April 12, 2021

2021 NEA Jazz Masters: A Q&A with Albert "Tootie" Heath

by Richard Scheinin

Staff writer Richard Scheinin spoke to Albert "Tootie" Heath in advance of the 2021 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert presented by SFJAZZ during which he was honored. Heath passed away on April 3, 2024.

Albert "Tootie" Heath

Drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath has an identifying sound. It’s like a fingerprint.

That’s Tootie daring you to not pat your foot to “My Baby Just Cares for Me” with Nina Simone. That’s Tootie levitating with John Coltrane on “I Hear A Rhapsody.” And that’s Tootie firing up the cosmic grooves of Kawaida, his own album, born of the Black consciousness movement 50 years ago.

Heath grew up in one of the nation’s jazz hotspots — Philadelphia. Remarkably, his family home in South Philly was a hotspot inside the hotspot. His older brothers — bassist Percy Heath and saxophonist Jimmy Heath — were inspirations. Jimmy rehearsed his big band in the dining room: “He had the saxophones one day; like Coltrane would be there,” Tootie recalls, matter-of-factly. “Next day he had the trumpets.”

J.J. Johnson: "Mohawk" from J.J. Inc. (1961) featuring Tootie Heath

After Tootie moved to New York in the late ‘50s, everybody wanted him: J.J. Johnson, Wes Montgomery, Art Farmer. Moving forward a decade, he was the bedrock for groove-based experiments by Herbie Hancock and Yusef Lateef. He toured for years with the Heath Brothers (with Jimmy and Percy) and enjoyed a stint with the Modern Jazz Quartet. And he can play free, too — as he has with Anthony Braxton and Don Cherry. Tootie hears possibilities everywhere: in bebop, free jazz, world music, hip-hop. One of his bands is called The Whole Drum Truth — and that’s what he brings to the bandstand. He brings honesty, intelligence, and good feelings — and if you’ve ever seen Tootie Heath perform, you know he’s as great a raconteur as he is a drummer.

A member of the 2021 class of NEA Jazz Masters — along with Henry Threadgill, Phil Schaap, and Terri Lyne Carrington — Heath, 85, recently got on the phone at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to discuss his many decades in the music. He recalled getting his first drum set (the bass drum came from a firehouse marching band) and seeing Charlie Parker for the first time (Bird opened for Jimmy’s big band in a North Philly ballroom). And he remembered the time his teenage friend Lee Morgan, the trumpeter, introduced him to a then unknown pianist named McCoy Tyner: “Man… I hadn’t ever heard anything like that.”

Amiable, and at times self-deprecating, he spoke for a good 90 minutes, telling his stories. Asked what sort of message he now tries to impart to younger musicians, he said, “I don’t have a message. I just be myself and try to influence the best I can by being who I am and playing what I can play. That’s it. That’s all I can do… I’ve got to be coming from the heart.”

Albert "Tootie" Heath with Ethan Iverson and Ben Street at the Village Vanguard (photo by John Rogers)

Q: You’ve played with Coltrane, J.J. Johnson, and Dexter Gordon — and also with Anthony Braxton, Don Cherry, and Roscoe Mitchell. You can play bebop, you can play free. How did you get to be so open-minded, musically speaking?

A: I can’t say exactly, but I was not afraid to explore with Braxton or the others you mention. I had a chance to stretch out and be as experimental as possible.

Q: You enjoyed that?

A: I love it. It loosened me up to a degree that I couldn’t do with Dexter or the more traditional guys.

Anthony Braxton: "Marshmallow" from In the Tradition (1974) featuring Tootie Heath

Q: What is the role of the drum — and who are some drummers you admire?

A: Billy Higgins, of course. He was very adventurous and could basically play with anybody — with Dexter or with Ornette (Coleman). Billy Higgins was a specialist at keeping time. So he would establish a beat and continue the rhythm through the whole piece, which is important because the drummer — if you don’t keep a beat, you lose the audience. Because they have to relate to something. If there’s too many notes going by, too much improvising, and you don’t keep some kind of steady rhythm, you can lose them.

