Ahmad Jamal, Mary Stallings and Zakir Hussain discuss the SFJAZZ Lifetime Achievement Award

January 22, 2019 | by Richard Scheinin

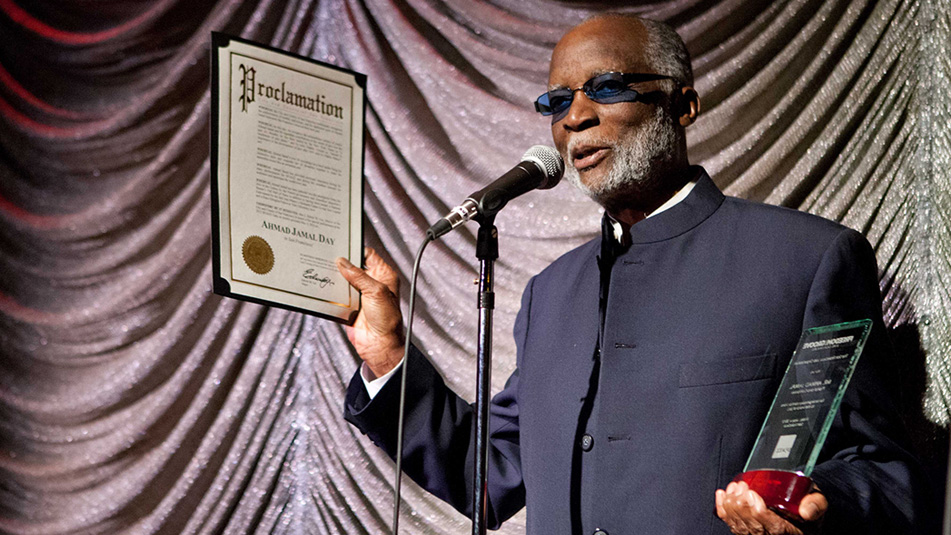

Ahmad Jamal receiving the SFJAZZ Lifetime Achievement Award at the SFJAZZ Gala 2012 themed "Freedom In the Groove"

It started with Tony Bennett. The year was 1992 and SFJAZZ – known back then as “Jazz in the City” – was in a bind. The year before, it had staged several programs designed to put it on the national jazz map: trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie played with a big band; pianist Cecil Taylor performed solo at Grace Cathedral; and conductor Gunther Schuller led a performance of Charles Mingus’s “Epitaph,” a symphony-length work for a 30-piece orchestra. “Suddenly, it was like playing tennis with a better partner,” remembers Randall Kline, the organization’s founder and executive artistic director. Almost as suddenly, he learned that Jazz in the City was operating in the red. What to do? In 1992, its tenth season, more prestige shows were about to be presented – including a night with Bennett at Davies Symphony Hall. Kline came up with an idea: Let’s give Bennett an award, honoring him for his lifetime in music. Moreover, let’s give it to him at a big party attended by major donors. Tony can schmooze. The donors can write checks.

Bennett agreed, and Kline remembers thinking, “Man, I can’t believe we’re doing this.”

It was a turning point. The party turned into an annual event and the award was recognized as more than a good idea. It became a once-a-year chance to salute a great artist who had drawn close to SFJAZZ and its audience. As the organization gained traction – and eventually built its own concert hall – the party turned into a red-carpet Gala event, a lot like the annual Gala concerts staged by the San Francisco Symphony and the San Francisco Opera. Without question, SFJAZZ was now on the map. Every year, the honoree – winner of what came to be known as the Lifetime Achievement Award – would perform with handpicked guests. And over the years, the list of honorees grew to include many of the essential figures in jazz and creative music: Dave Brubeck, Wayne Shorter, McCoy Tyner, Bobby Hutcherson, Ahmad Jamal, Herbie Hancock, Joni Mitchell. Hearing all those names, Kline gets reflective: “The fact that Wayne said ‘yes’ or that anyone said ‘yes’ – I’m still amazed. I mean, it’s not the Academy Awards, but it’s meaningful. It feels right to give a Lifetime Achievement Award to people who have literally given a lifetime to this music and struggled to push the art form ahead. It’s like we’re saying, ‘Thank you. You are family. This place couldn’t exist without you.’”

As SFJAZZ prepares to honor the Cuban pianist Chucho Valdés with its 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award, we decided to speak with him and several past winners. Valdes, who has performed many times in San Francisco over the past 25 years, says the award “has caused me to go back over my life and work, much like looking at an album of old photographs, when you situate yourself in time and place and look back on the decades of your journey. You say to yourself, ‘It was so worthwhile,’ even though you had to work hard, you studied, or you may have had challenges. But always moving forward.”

