Soul and essence:

The Jazz Photography of Chuck Stewart

June 18, 2021 | by Marcus Crowder

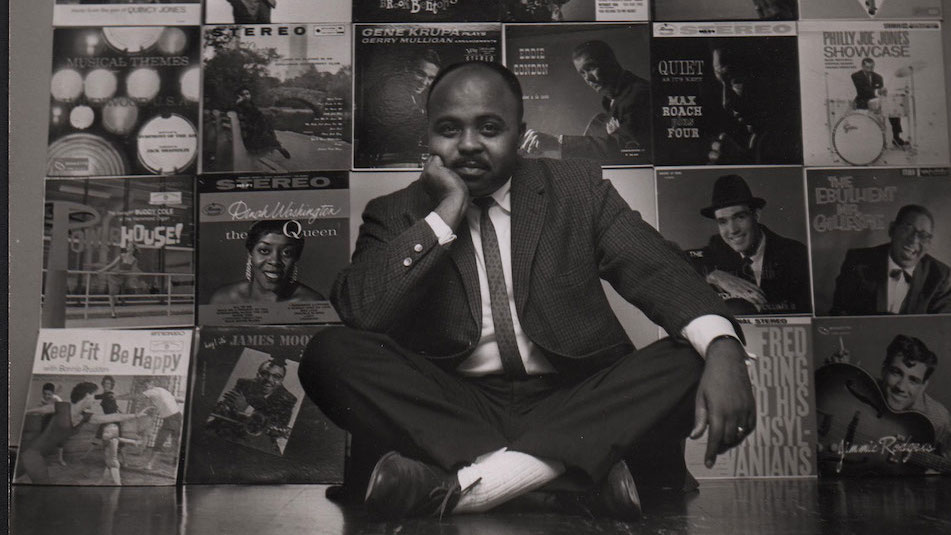

Chuck Stewart (circa 1960)

We have refreshed our public photography installation from legendary photographer Chuck Stewart to help celebrate the start of our 2022-23 Season. The 31 large-scale black-and-white photographs are placed in the outward facing windows of the vacant San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) building across the street from the SFJAZZ Center on Franklin Street at Fell Street in San Francisco’s Hayes Valley neighborhood. Journalist and critic Marcus Crowder tells the story behind the iconic photographer and this newly reprinted installation.

“You know his pictures even if you don’t know his name.” This has been frequently said by way of introducing the late Chuck Stewart’s photography. Alice Coltrane meditatively hovering behind husband John as they listen to a playback of the just recorded A Love Supreme. Young poet Gil Scott-Heron smiling and reclining on the cover of his album Pieces of a Man. An arresting close-up profile portrait of saxophonist Eric Dolphy with his horn. My personal favorite: visceral Betty Carter in full performance mode. These are just a few of the thousands of moments in time captured by Stewart as soon as he had a camera of his own.

Beginning June 19, those images and 27 other rare, little seen photographs from Stewart’s extensive archive will be on display across the street from SFJAZZ in the windows of the abandoned San Francisco Unified School District Building at Fell and Franklin streets. The photos were originally scheduled to go up last year until the pandemic canceled the installation.

Stewart’s exhibit replaces the photos of William Gottlieb. Previous photographers exhibited include Jim Marshall and Stewart’s good friend and mentor Herman Leonard. Stewart will be the first Black photographer shown.

SFJAZZ Executive director Randall Kline, who pushed to get the photos installed on the 19th as a Juneteenth acknowledgement, says, “Looking at it, his work just seems so personal. You feel something more, which is what good art is supposed to do. You feel a bit of personality. He's looking for that.”

Kline considers it a positive cosmic occurrence that Stewart will have his work installed on the nation’s newest holiday celebrating African American’s emancipation from slavery. “The whole thing is, to me, the universe pointing everyone in the right direction,” Kline says. “It’s an amazing catalog when you look at it, and it's so under the radar.”

The photos, printed on synthetic leather, will hang in windows on two sides of the building across the street from the SFJAZZ Center for at least the next year. The upper and middle prints are 91/2 feet high by 6.25 feet wide while the lower prints are 5.75 feet high by 6 feet wide. On the Franklin Street side, the 23 photos include images of Archie Shepp, Joe Henderson, Dinah Washington, Quincy Jones, Anita O’Day, and Yusef Lateef. The eight photos on the Fell Street side include Dave Brubeck, Carmen McRae, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Lester Bowie and Tony Bennett. The photos are taken in several contexts. Some are posed in Stewart’s studio, while others are taken during recording rehearsals or on breaks (he couldn’t shoot during recording because his camera’s shutter would be heard), and at live performances.