So that’s why Latin music is so well accepted, because they keep the same rhythm from the time they start to the end of the piece, usually. R&B is like that. Hip-hop is like that. When you look at the different genres, you see why the drums are so important. And Higgins had that concept of keeping it steady. Kenny Clark had that concept. Max Roach had it, too. And I had a long conversation yesterday with another friend of mine, Louis Hayes, from Detroit, who also played very consistently, and he has a wonderful beat. These are some of the guys that were able to continue the continuous rhythm through a piece. Regardless of how busy the piece was and how many changes were there, they could kind of hypnotize you with the rhythm.

Q: Is that what you do?

A: From the start of the piece, I try to identify the rhythm of the music and try to continue that through it.

Q: How old were you when you started on drums?

A: I was maybe 16, and I wanted to be in the high school band. Some of the drummers graduated that year, so that’s how I got a drum chair in the high school band.

Q: Do you remember your first set of drums?

A: The fire department was around the corner, and my brother-in-law — his name was Octavius Reed — was a fireman, and he gave me a bass drum. They kept it in a closet somewhere in the firehouse; it was a marching band bass drum. And then my father bought me a drum kit from a local music store and it probably cost him a couple hundred dollars. So I had a snare, a couple of cymbals, and the bass drum. I had enough equipment to do a performance.

Q: Did you play along with records?

A: Yeah, like Kenny Clarke and Max Roach and people like that.

Q: Tell me about growing up in South Philly. What was the neighborhood music scene like?

A: South Philly was a very special place. My brother Jimmy was quite a composer and big band arranger. So he had big band rehearsals in my mom’s house in the dining room, right on the table — all the parts would be on the table. He had the saxophones one day; like Coltrane would be there. Next day he had the trumpets. Next day, the drummer would be there; at that time, it was a guy named Specs Wright, who became one of my teachers.

Q: How old were you when this was going on?

A: Oh, I couldn’t have been more than 11 or 12 years old. And I wasn’t even interested in the music they were playing. My interest came later. I started playing with guys of my generation, like Lee Morgan — well, he was younger. But let me tell you about this guy. Lee Morgan lived in North Philly and I lived in South Philly, so it was quite a distance between us. And Lee’s brother, named Jimmy, used to bring him down to the clubs, and Lee would come in and play the trumpet, and he could play — though he wasn’t really allowed to be in there, because he was a kid and they were serving alcohol.

Lee Morgan (photo by Francis Wolff)

And it was Lee Morgan who introduced me to McCoy Tyner. He said, “Man, I want you to hear a piano player.” I said, “OK.” So we get on the trolley car, and we go out to West Philly. And we go into his mother’s beauty salon — McCoy’s mother’s beauty salon. And she said, “He’s in the back.” And he was in the back there, asleep on the couch. And he couldn’t have been more than 12 years old. But there was a piano back there. And man, this guy got up and started playing the piano, and I hadn’t ever heard anything like that — from a kid his age! So that’s how I met McCoy Tyner.

Q: Who was living near you in South Philly?

A: Right around the corner was (pianist) Bobby Timmons, who was raised by his grandfather. I saw Bobby quite a bit, because he got a lot of information about harmony and chords from my brother Jimmy.

So Bobby was right in the neighborhood. And so was a guy named Sam Reed, who played the alto saxophone — he’s still there. And Ted Curson was a trumpet player — he later played with Mingus — who came up with us in South Philadelphia. He lived around the corner from where I was on Federal Street. So Ted lived around the one corner, and Sam lived around the other way. And Bobby Timmons was around the corner, too, so we had a band right there. We used to play in a private club called the West Indian Club, which was downstairs, and they allowed us to play in there. But it was serving alcohol, and it was late at night — an after-hours place — so we would sneak in there and play.

And right across the street from where I grew up was the (American Legion) Lincoln Post 89. We’d see them rehearsing for the parades once a week; Fridays, I think it was. They would come out in the street and march, and the drummers would be out in the street with the brass — the trumpets, bugles. So I got a chance to hear these guys play and I was influenced by the drummers. And they had a bar in the Lincoln Post, too. And we’d go in and play and they would give us 75 cents sometimes, or a dollar, for six pieces.

