ECM Records:

Curating A New World Of Music

October 16, 2019 | by Richard Scheinin

Manfred Eicher

The best-selling jazz albums are sometimes the best jazz albums – prototypes, showing the way ahead. Kind of Blue by Miles Davis has sold millions of copies since its release by Columbia Records in 1959. Ditto for John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, released by Impulse! Records in 1965.

And then there’s Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert, issued by ECM Records in 1975. Manfred Eicher, the label’s founder, was warned against releasing the disc: Who would buy a double album of solo piano music? At the time, the idea seemed crazy; there was no market for such a thing. But Eicher typically plays his hunches, and they’re often correct. Köln Concert has sold nearly four million copies through the decades, and solo piano recordings have become a thing. Recorded at a midnight show at the Opera House in Cologne, Germany, Jarrett’s set was groundbreaking — and became the biggest-selling solo piano album in the history of jazz.

An independent label with an outsized influence, ECM — which celebrates its 50th anniversary with a series of concerts at SFJAZZ (Oct. 24-27) — has issued more than 1600 titles since it was founded in Munich, Germany, in 1969. It reflects the singular vision of Eicher, a classically trained bassist who “switched sides,” as he once put it, to become a producer and recording engineer. Believing he could “do more for the music” by shepherding recordings from start to finish, he developed an aesthetic that has shaped the way millions of people hear music. The sound of an ECM recording is instantly identifiable: spacious, but intimate, taking your ear straight into the music, as if you were sitting in a room with the players, feeling the molecules vibrate as a drummer taps a cymbal or a trumpeter exhales a soft column of air through the bell of his horn. Wadada Leo Smith, the vanguard trumpeter who has recorded for Eicher off and on since the late ‘70s — and who brings his Golden Quintet to SFJAZZ on Oct. 25 — says, “Manfred makes musicians sound better than they’ve ever sounded in their life. There’s no one else that exists like Manfred.”

Just as recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder left his stamp on scores of albums by Coltrane, Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock and many others for the Blue Note, Prestige and Impulse! labels during the 1950s and ‘60s, Eicher has curated his own world of jazz — a unique and personal legacy. From the outset, he once explained, “I wanted to record things with the utmost detail possible, to get a sense of transparency, to get close to the musical structures. At the beginning, we didn’t have a fixed concept, but there were musicians that I really liked. The idea was to approach improvised music with more of a chamber-music sensibility.”