Betty Carter, 1968. (Chuck Stewart)

Jazz wasn’t all Stewart did. He worked in many genres, shooting personalities like Frank Sinatra, Eartha Kitt, Bo Diddley, Judy Garland and Janis Joplin. He shot Nina Simone’s first album cover and Gil Scott-Heron’s first two. He shot rock bands as well; the Beatles and Led Zeppelin are both in his files. The photos ended up being used as front covers, back covers, in magazines and frequently in documentary films.

There is origin story mythology around Stewart, who was given a Box Brownie Six-16 camera for his 13th birthday. Kim Stewart, his daughter-in-law and executor of his estate, says he carried the camera with him to his Tucson, Arizona, junior high school the next day and took pictures of Marian Anderson, the great African American contralto, who was visiting. Just the year before, in 1939, Anderson had been denied the opportunity to sing at Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution, who owned the building. Anderson sang in front of an estimated 75,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial instead.

Stewart’s classmates paid 25 cents apiece for photos of the Anderson event and he made two dollars, something of a bonanza during the Depression. A career was born.

Only two U.S. universities offered degree programs in photography at that time. Only one, Ohio University, accepted Black students. Stewart enrolled there and became staff photographer of the school yearbook, also managing the darkroom. In his later career, Stewart was known as a master of photo development and darkroom craft.

In my portraits and improvisational shots, I’ve tried to unveil the soul of the artists I photographed and communicate the essence of their craft.

At Ohio, Stewart met the slightly older fellow photography student Herman Leonard. The two men would become best friends and inexorably linked professionally for the rest of their lives. Leonard’s textured, smoke-filled noirish images of jazz musicians in New York and Paris nightclubs became the genre’s gold standard. Two years ahead of Stewart, Leonard was already a fixture in New York when the younger photographer got there after graduating from Ohio in 1949. Stewart assisted Leonard at his Sullivan Street Greenwich Village studio, hitting the 52nd Street jazz clubs with him at night. When Leonard took an overseas assignment, he left the studio in Stewart’s care. Later, when Leonard moved to Paris, he gave Stewart the keys for good.

In school Stewart was influenced by visiting lecturer photographer Gerda Peterich, who was known for her work with dancers. He and Leonard also worked in the studio of the master Armenian portraitist Yosuf Karsh. Famous Karsh subjects include Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Ernest Hemingway, Audrey Hepburn and Martin Luther King Jr.

Karsh, who developed several innovative lighting techniques, also promoted the idea of getting the right picture at the right time, which inspired Stewart throughout his career. Stewart called it “finding the decisive moment.” Stewart later said that most of what he learned about taking a picture came from Leonard and Karsh. “In my portraits and improvisational shots, I’ve tried to unveil the soul of the artists I photographed and communicate the essence of their craft,” Stewart wrote in his official bio.

It’s not so much that Stewart is unknown but seeing the breadth and expressive originality of his work we understand he should be more known. There are two published collections of his work: the rare, out-of-print Nus de Harlem (nudes) published in 1961 and Chuck Stewart’s Jazz Files, co-written with playwright Paul Carter Harrison in 1985. Stewart could have filled a book of his John Coltrane images alone. To be fair, there could easily be a book of Stewart’s striking photos of Alice Coltrane as well. His stunning cover portrait of her for the album Journey in Satchidananda has become one the iconic jazz images. Their son Ravi Coltrane considers Stewart “the family historian.”

L–R: McCoy Tyner, Archie Shepp, John Coltrane, and producer Bob Thiele during the A Love Supreme sessions, December 1964. (Chuck Stewart)

Stewart shot the extraordinary December 9, 1964 A Love Supreme sessions, though much to his disappointment, the album cover was not his but a photo taken by producer Bob Thiele. Fifty years later, 72 never-printed photographs on six rolls of film from the session were discovered in Stewart’s studio archives. He donated 25 of them to the National Museum of American History, complementing a Coltrane collection that includes the composer’s original manuscript of the music recorded that day. Stewart’s photos are also featured in the It’s Been Said All Along: Voices of Rage, Hope & Empowerment exhibit, which was curated and presented by the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The exhibit exploring social and political commentary by musical artists features Stewart’s photographs of Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, James Brown and Gil Scott-Heron.

Stewart developed an honest rapport with his subjects and in turn, they trusted him. The trust afforded unique opportunities for access and intimacy. Kim Stewart retells a story her father-in-law told her about the famously eccentric pianist and composer Thelonious Monk, “He was shooting at Monk’s apartment and Monk was wearing a yarmulke. Chuck asked him if he could change hats. Monk said, ‘No. I only wear one hat a day. If you want a different hat, you have to come back a different day.’ And he did. And Monk did.”

Though famously modest, Stewart was justifiably proud of his work and sensitive to his legacy.

“If you say Count Basie, a thousand photographers might have photographed him,” Stewart said in a 2016 radio interview. “I want my pictures to say, ‘These pictures are by Chuck Stewart.’ ”

Marcus Crowder is a Northern California-based arts writer and critic.

Originally posted 6/18/21