Q: Who were some of the other young drummers around town.

A: Oh, Lex Humphries, Mickey Roker — and Ronald Tucker; he died really young. We called him “the flame,” because he dyed his hair red up front. He was a really good drummer, a self-taught guy. Eddie Campbell was another drummer in Philadelphia who ended up moving to Brooklyn and playing with Lucky Thompson. There were quite a few good drummers.

Q: Did you take drum lessons?

A: I’d taken lessons from Specs Wright and from a guy named Ellis Tollin who had a place on Market Street, or it might have been Walnut Street. Ellis used to have a place upstairs where he gave drum lessons. And on Mondays he would have jam sessions and guys like (saxophonist) Billy Root and (drummer) Philly Joe (Jones) — guys like that would come up there and play. And if you were astute enough, you’d learn a lot by watching these professional guys who would have the jam sessions. I couldn’t have been more than 15, 16 years old.

Q: Tell me about playing with Coltrane. That was in Philadelphia?

A: Yeah, I was in two groups with Coltrane. (Bassist) Reggie Workman was in one of them, down on Market Street.

And I was in another group with Coltrane called the Hi-Tones — an organ group with Shirley Scott and a guy named Bill Carney who used to sing and play conga drums and percussion. And I played the regular drums, yeah, and Coltrane played the tenor saxophone in that group.

Q: I’ve heard that you and Coltrane had to lug Shirley Scott’s Wurlitzer organ around — in and out of cars, and up and down the stairs to the clubs?

A: Oh man, we hated it.