Our interview with Valdés kept touching on the subject of musical lineage: the fact that he was mentored in Havana by his father, the legendary pianist Bebo Valdés, and that his dad was a close friend of the composer Ernesto Lucuona, whose canon is synonymous with Cuba’s pianística tradition. One’s artistic life, Valdés told us, springs from a deep well. Source materials bubble up to be absorbed, changed and passed along to the next generation: The jazz tradition, in other words, is always in transition. That concept has become a kind of mantra for SFJAZZ – and for Valdés, whose band Irakere has been a breeding ground for new talents since the 1970s. And so we took it up in our conversations with three past winners of the Lifetime Achievement Award: pianist Ahmad Jamal (honored in 2012), singer Mary Stallings (2011) and percussionist Zakir Hussain (2017). Each had a lot to say about tradition and the workings of the creative impulse.

AHMAD JAMAL

The pianist, who will bring his band to SFJAZZ next season for four nights, notes that “Chucho comes from one of the most important places, musically speaking: Havana. But I come from an important place, too: Pittsburgh! Pittsburgh is second to none,” he declares, and rolls out his supporting argument. “I came up in a high school – George Westinghouse High School – where Erroll Garner and Dodo Marmarosa also went to school, and so did Mary Lou Williams. Isn’t that something? Billy Strayhorn was from my neighborhood, and there was a little tap dancer known as Gene Kelly who lived nearby; maybe you’ve heard of him. And then there was Mary Cardwell Dawson, my teacher, who started the first African-American opera company. You see, we had an array of talent coming out of Pittsburgh, starting with Earl Hines, but don’t forget about Art Blakey, and later there was George Benson, Stanley Turrentine and his brother Tommy. It goes on and on; I can’t finish the list. That’s where I got all my stuff from.”

Ahmad Jamal, at age 87, performing in Davies Symphony Hall during the 36th Annual San Francisco Jazz Festival in 2017 (Photo by Ronald Davis)

Jamal’s list includes some of the seminal figures in African-American music in the last century. All got their start in Pittsburgh, where, he says, “We didn’t have that separation of church and state: You had to study Beethoven and Bach, Duke Ellington and Art Tatum. You had to study both worlds, the European classical music as well as the American classical music, which some people call `jazz.’” Growing up, he performed with symphony orchestras, big bands, a variety of ensembles. It’s often said that Jamal’s conception – as pianist, bandleader and composer – is orchestral: “That’s because I grew up orchestrally,” he explains. “I played with so many orchestras in Pittsburgh, so I always maintained an orchestra in my head. That’s why I don’t like to refer to my group as a `trio.’ I like `ensemble,’ because I’ve played with ensembles all my life.”

Just as Chucho Valdés calls his father, Bebo Valdés, “the fountain” from which his own musical life flowed, Jamal credits pianist Garner as the critical source of his own musical approach: “They don’t come any more orchestrated than Erroll!” he says. “He’s an orchestra within himself. He was my biggest influence. Art Tatum was a big influence; I met him when I was 14.” Tatum called the young pianist a “coming great.” But “Erroll, he was from my home town. He was my hero.”

In the 1950s, Jamal and his trio established a unique approach. The pianist wasn't a busy player; he left space around his notes. (Miles Davis noticed and became one of Jamal’s champions.) Jamal was about timbre, touch and, again, the “orchestration” of a performance, involving careful changes in tempo and dynamics. There was a sense of architecture about the group’s improvisations, in its control of ebb and flow, tension and release. Audiences loved it: The pianist’s At the Pershing LP was a hit, and Jamal, now 88 years old, has become one of the most sampled artists in popular music. Hip-hop producers love his time, his feel, his hooks – and borrow liberally from his old recordings. “I was just talking to my lawyer about it,” he says. “The problem is, how do you collect?”

Like Valdés, Jamal is a one-person “tradition in transition.” How does he feel about having won a Lifetime Achievement Award? “It’s quite interesting,” he says, “but I try not to look backwards. I go forward: What’s next?” He is anticipating his four nights next season at the SFJAZZ Center and is even thinking of recording the performances: “That’s a hall, it’s not a nightclub. It’s a jewel,” he says. “We should have more of those around the country: Louis Armstrong Centers and Ella Fitzgerald Centers. That hall is a tribute to the monumental power of this music.”

MARY STALLINGS

Valdes credits Havana, Jamal cites Pittsburgh, and Stallings gives tribute to San Francisco. The singer grew up in the city’s Laurel Heights neighborhood – her house was exactly 1.6 miles from where the SFJAZZ Center now stands. Sitting on the porch at 2327 Post Street, Mary would greet Johnny Mathis, who lived up the block. In her living room, her uncle Orlando Stallings – a saxophonist who taught her to sing “Oop Bop Sh’ Bam” – would rehearse his band, some of whose members toured with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. “There was all this richness around me,” she says. “You walk down the street and there’s music everywhere, music coming out of every house. You’d walk around the corner and there’d be jazz and blues.”

Kamala Harris and Lou Gossett Jr. present Mary Stallings (accompanied by Bobby Hutcherson) the SFJAZZ Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011

She met the blues singer Sugar Pie DeSanto, who went on to sing with Johnny Otis and James Brown. DeSanto lived next door to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on Geary Street, which Stallings attended with her parents and 10 siblings. It’s where Stallings, at age seven, first recognized the power of music, while listening to a group of singers visiting from Chicago: “I was seated upstairs, 6 o’clock in the evening, and I remember listening to the music, looking down and something hit me. You can’t separate the music from the religious aspect, the spiritual aspect. And when I came home, I told my mother, `Mama, I want to be a singer.’”