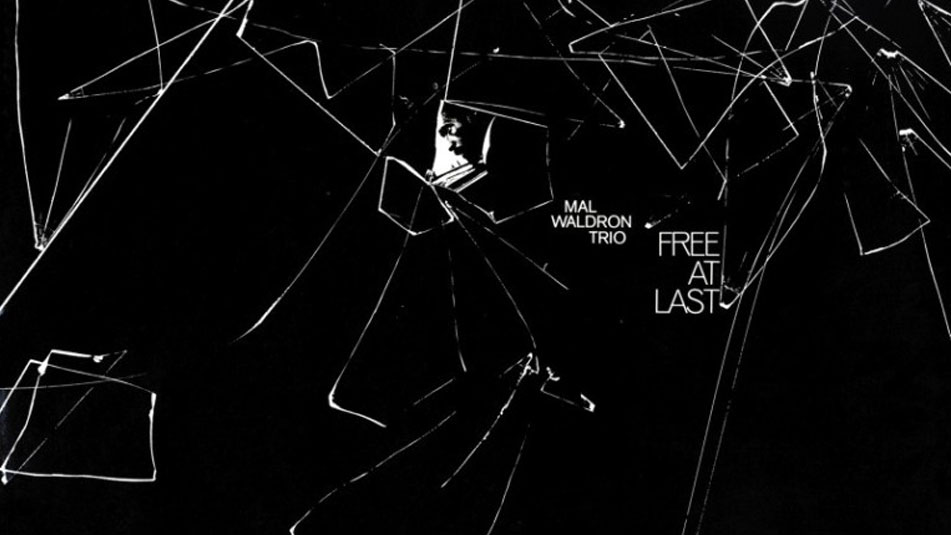

Mal Waldron’s Free at Last

There’s an interesting story behind pianist Mal Waldron’s Free at Last, the first album released by ECM in 1969. Eicher had been working for a mail-order record label — “Jazz By Post” — that operated out of an electronics shop in Munich. Jazz aficionados would stop by to flip through the albums — one of them was Waldron, who was living in Munich and became the first artist signed when ECM was established. Over the years, Eicher kept adding to his roster: Jarrett, Chick Corea and Gary Burton, Carla Bley and Paul Bley, Don Cherry, Dave Holland, Pat Metheny, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Charles Lloyd, Jan Garbarek, Evan Parker, Enrico Rava, Terje Rypdal — the cream of the crop in jazz, in the United States and Europe. Eventually, the label moved beyond jazz to include Gregorian chant and Renaissance music, Bach recitals and contemporary classical music — composers Arvo Pärt, Steve Reich, Meredith Monk — as well as all kinds of trans-cultural and hard-to define experiments. Since signing with ECM in 2013, pianist Vijay Iyer has explored acoustic jazz, electronics, and his own East-West compositions for chamber ensemble and full orchestra. With Eicher’s encouragement, he has publically reinvented himself: “I’d been running around in the jazz business for years. But Manfred doesn’t deal with genres,” says Iyer, who performs with his trio at SFJAZZ on Oct. 26. “It’s just this music he believes in.”

At a time when the recording industry is struggling, ECM — the acronym stands for Edition of Contemporary Music — is an anomaly. It’s a label that avoids the corporate game, content to hit on the occasional best-seller, while doing its own thing — and staying current, making its entire catalogue available for streaming. A friend of Jean-Luc Godard, Eicher, 76, has likened his job as producer to that of an auteur filmmaker. His hands-on, soup-to-nuts approach involves signing the musicians, positioning the microphones in the studio, and supervising the various aspects of post-production: mixing, editing, and sequencing the tracks on the completed album. Musicians say he moves quickly, instinctively: “He gets a feel and then just acts on intuition and, for me, it works,” says bassist Larry Grenadier, who will perform music from his recent ECM album, The Gleaners, at SFJAZZ on Oct. 25. “It’s kind of jazzy in a way, reacting to the moment: BOOM! 'That’s the direction we’re going in,’ and — boom! — it works.” The process extends to curating the abstract illustrations and dreamscape photos that grace the covers of ECM releases. The subject of gallery shows and museum exhibits, they are a “metaphoric translation” of the music, Eicher says. In other words, the look of an ECM album is a clue to the sound inside the package — “the most beautiful sound next to silence,” as Coda, the jazz journal, once put it.

We talked to four ECM artists — Smith, Iyer, Grenadier and trumpeter Ralph Alessi — about their experiences with the label, and about their upcoming performances at SFJAZZ.

WADADA LEO SMITH (Oct. 25, Miner Auditorium at SFJAZZ Center)

Since the 1960s, the trumpeter has been intrigued by the power of pure sound. An early member of the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) in Chicago, he is concerned with “the psychological effect of the music. I seek to find those notes, pitches, sounds that together raise the level of emotional awareness — like an arc or a rainbow, so it has this quality of carrying a musical message.”

Within the AACM, he found musical partners whose goals mirrored his own: saxophonists Anthony Braxton and Roscoe Mitchell, pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, violinist Leroy Jenkins. For 50 years, he has had another partner in Eicher: “Manfred is into a whole ‘nother dimension of sound,” Smith says.

Wadada Leo Smith

They met around 1969-‘70 while touring Germany — Eicher was the bassist — with a band led by saxophonist Marion Brown. In 1977, Smith recorded his album Divine Love for ECM, and you can hear the rainbow emerging: gongs and jangling bells amid great silences and the rush of air through a trumpet or alto flute. The recording “may be the beginning of the real ECM sound,” Smith asserts, “and why is that? That’s because Manfred, as an artist, as a bass player, had gone through the conservatory and then switched his energy to this psychic area of dealing with sound — how sound should be represented and recorded, his whole aesthetic. He was the first record guy to do that, the first record label owner who knows the studio better than any engineer — knows this concept of acoustics and how it plays out in a confined space.”

Smith, 77, is an independent. He tours the world. He holes up at home in Connecticut. He nurtures ideas and projects, often without much fanfare — though he was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in music a few years ago. Every now and then, he returns to ECM, his lodestone. In 1992, he recalls, “I sat down and sent Manfred a shorthand written note on a beautiful postcard,” proposing a solo album for the label. “He answered immediately, saying, 'Let’s do it.’”

The result was Kulture Jazz, featuring Smith alone, on trumpet, flugelhorn, and an array of percussion instruments, as well as Japanese koto, African thumb piano, harmonica, bamboo flute and vocals. Another 13 years passed, and Smith recorded a duo album with Iyer for ECM: A Cosmic Rhythm with Each Stroke, which merges electronics into the trumpeter’s sound world.

