely death in 1977 at age 41, she took up his mantle. In 1979, she went to work for WBGO, the brand-new jazz radio station in Newark, New Jersey. She became its heart—“Newark’s First Lady of Jazz,” extending the station’s mission, establishing a series of children’s concerts and community-based arts initiatives. At her Newark church, she co-founded a free Jazz Vespers concert series, presenting A-list talents including Jon Faddis, Gregory Porter and the late Jimmy Heath—her friends, happy to perform when invited by Dorthaan Kirk. Bassist Christian McBride has described her as “the most unanimously loved person in the jazz world.”

During our conversation, Dorthaan—who joins Reggie Workman, Roscoe Mitchell, and Bobby McFerrin in the 2020 class of NEA Jazz Masters—talked about “bright moments,” one of her late husband’s favorite phrases. He used it to describe the spiritual uplift that music can bring, but also the small things that make life a joy: a great meal, a good joke, a warm conversation. Dorthaan Kirk, 82, is all about bright moments. When we spoke, she had just been going through old photos. A friend in publishing has urged her “to put together a book, nothing fancy, a photo book with captions, some kind of history of my life—and I’ve lived a long time! I’ve got thousands of photos. So I have a plan to invite my friends over one by one, and we’re going to sit on the deck—safely distanced—and talk and cook and hopefully get down to work on this new project.”

Q: How did it feel to learn you’d been named a “Jazz Master”?

A: I was pretty much speechless and stunned. I can’t think of any other words. It was unbelievable, out of the blue. I never thought in a million years—never, you know? I had pretty much kept track of who had won the award before this, and of course they all deserved it a million times over. So I was just speechless—and I’m never speechless. I am a huge talker!

I’ll put it this way: I don’t think I could function well the next couple of days because it was just too good to be true. But finally, it was like, “Darn, it is true!”

Q: Has it made you reflect on all your experiences, and why the National Endowment for the Arts has honored you like this?

A: I’m just guessing how it happened. But firstly, I think it’s because of my time traveling on the road with Rahsaan, and, secondly, it’s probably due to my being a founder at WBGO. We did all kinds of things at WBGO. We even did art gallery shows, and I was in charge of those. So not only was I able to give a lot of exposure to musicians and performing artists, I was also able to give it to visual artists. Then 20 years ago, I began presenting jazz at my church in Newark. And I also have presented jazz at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. In fact, I would love to know how many people I have reached over the years, especially young people, because I produced a WBGO Kids Jazz Concert Series for 25 years—which seems impossible! We would do 10 of those shows each year… I’ve had (trombonist) Steve Turre. I’ve had (singer) Vanessa Rubin. I’ve had (drummer) Jerome Jennings. I’ve had (pianist) Henry Butler before he died. And we presented them in different venues in New Jersey and one time in New York. It makes me tired just thinking about it!

So I guess all of that adds up to something.

Q: And you didn’t solicit any of this work? People just asked you to do it, and it kind of kept growing through the years?

A: Right. I didn’t conjure any of it up; it all just came to me. And I have to say I was an associate producer for Jazz at Lincoln Center back in the early days. And the person who was the producer, to be honest, she didn’t know Betty Carter from Carmen McRae or anything else. But she knew jazz was valid… And she found me at WBGO and together we came up with these different concepts, and I was the one who knew the musicians and knew how to contact them. A couple of years ago, Wynton (Marsalis) and I reminisced on this. He said to me, “I was young back then. And thank you for all you did for the musicians.” And I said, “Well, Wynton, it just came my way. I just did the best I could and embraced it.” And Wynton said, “Well, you know, not everybody embraces what comes their way,” and that kind of stayed with me, his saying that.

WBGO pays tribute to Dorthaan Kirk

Q: In a nutshell, what’s your legacy?

A: If I decide not to get cremated, my tombstone might say something like: “She tried to make a difference to as many people as she could.” That about sums it up.

Q: What’s the hardest part of what you’ve done?

A: One of the worst things about putting on an event is worrying: “Are people going to come and are they going to enjoy it?” You can have nightmares over that. The worry is the thing. It could give you an ulcer.

Q: Was Rahsaan a worrier, too? I have a feeling he wasn’t.

A: He always looked forward to performing at certain places—like the Vanguard. He loved the Vanguard and Max (Gordon, owner of New York’s Village Vanguard). It was standard that he performed at the Vanguard four times a year, because Max loved him. And when Rahsaan performed at Keystone Korner in San Francisco—he always looked forward to going out there and that was a favorite. I know Joe Segal’s place in Chicago (the Jazz Showcase), that was a favorite, too.

Q: Tell me about the neighborhood where you grew up in Houston.

