2020 NEA JAZZ MASTERS:

A Q&A with Reggie Workman

August 3, 2020 | by Richard Scheinin

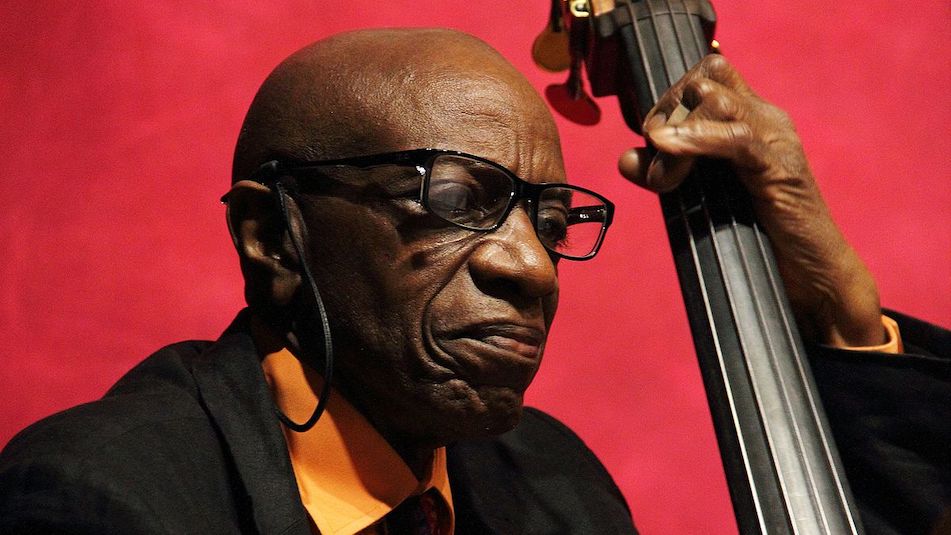

Reggie Workman

In the first of four Q&A posts, SFJAZZ Staff Writer Richard Scheinin speaks to Reggie Workman, legendary bassist and 2020 NEA Jazz Master. Over the next two weeks, Scheinin will post conversations with two other new Jazz Masters—Roscoe Mitchell and Dorthaan Kirk —and with drummer Terri Lyne Carrington, Music Director of the NEA Jazz Masters Online Tribute Concert on August 20.

Reggie Workman is one of the greatest bassists in jazz. He is the glue on one classic album after the next: Art Blakey’s Ugetsu, John Coltrane’s Impressions, Freddie Hubbard’s Hub-Tones, Wayne Shorter’s JuJu.

It all began in Philadelphia, where Workman was part of a singular explosion of jazz talent across the city’s Black neighborhoods during the 1950s. One of these days, someone will make a movie about that time and place. It’s as if Workman and his friends — Lee Morgan, McCoy Tyner and Archie Shepp, to name three of many — were a secret society of musical Kung Fu masters, destined to leave their mark. By the time he moved to New York, Workman was ready to play with Coltrane — also from Philadelphia — as well as with Blakey, Max Roach, Cecil Taylor and scores of others. A musician without boundaries, Workman can swing a band to death — or “take it out to some other galaxy,” as he says. Whatever the musical situation, he elevates it.

A member of the 2020 class of NEA Jazz Masters — along with Roscoe Mitchell, Dorthaan Kirk, and Bobby McFerrin — Workman, 83, recently picked up the phone in his Harlem apartment and discussed all of this. Without a whiff of ego, he answered questions about his more than 60-year career, his musical approach, his “calling” to be a teacher, and his ongoing search for a personal sound. As a musician, he said, one has a responsibility to “charge your sound with a particular prana, a particular energy that is unique only to yourself. And nobody can sound like that but you, because that is your fiber and your transmission.”

Trio 3 at the Village Vanguard (L-R: Oliver Lake, Andrew Cyrille, Reggie Workman. photo: Tina Fineberg)

Q: You’ve played with Herbie Mann and with Cecil Taylor. Not everyone can pull that off. How do you adapt to so many different musical situations? Have you always had a broad conception?

A: I think so. With each situation in life that you come across, if you are sincere about being a musician, you want to do the best you can. Different strokes for different folks.

Cecil is one thing. We go back way before I was with Herbie Mann. Because Cecil’s been there since I was first in New York in 1958 or ’59: Cecil, Roswell Rudd, Bill Barron, Don Moore, Tootie Heath, Lee Morgan, Spanky DeBrest — they all lived on East Sixth Street, which is now Indian Restaurant Row.

So you have all kinds of people that you come in contact with: Gigi Gryce, Jackie McLean. My philosophy became that you do the best in every occasion, and it’s all about creating a musical dialogue. I want to have the best dialogue I can, just like in spoken conversation.

You walk into a room, you don’t know who you’re going to encounter — it could be anybody. And you’re not going to stop talking to someone because they’re from a different place than you. You try to find a common thread, because every area that you want to do deal with, you should be able to do your best. I want to be the best I can be at that moment. And maybe there’s someone else who just wants to play Broadway shows, and they work just on that area. And doing just that is still a helluva feat. But you notice that many of the musicians who came along with me, they had to do everything — played Broadway shows, played the clubs, played the lofts, and went on the road. They had to be ready. If Miles Davis called me to go on the road, I had to be ready.