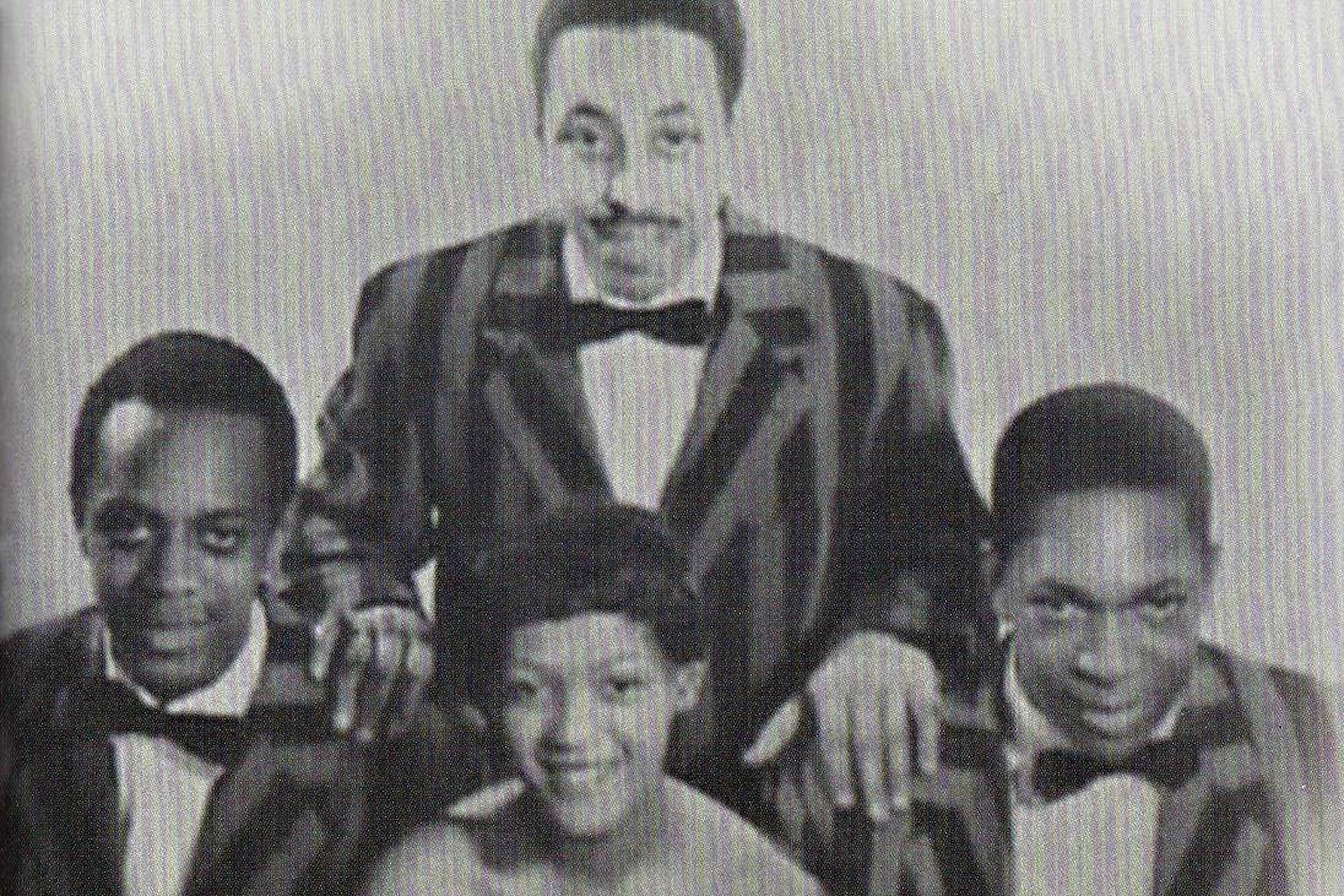

The Hi-Tones: Albert "Tootie" Heath, Bill Carney, Shirley Scott, John Coltrane

Shirley couldn’t have a Hammond B organ, because the Hammond was open at the bottom and guys could stand at the bar and have a straight glance up her dress, you know? So we had a Wurlitzer that had a big piece down in the front — it was super heavy — and two speakers. And we put those two speakers and the organ and the drums and the suitcases with the clothes and all that in a trailer on the back of Bill Carney’s jeep. And John and I would have to carry that organ in and out and up and down.

Coltrane was interesting. Do you know about walking the bar? Horn players would get up there and walk along the bar in the club and blow the saxophone and get the people into a frenzy. And John hated it so much. He would do it, but he would be playing so much saxophone — instead of just honking on the one note required to get people excited. He would be playing so many notes, it was incredible — even then.

Q: You came up with the Coltrane crowd in Philadelphia — also with bassist Jimmy Garrison. (Garrison later played in Coltrane’s classic quartet, as did McCoy Tyner.)

A: Well, Jimmy’s family moved from Florida to Philadelphia when we were in high school and he came to the same school as me. And Jimmy used to come to my brother’s rehearsals. He couldn’t play bass good enough to be in the band at that time — Jimmy was originally a singer, you know. But he used to come and just listen to the music.

Q: Your brother Percy was one of his big inspirations, wasn’t he?

A: He loved Percy. Percy had recorded in New York during that time; it seemed like overnight he was on all the recordings with all the guys that we liked. We realized Percy had something special. So Jimmy Garrison loved Percy, and Percy liked Jimmy Garrison, as well. Jimmy used to listen to all those recordings with Percy, and I think he developed his bass style from that.

And later on, when we were in New York, me and Jimmy had an apartment together in Brooklyn — what they call a cold-water flat. The water was ice cold; I couldn’t take it, so I got out of there.

Q: Before leaving Philadelphia, you played with a bunch of R&B bands, right?

A: Yeah, there was a club in Philadelphia called the Showboat, and that’s where I played with Bull Moose Jackson and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins — all those R&B guys would play in this club, even though it was called a jazz club. I played there with Lester Young, too; I was in the house band.

Screamin' Jay Hawkins

A: No, I had graduated. And I was on my way to New York, but I hadn’t moved yet. I was still trying to get away from my mother and father, you know. They didn’t want me to go, but I was trying to get ready to grow up and be a young man. I was a teenager, like 18, 19 years old.

Anyhow, I had a chance to play with a lot of those R&B guys. I played with some of them down in Atlantic City, too. Sammy Davis’s mother was the bartender in one of the clubs there, and we would see him every now and then. A limousine would pull up in front and it’d be Sammy, going to say hello to his mom.