Earlier this year, again for ECM, he recorded his “Apassionata” suite with his Golden Quintet: trumpet, cello, piano, bass and drums. This is the piece he will perform in San Francisco. A collection of short compositions dedicated to figures including Martin Luther King, Jr., Pablo Casals, John Coltrane and the academic Anita Hill, it “deals with love, compassion and tolerance for a greater world,” Smith says. ECM plans to release Smith’s new recording next year.

He describes how Eicher operated in the studio during the session: “First we’d get a bit of the music down, and then he’d come out and make adjustments. My trumpet space was moved to another position. The mic was placed differently on the cello. He turned the piano away from a glass window, because the sound bounces off it and the mic picks up the overtones and that gets into the mix, which is an unwanted quality. He gets involved with what it sounds like from the very beginning. He’s looking to build and perfect a sound as he goes along; he can hear what’s coming next. Manfred does it in real time based on his aesthetics, and it’s better for everybody. It frees the artist to make the music match his imagination.”

VIJAY IYER (October 26, Miner Auditorium at SFJAZZ Center)

In the 1980s, when Iyer attended high school near Rochester, NY, he began to familiarize himself with the jazz piano canon. First there was Wynton Kelly and Herbie Hancock. Iyer’s piano teacher, a jazz player named Andy Calabrese, also turned him onto Keith Jarrett’s trio album Standards, Vol. 1, on ECM. Then Iyer started taking albums out of the local library and — now that he looks back on it — a lot of ECM albums came to the fore. He remembers branching out, listening to guitarist Pat Metheny’s Rejoicing, bassist Dave Holland’s Seeds of Time, and other titles “by Jack DeJohnette, Don Cherry, Wadada, Lester Bowie, the Art Ensemble; love the Art Ensemble. There was this whole creative music movement that was pretty well documented by ECM,” Iyer says. “Often when people think of ECM, they think of something else… something more on the ambient side like Crystal Silence (by Corea and Burton) or Jan Garbarek and all these European musicians. But for me, Wadada and that side of things — that was the core of it.”

Years would pass before Iyer — who turns 48 the day of his San Francisco performance —recognized anything particular about the sound of the recordings. In fact, it was only last winter “when my mother-in-law was visiting for the holidays,” he says, “and she likes to have music on all the time. So she said, 'Let’s hear some of your music.’” Iyer, who has recorded six albums for ECM, played two of them for her, including the vinyl version of his Break Stuff trio date: “And I was actually kind of stunned, because it brought me back to hearing the sound of that first Jarrett trio album. I suddenly realized that, audio-wise, there was a family resemblance. I was almost having this out-of-body experience, hearing myself in this other framework. It finally connected with me in the same way that I’d connected with Keith. And this was barely a year ago; I finally realized, `Wow, this is that.’”

He belonged to Eicher World.

Manfred Eicher and Vijay Iyer

How had it happened? Late in 2012, Iyer — who had 17 albums as a leader under his belt — was looking for a new label. He’d noticed that ECM was busy signing young or mid-career players from the New York jazz scene: the saxophonist Chris Potter, the pianists Craig Taborn and David Virelles, the trumpeter Ralph Alessi. “It was kind of time to re-up,” Iyer says, “and I thought, 'Well, why don’t we just give them a call?’ And they answered in like 15 minutes. It was just the right moment.”

The brainstorming began.

He sent Eicher “a whole bunch of projects I had — live recordings of different projects that were underway. And he sat with them for a while, and one day he said, 'We’re going to start with this piano quintet material, because it will set you apart as a composer in a way that hasn’t happened before.’” This was the genesis of Mutations, Iyer’s 2014 debut on the label, for which he composed music for piano, electronics and string quartet. Iyer felt liberated: “I’d never had that opportunity. I could have a project like Mutations or Radhe Radhe” — his East-West orchestral film soundtrack — “or I could record the trio or the sextet. I could do something with Wadada or Craig” — he has recorded duo albums with both Smith and Taborn — and they all could kind of exist in the same universe, and nobody gets mad at me.”

Having recorded six distinctive albums for ECM — he plans to record a seventh this winter — he can describe the recording quality that connects them: “There’s this luminosity and this unified sound, the way it all kind of glues together. A lot of the stuff works under your skin; you don’t want the production to call attention to itself. You just want it to subtly envelop you. Over the years, I’ve heard Manfred say, 'I want people to feel that they’re in a place.’ It’s subliminal; that’s what the reverb is doing in there. It’s subtle. It helps bring you into a space. It makes you feel you’re somewhere.”

But can there ever be too much of the ECM sound? Too much reverb, too much whooshing of breath, too much silence between the notes? How would John Coltrane and Elvin Jones have fared in Eicher’s studio?