Q: I spoke to Roscoe Mitchell who said his musical personality comes from growing up in Chicago — that’s where he got his do-it-yourself attitude. When it snowed, people in his neighborhood would put buckets out to catch the snow and make ice cream.

A: We did that in Philadelphia, too!

Q: Did Philadelphia contribute to your broad musical thinking, your adaptability?

A: For sure. Philadelphia had a bunch of great musicians, some still living today — though many of my companions have jumped off the planet. And all the seeds that we planted while we were there are still blooming around the world. Philadelphia is close to New York, and people come to live there, because it’s right down the street from New York City. They say, “I’ll stop in Philadelphia, there’s a lot of great musicians there.” There were a lot of clubs and places to play, and therefore you can jump in the car and go up to New York and listen to what’s happening and then go back to work on your own thing.

Q: You’re from the Germantown neighborhood, right? Archie Shepp was there when you were kids?

A: Yes, Archie and I kind of grew up in the same neighborhood, and Lee Morgan was nearby. There were so many musicians all over Philadelphia: Donald and Stanley Wilson, Rashied Ali, Owen Marshall, Tommy Monroe, Johnny Splawn, Odean Pope, Sonny Fortune, Tootie Heath, Kenny Rodgers. I mean, I could go on and on: Eddie Campbell, Clarence Sharpe, so many names. Eddie Mathias was one of my mentors; he’s still around, but not doing so well these days. There was another bass player — Nelson Boyd was just across the bridge in Camden where Buster Williams is from. Groove Holmes. Jimmy Smith. McCoy Tyner was from Philadelphia. The longer I talk, the more names I will come up… like Henry Grimes and his brother Lee. So Philadelphia was a place you could get around with the trolley or the subway and you just go to where the music is.

Q: You played piano as a kid, but gave it up when you were around 12?

A: (Workman pauses before answering.) I’m so sorry I let that go. The streets called me — sports — and I’m still paying for giving that up. Now the bass started in eighth or ninth grade; that’s when I actually began playing. But the interest started earlier, because my cousin Charlie Biddle, he’d hold me and the bass — he’d have me standing on the chair, holding the bow, and he’d make the sound. He’d say, “This is the way it feels and this is the way it sounds and this is how you feel the vibrations.” And I said, “I want that to be my vocal chords, my voice; I want that to be my sound.”

And then in eighth grade, at first they gave me a tuba, because that’s what was available. And finally they gave me the bass, my first bass. And Philly Joe Jones — there’s another name — he was one of the guys who had some fun with me, because I had to carry the bass to school. You know, Philly Joe was a trolley car driver, and I ran into him a couple of times on my way to school, and he would laugh at me, carrying my bass.

Q: Can you remember your first professional gigs?

A: At the YMCA for dances, and at the town hall and different cabarets where people used to have their birthday parties and different celebrations. And there were the Holmes brothers — one was a drummer and one was a guitar player — who used to hire us. And we used to go out to Willow Grove, which is where Bud and Richie Powell lived, and we would play gigs with the Holmes brothers, which was R&B. So we had all kinds of situations, musical situations.

Q: You also had a trio with McCoy Tyner?

A: Yes, McCoy and I had a trio with Eddie Campbell, who was a drummer; he died young. And we worked at the House of Jazz in Philadelphia and we were the house trio and the club would bring in names. (Workman’s recollection is that the club was on or near N. 27th Street in North Philadelphia.) And one of the names they brought in was Coltrane, because McCoy was there and McCoy and John Coltrane were good friends. So the club owner told him, “Call John.” And that’s where I got to hear — and not just hear, but experience — how great he was.

That was back, I guess, in the ‘50s, the late ‘50s.

Q: You were a teenager, or just out of your teens.

A: Yes. Oh, I just remembered more names from Philadelphia: Cal Massey and his family, and Steve Davis and his family. That’s another community, where you had McCoy and Trane and Steve Davis and Cal Massey and their families — the Muslim community.

John Coltrane Quartet on German TV, 1961 (L-R Elvin Jones, John Coltrane, Reggie Workman, McCoy Tyner)

Q: Did your relationship with Coltrane continue after you left his group?

A: Jimmy Garrison had taken my place. I was with John Coltrane up to about 1961. We did a lot of work together off and on in New York. We traveled together, we did tours together, we were friends. And I was delighted and honored to be in the band. It taught me a lot about what can happen with the music. Because I had been working more with people like James Moody, Yusef Lateef, Gigi Gryce and Freddie Cole, people who like their music done the way they do it.

And then when John Coltrane came along, he explained to me that I was to be myself. And that was a revelation to me, because here was a big name, a big person in my mind — and in the world’s mind — who said, “I hired you because of who you are and what you do, so do it. I’m having a hard enough time playing my instrument, so you figure out how to play your own.”

And that was a revelation to me. And what I came to realize was you can practice all kinds of technical things. But what you better practice is to be spontaneous and satisfy the needs of that very moment, the needs of the leader of the project, and your own expectations of yourself, because you are your own harshest critic.