By age 15, Stallings was a professional, performing with top local bands, though only earning $10 or $15 per gig. She wore gowns sewn by her mother, but Stallings “wasn’t conscious of the struggles; you’re living it.” When she was 16, she began sitting in at the Black Hawk nightclub, where she got to know Dizzy Gillespie, Barney Kessel, Sonny Stitt – “the nurturers,” she calls them and all the others who brought her along. As her career took off, she shared bills with Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald. She sang duets with Billy Eckstine, her idol.

“There’s been a whole lot of life,” she says, and to this day – about to turn 80, she has just recorded a new album – she feels like “that same funny little kid” who was touched in church. She would like every note she sings to “feel warmer than the one before.” That’s the goal of her lifetime in music, and, when she succeeds, that is her achievement: “You don’t think in terms of getting applause or accolades or some kind of award – and when you do get those things, you don’t take it lightly,” she says. Finishing up a weeklong residency at the SFJAZZ Center in 2017, she sang “I Want to Talk About You,” Eckstine’s signature song. Her audience was stone silent, captured by Stallings, who seemed to be singing her life. “You do it from your soul and from your heart, and with the hope that you are connecting with somebody,” she explains. “I look at the faces; am I touching them?”

ZAKIR HUSSAIN

Growing up in Mumbai, India, Hussain had an impressive teacher. His father – Alla Rakha, the tabla master who performed for many years with Ravi Shankar – trained him in the Hindustani classical tradition, waking him at 2:30 a.m. to practice and analyze rhythms. In the morning, Zakir would go to the madrasa to memorize the Koran. Then it was off to Catholic school, singing hymns in the afternoon. Music was part of the flow of daily living – “my buddy, my companion,” he calls it. “Nobody was saying, `This is a tradition that’s 3,000 years old and you must practice 15 hours a day.’ There was an ambiance of normalcy that made it fun, something to look forward to, never work or a chore. And that’s how it’s been all my life.”

Tribute film by Anisa Qureshi (daughter of Zakir Hussain) for his SFJAZZ Lifetime Achievement Award

Hussain became the next link in the chain, himself a master of the Indian hand drums. His approach to rhythm and music-making is so organic and freely creative that it masks the complexity of what he is doing: He can make his drums sound like the beating of wings, like pattering raindrops or deep underwater va-rooms. When Hussain, at age 20, moved to Marin County in 1971, he quickly entered into all sorts of collaborations: with sarod master Ali Akbar Khan, with Jerry Garcia and Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead, with David Crosby and Carlos Santana. By the mid-‘70s, he was on tour with John McLaughlin and Shakti, working out what many described as a new brand of Indo-jazz fusion. Since the 1980s, Hussain often has headlined at SFJAZZ, which has presented him in duo settings with numerous saxophone innovators: Pharoah Sanders, Joe Henderson, Charles Lloyd, Joshua Redman. Always, Hussain says, he tries to “consider the blank slate,” to build something new from scratch. You listen. You respond. Music is a form of conversation; that’s one of the underlying lessons he carries from the tradition in which he was raised. If one is open to the conversation, then the possibilities multiply. Music becomes “one land,” he says, one big expanding tradition.

Considering the Lifetime Achievement Award he won two years ago, he says, “I have a tough time trying to wrap my head around the idea that what I have done is so significant. I look back on my journey, on playing with Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi (Shankar) and John McLaughlin and Charles Lloyd – I am the lucky one. The only way for me to understand this kind of award is that my peers look at me and see that I’m a work in progress… that I’m on the right path. It’s not the pinnacle of any achievement. I’m just trying to get better at what I do.” With that in mind, Hussain, 67, has several new projects, including recordings with three different trios: one with Lloyd and drummer Eric Harland; another with saxophonist Chris Potter and bassist Dave Holland; a third with classical bassist Edgar Meyer and banjoist Bela Fleck. In February, he goes to England to perform Peshkar – his own composition, a concerto for tabla – with the Symphony Orchestra of India.

Mickey Hart toasting Zakir Hussain before giving him the SFJAZZ Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017

Asked to reflect on the tradition from which he emerged, Hussain politely objects: “I would rather not emerge from it,” he says. “I would rather just be engulfed by it. This is such an important part of my metabolism – it’s my DNA that has been part of me since I was three years old. And yes, I try to pass all that on, everything learned from the gurus and teachers, but always by taking the next step or turning the next corner. It has to be spoken in the language of the time and when that happens it’s going to make sense to the people now. I feel that’s what’s happening in my life. It’s a great comfort to have this wrapped around me -- lying in bed at night and feeling that I’m part of this great amoeba that is throbbing and thriving and revealing itself, bit by bit.”

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.