A: That’s the Third Ward, the part of town that George Floyd lived in. In fact, the school that George graduated from was my alma mater: Jack Yates High. I just made a donation. And as it turns out, my sister’s son, my nephew, played football with George in high school. And where he’s buried is about five miles from where my niece lives. My sister went to see the (funeral) procession—and don’t you know the procession went right down her street and she took pictures and she sent them to me and I posted those on Facebook. So it felt pretty close to me, even though I’m 1700 miles away. My sister ended up getting interviewed by local media in Houston. And by the way, my niece belongs to the church where the funeral was.

Q: You still feel a connection to Houston?

A: Sure. I left Houston in 1955 to go to college in Los Angeles, but I never stopped going home to visit. I’m the mysterious auntie that pops up from time to time.

Q: Was music important to you as a girl?

A: Yes. It was fun and social and you probably already know that jazz was in the streets. And Houston was a blues town; Albert Collins is one of my cousins. And I have to tell you, my parents didn’t even have a TV. So radio was very large. I listened to the radio a lot, especially when I was doing my homework. And I used to tune in this station that came out of Del Rio, Texas, and I listened to country music. In fact, years later when I went to WBGO and told people I was a big Dolly Parton fan, they said, “What?” Well, I grew up in Texas, listening to the radio! And sometimes my friends would fix me up and smuggle me into clubs, or take me to places like the Auditorium in downtown Houston, which was like our Apollo, our Carnegie Hall.

Q: Who’d you see there?

A: I can’t remember. That was over 65 years ago!

I was just blown out of the water. I was mesmerized. All I can tell you is, I just hadn’t heard and obviously had not ever seen a musician playing three horns at one time—and sounding good!

Dorthaan Kirk, on the first time she saw Rahsaan Roland Kirk perform

Q: OK, who did you hear on the radio?

A: Everybody: Ruth Brown, Little Willie John, Duke Ellington. When I grew up, nobody told me what was “America’s art form” or whatever. I just listened to the radio. And like I said, Houston was a blues town, and Albert (Collins) must’ve been about six years older than me. When he was real young, he would get a broomstick and pretend he was playing a guitar. Little did I know he would grow up and be famous in the blues world.

Q: He lived in the Third Ward, too?

A: He did. And when I was growing up, if somebody was five or eight years older than you, you had to listen to them as if they were your parents—because they were older. And that’s how I grew up with Albert, and until the day he died, he called me “baby.”

Q: Paint me a picture of life in the Third Ward when you were growing up in the 1940s and early ‘50s.

A: We’d play hopscotch. We played jacks—games these kids today have no idea about. And then in the neighborhood on different corners they would have what you call a juke joint, and then even though you couldn’t go in, because they served liquor, you could stand outside and listen to the music coming from the jukebox. So it was our fun. My mother didn’t say, “Listen to this, because it’s America’s art form.” I didn’t know that until many years later. Many.

And of course, when I grew up, Houston was segregated. When I left Houston, they hadn’t even passed the desegregation law.

Q: You moved to Los Angeles—what was the music scene like when you arrived there?

A: The scene was bursting all over. I had just turned 17 in July 1955, when I got there. My great aunt had left Texas many, many years ago and established herself in LA. And somehow she told my mother to send me out and go to school, because it’s much cheaper there and she also felt it would be good for me to experience getting away from the environment in Texas. Aunt Jessie, we called her.

Q: Was she into music?

A: Oh no, she was a good old Methodist. But she didn’t object to music. And don’t you know, I went to Los Angeles City College and I remember seeing Elvis Presley there; nobody had a clue about him at the time. And do you remember H.B. Barnum, who ended up to be Lou Rawls’s music director? I remember him doing a show. And they had clubs all over the place, and they had the Sunday morning jam sessions. And I remember the first time I ever saw Miles Davis was at the Adams West Theatre; you can probably google it. It was on Adams and Crenshaw Boulevard, and they would have big names performing there after they got out of the clubs. I saw a bunch of them.

Q: Miles made an impression on you?

A: I don’t know. It was the thing to do. Everything was good, okay? We didn’t dissect the music. We were just having a good time, slurping Coca-Colas with a lot of ice in it. But I guess so! I remember seeing him and, again, others, too. But I guess Miles Davis stood out many years after, because I got to meet him and talk to him, and he and Rahsaan were on the same concert many years later at Howard University. Many of those people I ended up meeting and knowing—it was amazing.

Q: When did you first see Rahsaan perform?