Q: It seems you were all about music, all the time — listening, playing.

A: That’s true. Jimmy would always have something going on outside of the house with a small group or with his big band. So I would help carry the music stands and help set up in places where I wouldn’t go normally. And that’s where I first saw (drummer) Roy Haynes and Charlie Parker. They were on a bill where my brother had the big band — it was the house band. The opening act was Charlie Parker, and Tommy Potter was on bass, and Roy Haynes was playing drums. Can’t remember the piano player; I know it wasn’t Bud Powell.

This was in a dance hall, a ballroom up there in North Philadelphia somewhere — like a cabaret scene. And if I hadn’t been helping my brother set up the band — put the stands up and set up the microphones and all that — I couldn’t have been in there. I couldn’t have been more than 15, 16 years old.

Q: Who was in your brother’s big band that night?

A: Coltrane was in it. He was playing alto, like Jimmy; two altos. And Calvin Massey played trumpet, I remember, and his cousin Bill Massey was playing trumpet, too.

Q: What was it like for you, hearing Bird as a kid?

A: I didn’t know who he was! I didn’t know he was the guy that everybody was imitating. But he had Roy Haynes in the group, and Roy was special to me, because I was learning how to play drums. I really enjoyed that group. And then my brother came on with the big band after them.

Q: You met so many musicians at a young age, especially through Jimmy. When you got to New York, you must have known everybody on the scene.

A: No, I didn’t know anybody!

Q: Who hired you when you got to New York?

A: Oh, Lou Donaldson. And I played down there at the Village Vanguard for a week with Miriam Makeba. And then I played with Bobby Timmons at the Vanguard. We made some recordings down there with Ron Carter. (In 1961, they recorded Timmons’ classic trio album In Person at the Vanguard.)

Bobby Timmons: "Dat Dere" from In Person (1961) featuring Tootie Heath

Then I did some more playing Monday nights at Birdland, which was right off 52nd Street. Monday nights down there I could’ve been with anybody — but not necessarily because they knew me.

Q: Did you have to push your way into situations?

A: No, no. There were always some openings on Monday nights down at Birdland. If you hang around down there, somebody would say, “Man, what are you doing Monday?” And that’s how you would get a gig, just hanging out in the clubs.

Q: You moved to New York in 1958?

A: Yeah, ’58, ’59. When I first came to New York, that’s when I started playing with J.J. Johnson. Elvin Jones was leaving the group and I took his place. And that’s where I met Freddie Hubbard, Clifford Jordan, Tommy Flanagan — they were all in the group. And we traveled around for a few years — went to Chicago, to Detroit, to San Francisco.

Q: Where did you live in New York?

A: I lived in Brooklyn for a while, and then I lived in Harlem. I lived in all the boroughs. I lived with Percy up by the Polo Grounds in the Bronx; he had an apartment up there. Then he moved to a house in Queens, to Springfield Gardens, and I moved with him. He would go out on tour for months with the Modern Jazz Quartet, and I would help his wife June. They had three kids, three boys, so I used to help her with the kids. And at night, I was playing in Manhattan.

For a while I lived on Fifth Street on the Lower East Side; me and Lee Morgan had an apartment. And I remember I came home one night, and the doors were wide open. Lee and Bobby Timmons were staying there; they were with Art Blakey at the time. They had left the doors wide open, and we were lucky, man, that somebody didn’t come in there and take everything we had. That’s when I decided I’m moving out of there — had to get away from those guys, because they were irresponsible, and really, really wild.

Q: That was 1960 or ’61?

A: Sounds right. A few years later, I went to Europe with (pianist and composer) George Russell.

George Russell Sextet: "You Are My Sunshine" from At the Beethoven Hall (1965) featuring Tootie Heath

(Trumpeter) Thad Jones was in the group when I joined, but he couldn’t make the tour, so Don Cherry came in Thad’s place. And I was surprised, man, because Don was quite a musician. He could play all that complicated music that George had written and that Thad had been playing. I was surprised, because Don was known for improvising outside of the structure of music. And when he finished playing George’s written parts, he would be as free as anybody could be.