“That’s a good question,” Iyer says. “The fact is, I’ve heard a lot of wild stuff on ECM. I don’t know if you’ve heard that George Adams album (Sound Suggestions) — or some of the stuff with Roscoe (Mitchell) is blazingly intense, as is Jack DeJohnette’s Made in Chicago record from a few years back. I don’t think there is one ECM sound, honestly. I think Manfred has a certain personality as a producer, but there’s a lot of versatility to it… He’s just sort of used to experimenting in the studio. He has all these stories about working with Godard, doing all these experimental film scores. He’s fearless. I remember being in the studio with Wadada. I was setting up and Wadada was warming up, and I had some electronic things with me, and Manfred said 'Okay, can we just hear some sounds, so we can get an idea of what this music sounds like?’ And in that moment, Wadada and I just created this duet that had its own integrity, and that became one of my favorite tracks on the album — and it was the soundcheck! And so with Manfred, it’s sort of like he’ll just roll with it. You build something together.”

RALPH ALESSI (Oct. 27, Joe Henderson Lab at SFJAZZ Center)

On Imaginary Friends, his latest ECM album, Alessi reunites a band that first performed nearly two decades ago. The group, known as This Against That, includes pianist Andy Milne, bassist Drew Gress and drummer Mark Ferber. Its music is white hot, but stately, which suits the ECM ethos. A virtuoso trumpeter — he comes from a family of accomplished, classical brass players — Alessi toys with timbre and texture, while pushing a bop vocabulary toward something freer. Released earlier this year, the album — with saxophonist Ravi Coltrane as guest on several tracks — has a strong compositional backbone, yet the performances feel unbound.

Alessi, 56, attributes that to Eicher: “There’s an emphasis on spontaneity, and I think that’s part of the ECM sound,” the trumpeter says. “Manfred’s not one who’s going to be that excited about being in the booth when people do two, three or four takes. He’s interested in capturing what’s in the music without running it into the ground.”

Growing up in San Rafael, CA, north of San Francisco, Alessi was immersed in classical studies. That shifted in 1983 when, at age 20, he went off to study at the California Institute of the Arts outside Los Angeles. Another student, pianist Dave Ake, was “an ECM aficionado,” Alessi remembers. “He was way into that music, and we spent many hours listening to Keith Jarrett’s Belonging and My Song, on and on. It actually changed the course of how I was hearing music, just by virtue of being his friend, and it probably started with Gnu High by Kenny Wheeler.”

Recorded in 1975, Gnu High pairs trumpeter Wheeler with the quintessential ECM rhythm section: Jarrett, Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette. The record “changed my life,” Alessi says. “Kenny Wheeler’s trumpet playing resonated with me because I came from the classical world and what he did with the instrument reminded me of that training. But he played in an expressive way that provided a profound inspiration. It showed me how I could deal with that kind of background and spin it into something honest. You could say that record is almost the epitome of what ECM represents: the expression, the air in the music, the compositional substance — all the variables that are at the top of Manfred’s priority list.”

Ralph Alessi

In 1996, Alessi played his first ECM session. It was led by pianist Michael Cain, another friend from CalArts, for the album Circa. Eicher couldn’t attend, so it was just Cain, Alessi and saxophonist Peter Epstein at Rainbow Studio in Oslo, where so many ECM recordings have been made. The engineer was Jan Erik Kongshaug, a venerated figure at the label, and the recording was “so easy to do, probably my favorite recording experience of my life,” says Alessi. “We did some experimenting with spoken word things and free improvisation. There was a duo piece that Mike and I played. There was just a flow to making this record that I’ll never forget.”

In 2012, when he recorded Baida, his first date as leader for ECM, Alessi finally met Eicher, who produced and mixed the session — and was hands-on throughout. “He’s the absolute master of sound and his ears are impeccable,” Alessi says. “He’ll often talk about finding space and, as he calls it, `air’ in the music. This impacts the way I play and that simple suggestion slows the music down. I need that kind of feedback from a producer… Manfred is hearing things on a very, very deep level, and is always aware of the minutiae, and knowing how to emphasize and de-emphasize the sound. He can hear the small and big picture of what’s happening. And he’s doing a lot in real time, too,” Alessi says, echoing Wadada Leo Smith’s observation. “By the time you get to the end of the session, there isn’t a lot of mixing to do — because he’s always one step ahead of the way things play out. That’s why the records are done so quickly. Whenever I’ve worked with Manfred, we’re mixing by the second day.”