Q: Art Blakey’s demands as a leader were more specific than Coltrane’s, is that true?

A: That was very different. Because Art had certain needs and certain desires as to the way he wanted the band to be, to look, to dress, to perform, to bow. And all of it had to be about the highest possible level of music he could possibly muster.

Q: In terms of leadership style, are you more like Coltrane or more like Blakey?

A: I’m more like Reggie Workman. I try not to be like either one of them, because they each had their own character and I could never fill their big shoes. But they have nurtured me to be what I am. And I feel I have one foot on each side. I don’t want to do only the music that Roscoe (Mitchell) is into or what Cecil (Taylor) was into, and I don’t want to do only what Gigi Gryce or James Moody were into. I want to figure out how my band can communicate musically in a situation — what are the needs of the situation? — and to have that kind of artillery to make it happen.

We have musical charts, of course. Certain tunes should be played close to the way it’s written, but certain tunes always have room for the improviser. I don’t think it’s sensible to hire a great improviser, who is an astute musician and an individual, and then expect them to become a secretary who takes dictation. So my band has always been such that, yes, you’ve got to learn the music, but once you learn the music, let’s take it out to some other galaxy.

Q: Roscoe Mitchell described improvisation and composition as parallel processes. He said they’re closely intertwined, in that one generates the other. Does that make sense to you?

A: That makes perfect sense.

Q: What are some words that describe your musical approach?

A: (Workman pauses.)

Q: I could throw out a few possibilities: “disciplined,” “spiritual,” “futuristic,” “traditional.”

A: It’s all of the above. And put that all under the umbrella of “universal,” because that covers all of us, no matter what language we speak. I wrote something once — it’s kind of a mantra for me, and I’d like to read it to you. But I’ll have to go find it, so why don’t you ask another question while I’m looking?

Q: Okay. When you think about your life and all the experiences you’ve had, does it strike you as normal — just the course of events that happened to you? Or do you think, “Wow! I did all that? How can that be?” And do you ever get nostalgic about the past?

A: I don’t look at it like, “Wow I did all that.” I look at it like, “Thanks to the Creator for allowing me to be on the scene to do all that, to do all I’ve done. And my job is not finished, because he hasn’t called me back yet, and I’m not done.” And I think all musicians are the same no matter where they are. There is something very important about music in that we are translators of the universal message that comes from on high. I don’t know if you’ve studied the Indian masters, but all the people are dealing with the same thing — the science of sound.

Okay, I found what I’m looking for. I’ll just read this for you in closing:

Among the widely varied arts disciplines there is a common quality of creativity.

A fundamental drive for communication exists among people of all nations whose languages vary widely, but is made common through music. Through music (the organization of sound) one is capable of reaching and communicating with all nations regardless of their emotional or intellectual experience.

I consider music, music education, composition, performance, the major catalyst for our world’s harmonious existence and my own vehicle for accomplishing the above.

I wrote that a long time ago. That’s what I believe. I want to make that my signature.

Q: I imagine you impress those beliefs on your students. Why has teaching been such a calling for you? You’ve always done it — at the New Muse community center in Bedford-Stuyvesant; in Montclair, New Jersey; at the New School in Manhattan.

A: That’s always what I’ve done and I think that’s why I was put here. And my family has always been that way in the community, and in all communities — like when we used to travel down South to get people to register to vote.

Q: Can you repeat that? You traveled through the South with your family, registering voters? When?

A: That’s when I was a kid. My siblings were older, and they used to take me along with them. Hey, my former partner and my daughter are now making a documentary about me, so I’m going to leave it at that. Because I’ve promised them that certain things will be theirs exclusively. If I say too much, it’s no longer news!

Q: Fair enough. One last question: You always talk about searching for a sound. What does that mean? Is there a certain sound that you hear in your head, and that you’re still pursuing?

A: That’s the only way that the people can recognize Reggie Workman, is to hear a specific sound.

Do you remember during the ‘60s when everybody had a Fender Rhodes and everybody started sounding the same? But when me and my friends — Lee Morgan and the rest of our crowd — when we were sitting around, we’d listen to records and focus on all the instruments, and it was our job to recognize the sound of every pianist. We could tell the difference of Nat Cole and Oscar Peterson. Our job was to be able to recognize people according to their touch, their sound and what they’re transmitting.

You see, there’s something that comes through you when you have developed your being — that you charge your sound with a particular prana, a particular energy that is unique only to yourself. And nobody can sound like that but you, because that is your fiber and your transmission. So I think the sound is one of the most important parts of being a musician.

And working with young people, I find there are many young people in the school who have tremendous ability to play their instruments and learn all the theory, but they haven’t made their own sound. And so I try and help them to discover what that is — so they can feel that this is me, this is the sound I want, this is what I want to develop in my musical career. Somehow they don’t think about their personal input to what they’re doing. They don’t realize that they have their own sound, their own thing to give.

The 2020 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert will take place on Thursday, August 20th from 5-6PM PT. It can be streamed without charge at SFJAZZ.org and arts.gov.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.