Q: Years later, you had Don Cherry play on your album Kawaida.

A: I loved Don Cherry. He was one of my favorite players. And I loved Ornette Coleman, so when he and Don were down at the Five Spot — around the time I moved to New York — I was in the club all the time, just listening. I loved Don Cherry’s exploring, his adventure; he was really an explorer of music. And later when I lived in Europe, anywhere I would travel, in the airport you would see Don playing the trumpet with a group of people gathered around him — playing some folk music of that country. He was incredible, man. I got a chance to live in Stockholm around the same time he did.

Tootie Heath: "Maulana" from Kawaida (1970)

Q: How did you land in Stockholm?

A: Well, when George Russell’s band got to Stockholm, this guy asked me if I wanted to be the house drummer at this club called the Golden Circle. I said, “Yeah.” It was a government-paid gig, one of the best gigs I ever had. So I got a chance to play. A lot of guys came over who were in Europe already: Dexter, Hank Mobley; they would stop in Stockholm and I would be the house drummer. And after a few years, I moved to Denmark — to Copenhagen. And I did the same thing there. That’s when I ended up playing with (pianist) Kenny Drew and (bassist) Niels-Henning (Ørsted Pedersen). We had a trio for some time at this club called the Montmartre. And we played with everybody — I mean everybody: Ben Webster, Don Byas, Coleman Hawkins, Stuff Smith, and Dexter, of course. Dexter was always in there. Johnny Griffin. My brother Jimmy came over and played. And Joe Henderson came and played a week or so.

And then I played a week, maybe two weeks, with Dollar Brand, who you may know as Abdullah Ibrahim, from South Africa. I played a couple of weeks with him at the Montmartre.

Q: You’ve been part of one community of musicians after another. All through your life, every place was a scene, from Philadelphia to Copenhagen.

A: Yeah, well, you know what? I wouldn’t have been in any of those places if I wasn’t playing music. I would never have gone to New York just to walk around; I wouldn’t have gone there. I wouldn’t have gone to Stockholm if I wasn’t with George Russell. And later on (in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s), I wouldn’t have been traveling around with Yusef (Lateef), you know what I mean? Those situations would not have appeared. They wouldn’t have been in my life without the music.

Q: When you look back on your life, is there any one experience that you hold most dear?

A: Yeah, you know the one thing that I love more than all of those groups? I love Yusef Lateef. He was a serious gentleman and a teacher. I learned a lot from him. And I also enjoyed as much to play with Abdullah Ibrahim. I loved that, too. Those two things were the most important things in my life.

Q: Why?

A: Well, Yusef because of him being a gentleman and his dedication to Islam and how he treated us and the opportunities he gave us. When I was moving to Sweden and I told him I had to get out of the group, he told me, “Man, you can go ahead to Sweden. You don’t have to get out of the group. You can come back in the summer and play with me.” Because he was in school during the winter, getting his advanced degrees, and in the summer he would travel. He said, “You can come back in the summer and play with me.” And I appreciated that, man. I was in his arranging class at City College, and it taught me a little bit about writing music. I learned some great stuff from Yusef.

Yusef Lateef: "Nubian Lady" from The Gentle Giant (1972) featuring Tootie Heath

Q: What about Abdullah Ibrahim?

A: Abdullah Ibrahim, his music, I still love it today. I have his albums. I love his music. I love the way he plays without being a jazz musician, and playing a whole lot of notes and things and runs up and down the piano, like most jazz guys do. It becomes a showoff thing of technique now. It’s not from the heart anymore. And his music was from the heart and told stories from South Africa. And so did Yusef. Yusef was trying to tell the stories from Detroit and Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he came from.

You know, people who have a story to tell is what I enjoy — not all the technique that they have and how fast they can do this and how many notes they can play and how many chords. I don’t care about that. That’s not the thing for me. I love the storytelling.

Q: Do you feel that’s what you do when you sit down and play — tell stories?