A: I first saw Rahsaan—I want to say, must’ve been ’62 or ’63 at the It Club on Washington Boulevard in Los Angeles. And the reason I got to see him—my first husband was originally from Baltimore, and he and a bunch of friends used to get together on Saturdays and play jazz records from time to time. And this one time, this guy named Curtis brought this LP and it was by guess who? Roland Kirk. And he went on to tell how he knew Roland Kirk and so on and so forth. He had met him in some town—Odessa, Texas, or somewhere—and this friend was a local drummer; his name was Curtis Brown. I challenged him: “You don’t know nobody who makes records. You’re just a local cat!” He said, “OK, next time he comes to town, we’re going to see him and you’ll find out.” And that was the It Club. (Bassist) Vernon Martin was in the group, and I think (pianist) Rahn Burton. I forget who was the drummer—and I remember they all wore suits!

Q: And did Curtis Brown make a point of greeting Rahsaan when you got to the club? Was it like, “So do you believe me now, Dorthaan?”

A: He didn’t rub it in or anything like that. It was just obvious that he knew Rahsaan.

Q: And what did you think of the music?

A: I was just blown out of the water. I was mesmerized. All I can tell you is, I just hadn’t heard and obviously had not ever seen a musician playing three horns at one time—and sounding good! I’m not a musician. I’m a lay person. And after that, when he came back to town, he became friends with my family. I have always been able to cook, I guess because I was the oldest of five children. And musicians are always looking for a good home-cooked meal when they’re on the road, and my house became the place for Rahsaan to get a good home-cooked meal.

Q: I’ve lost track of the chronology. Were you still living with Aunt Jessie?

A: No! This was after I messed up in school, got married and had kids! This was when I was married to my first husband. So my children grew up knowing Rahsaan from that point on. Interestingly enough, my youngest daughter was terrified by Rahsaan, because I guess you could say he was different. They had never encountered someone with a physical—I’m trying to find the right word, because Rahsaan hated “blind” and “disabled” and words like that. If you ever saw him perform, you know he did most of his politicizing on the bandstand. He’d say, “I’m not blind, I just don’t see like the rest of you see.”

Q: What did you cook for him in those early days, after you first met?

A: Anything that was soulful, because to this day, I’ve never been into fancy food. So it was the usual: chicken, roast, pork chops, greens, candied yams. Many years later, food was what he loved most next to music, and it became his enemy because of his health issues before he died. Certain things he wasn’t supposed to eat. And he always had his own ways of dealing with that. And he would tell his doctors, “If I can’t have what I want to eat, I don’t even want to be here.” He didn’t live in the world we live in. Food was important; it gave him a certain kind of pleasure, of joy. He lived in a world of sound and taste and feel. We live in a world of seeing everything, bad and good and indifferent, and everything in between.

Q: What year were you and Rahsaan married?

A: 1971

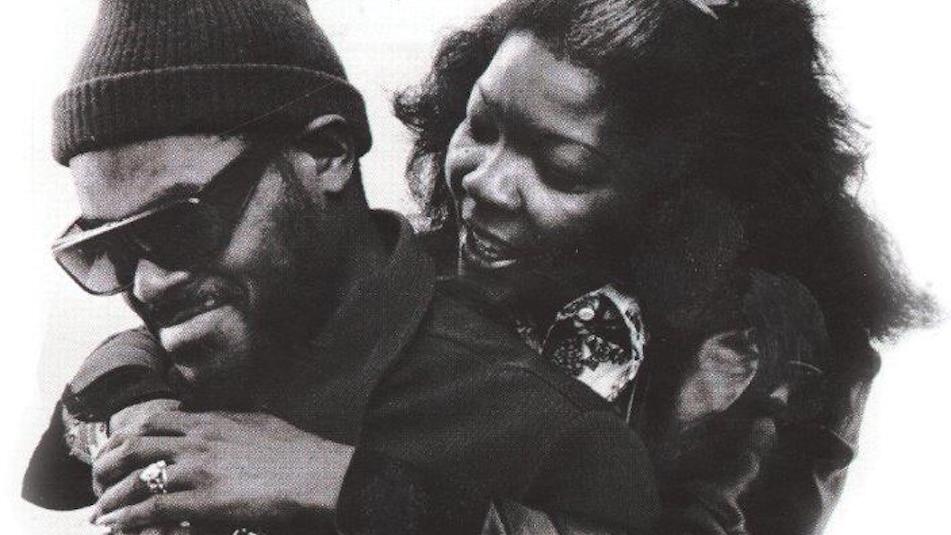

Rahsaan and Dorthaan Kirk

Q: I want to ask you about his tune “Theme for the Eulipians”—the one where he talks about the world of spirit and the arts and the people who live in that world. (The song is on Kirk’s album The Return of the 5000 Lb. Man, from 1976.)