A: I hope to do it. I hope it’s from my soul and not from no technique. I know I don’t have the technique that most drummers have. So I’ve got to be coming from the heart. Yeah, I’ve got to be doing that — whether I’m conscious of it or not. But that’s where I’m coming from. That’s what I believe in — folk music, music from around the world.

Not necessarily jazz. “Jazz” is a tricky word for me. I like the folk music, the music from all these countries.

Q: When you say “folk music,” does that include Yusef Lateef and Abdullah Ibrahim?

A: I like that. I like the stories that they told in their music. I like Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and the story that he told in his music. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins used to lie down in this casket and sing — sing the blues. I like music that comes from that, and not from a school. I don’t like all that school stuff. It’s too technical. Too much internet business — everything is internet now; chords and changes and all. I like people that tell a story when they play, man.

Let me hear something — Ornette. I love Ornette, because Ornette’s music was from his heart. Not from some school; he wasn’t a college graduate. A guy told Ornette one time — this is funny. A guy told Ornette that he was out of tune — that his horn was out of tune. And Ornette said, “Man, I bought this horn and every note on here is a tune as far as I’m concerned. It’s my horn. Every note on here’s in tune.” And he meant that. And his group — the people that he had; Don Cherry, and (bassist) Charlie Haden and (drummer) Ed Blackwell, and sometimes Billy Higgins. That music was very special to me, because it came from his heart. It was Ornette’s music; I mean, it came from him. And he got those guys to play it with him. It was wonderful. That’s what I thought. That’s why I like guys like Sonny Rollins; he does that, too. He can be very adventurous.

But I like that better than — you know, I don’t have to say names. I like music that comes from the heart.

Q: You have a group called The Whole Drum Truth — just you and three other drummers.

A: Absolutely.

Whole Drum Truth: (L–R) Idris Muhammad, Albert "Tootie" Heath, Louis Hayes, Billy Hart

Q: What does “The Whole Drum Truth” mean to you?

A: It means that we’re telling our story — all of us. That’s our story. That’s what we do when other guys are blowing horns and a bunch of notes and changes and all the things they do with the horns. And singers — I hate jazz singers. I hate to say that, but most of these jazz singers — they need to listen to somebody with a story. Like Billie Holiday had a story she was telling about the people who got lynched, hanging in the trees. People didn’t like hearing that; they didn’t like that story. They didn’t want to hear that. But all that shabba dabba dooby dooby — all that? That’s nonsense, man. You’re making me say things I shouldn’t be saying, but I don’t like singers, other than Dianne Reeves or somebody who’s singing something. Sarah Vaughan I like. All that howlin’ and shabba dobby doo — all that scattin’ and stuff; that’s ridiculous, man. For people to make an art out of that? Oh well.

Q: But you like Dianne Reeves.

A: Dianne Reeves I like, because I like her sound. She has a great singing voice. Yeah, I like her. There’s some other singers, too, but they’re not jazz; they’re not jazz singers. I like that singer from Atlanta — Lizz Wright. Yeah, I love that; now that’s singing to me. No shobba dooby; nowhere near that. Now that’s the kind of singer I like. I mean, she is smooth and wonderful. And the guys playing with her are wonderful. They’re not jazz guys; nobody is playing a whole bunch of notes.

You know, I’m 85, man. I don’t need to hear all that no more. I’m done with that.

Q: You’ve been telling me all these stories from the last 70 years. When you think about your life, does it all seem normal and straightforward — it’s just the way things worked out? Or do you ever scratch your head and wonder, “How the heck did all this happen?”

A: My attitude is that everything I’ve done in my life has been a learning experience for me. There’s nothing that I had the opportunity to do before I did it. Playing the drums with so and so or whatever — it’s all a learning experience. And if I can learn something from it, great. If I can learn something from the conversation we’re having, I’m very pleased with that. Every new situation — it’s an opportunity. That’s how I look at it.

Albert "Tootie" Heath's 2021 NEA Jazz Masters video can be viewed below. The National Endowment for the Arts and SFJAZZ co-presented the ceremony on April 22, 2021.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.