A: The lyrics are by Betty Neals, the poet. She was my youngest daughter’s teacher at school in East Orange, New Jersey. And my daughter knew that she was different than her other teachers, because she played jazz records in the classroom, including by Rahsaan. And that’s when my daughter went up to her and said, “Miss Neals, that’s my stepfather.” And that’s how Rahsaan heard about her, and she came to the house. She came up here and she would sit in that music room with Rahsaan, and he told her how he thought of these Eulipians, and she would write the words.

Q: Who exactly are the Eulipians?

A: It’s any artist, be they poets or visual artists or performers. And all of the people that support the great music—they’re Eulipians, too. It’s not mysterious, but it’s all of those people. If you don’t yet fall into one of those categories, you’re not a Eulipian.

Q: I guess you’re a hardcore Eulipian.

A: Sure, because I’ve always been a part of it. See, by the time I met Rahsaan, I had already been listening to the music since I was very young. Being with him just made me more aware of it as an art form. I started to know who the musicians were. I started to know all the songs on an album, from reading the covers to Rahsaan when we would go to the record store. So I became more knowledgeable about it, as opposed to it being just a form of entertainment. After he died, there was a lot of stuff I didn’t really even know I knew until a situation would come up. I think they call that “subliminal.”

Q: What kind of information did you have tucked away in your head?

A: Who’s on this record. What instruments do they play. Before him, I didn’t try to remember who the side people were. I didn’t care. The leader was whoever it was and the music was good. But then with Rahsaan, I started to learn why this one is important and what goes into making a song.

Q: On the recording, Rahsaan describes Eulipeans as “journey agents.” Have you been on a journey all these years?

A: I guess the journey is all of the things that I told you that I have done and continue to do in jazz. Yeah, I guess I’m on a journey. And much like George Floyd—and I don’t want to get heavy. But if you really look at George and know where he lived in low-income housing and how he tried to get the kids to do better—he was trying to accomplish what he was put on Earth to do. But the way George died, you just have to say that was his assignment on Earth, okay? And I said that because I want to say this: None of these things that I have done at the church, at WBGO, at NJPAC (New Jersey Performing Arts Center)—all those people came to me and said, “We need you to do this.” It was just that being a journey agent was my assignment on this earth. Stuff keeps coming to me. You know how a lot of people, they go to school and they become a doctor or a lawyer or whatever? Well, I didn’t set out to do any of the things I have done. That’s why I know this is what I was supposed to do on Earth.

Q: A lot of musicians call you “mom.” What kind of guidance have you given them over the years?

A: I’m not stupid enough to tell them what to do! But when WBGO started I was like 40 already—that was old, compared to everybody else. So I was the elder. And based on all the experiences I had from traveling with Rahsaan, I would share, you know? I had learned simple things, and I shared them with producers and promoters, the people who booked the musicians. I had learned that musicians should always have some kind of refreshment. Don’t just bring them somewhere and make them play and don’t give them waters, sodas, whatever. I really, really learned the worst thing you could do was give a musician a bad piano, a bad sound system—and so I passed that on. Again, it was stuff that was in the back of my mind, that I didn’t know was there: “For God sakes, do your very best to promote these musicians in every way you can.” Simple stuff like that; you’d be surprised by some of the things the musicians went through. “And for God’s sake, please pay them as much as you possibly can, because it’s their livelihood.”

Q: You were taking care of the musicians by impressing those things on the promoters.

A: Right. I always made sure to the best of my abilities that those things were taken care of for the musicians, especially since my whole career has been non-profit, you know? I never had the big buck, though I’ve paid musicians some fairly decent money. I tried to make them feel good about the things that I had asked them to do. So I guess that’s how slowly I became the “mother.”

Q: You know the jazz community as well as anyone. Are there any musicians out there who you think should become NEA Jazz Masters in the years ahead?

A: I have to really think about that, because my generation—my generation is dead. And things have changed.

Well, did Kurt Elling get it yet? I would say Kurt Elling. Kurt is one of the most unique singers that I have heard. I just love him to death.

And I would say Gregory Porter, because he paid a lot of dues to get to where he is. I had Gregory Porter twice at my church, and I told people, “He deserves to be large.” Well, Gregory stood up there and he sang “Amazing Grace”—and he turned my church out. They died and went to heaven. One of my deacons went home and played his CD all afternoon.

Gregory has something that I don’t hear in singers anymore. He can just stand up there and just sing, and you feel it. God bless him.

Those were some bright moments.

The 2020 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert will take place on Thursday, August 20th from 5-6PM PT. It can be streamed without charge at SFJAZZ.org and arts.gov.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.