After a short West Coast tour (including the show in San Francisco) with This Against That and saxophonist Jon Irabagon, Alessi will turn to his next ECM project. He’s planning a trio date with pianist Florian Weber and drummer Dan Weiss, and he expects to feel what he always feels when Eicher is producing: “Total freedom. Not that Manfred won’t put his two cents in if he doesn’t feel like things are going in the right direction,” Alessi says. “He’s very good at knowing what’s needed. He’s always part of the music-making with the musicians. I can’t think of another producer who comes close to doing what he does.”

LARRY GRENADIER (Oct. 25, Joe Henderson Lab at SFJAZZ Center)

As a teenager in the Bay Area — he’s from Burlingame, CA, just south of San Francisco — bassist Grenadier listened to “loads of ECM Records: Keith (Jarrett), Dave Holland, Old and New Dreams. Great musicians were recording for that label. But what I really dug was the sound; everything sounded so pure. And as a bass player, it was clear that they were getting some of the best recorded bass sounds, anywhere. And some of that comes from Manfred’s vision of being a bass player himself. But it’s also from his having such a wide perspective in classical music and jazz — and from his basic aesthetic. You can identify that it’s an ECM record just from the sound, which is kind of an amazing feat. I mean, in the old days, I guess you could do that with Blue Note and Impulse!. But for that still to be the case in this day and age — who else is doing that?”

He first recorded for ECM in 1999 with saxophonist Charles Lloyd; it was quite a band, with guitarist John Abercrombie, pianist Brad Mehldau, drummer Billy Higgins and Grenadier. In the years since, the bassist has been in and out of studios with Eicher and various ECM engineers, contributing to sessions with trumpeter Enrico Rava, saxophonist Chris Potter, guitarist Wolfgang Muthspiel, and the collective trio known as Fly, of which Grenadier is a member with saxophonist Mark Turner and drummer Jeff Ballard.

Content to be a sideman — on dozens of sessions for many labels, beginning in the late ‘80s — Grenadier never gave much thought to recording under his own name. But about four years ago, Eicher raised the possibility: “What about a solo album?” he asked.

Grenadier, now 53, says it was “just the right timing. It sounded like a challenge I could use, going into the woodshed and trying to figure out how to do it, and then pulling it off. And if I ever was going to do a solo bass record, it would be for Manfred. I could trust that he would capture the sound of the bass in a way I would appreciate. Also, who else would even put out a solo bass album?” he asks, sounding incredulous. “It’s not exactly something that record companies are jumping to do these days. That’s another thing about Manfred: Even if it’s become a commercial enterprise over the years at ECM, that’s not really what it’s about for him.”

Larry Grenadier

Grenadier was familiar with solo bass albums recorded years ago by Holland and Miroslav Vitous for the label; they acted as reference points during his preparations. In addition, Eicher suggested that he listen to violist Kim Kashkashian’s ECM solo recording of sonatas by Paul Hindemith, from the late 1980s. Grenadier, who had listened to it years before, re-familiarized himself: “It really influenced me, showed me a way of taking a solo stringed instrument and maintaining a thread from piece to piece. It helped me to broaden my thinking about what a solo bass album could be. Is everything through-composed? Do you overdub? Do you layer stuff? I decided, basically, I wanted to do it live; not a lot of overdubs.”

Grenadier spent a year preparing to record The Gleaners; the title refers to the process of gathering information and ideas, and then culling them, gleaning them. “It was a search for a center of sound and timbre, for the threads of harmony and rhythm that formulate the crux of a musical identity,” he has written. Encouraged by Eicher, he began sketching out compositions. He also read a book about the history of the double bass, and discovered that today’s “standard tuning” was preceded by centuries during which bassists used a variety of tunings for the instrument. “It kind of freed me up,” Grenadier says, “and I just started messing around with alternate tunings, looking for what I thought sounded good, so the bass would really resonate for me in a different way — which inspired me to write different material.”

Then came the inevitable: “I spent a lot of time practicing, expanding my technique in order for the music to have as much clarity as possible. I hadn’t practiced that much in a while!”

When he arrived at New York’s Avatar Studios with Eicher and engineer James A. Farber in December 2016, he brought a stack of compositions: a Gershwin standard (“My Man’s Gone Now”), a piece by Coltrane, a piece by his wife Rebecca Martin (the singer-songwriter), and a bunch of his original pieces for pizzicato and arco bass. Once the recording began, Eicher would leave the booth to reposition microphones, moving them closer to the strings, or further away, looking to achieve a “true” and intimate sound — “figuring out as quickly as possible what I was trying to get across,” Grenadier says. He used two different basses with two different kinds of strings on the various tracks, but Eicher’s refinements created a sonic consistency: “It became just one sound on the tape, so it translates to the listener — so anyone who listens to it feels as if they’re actually there in the studio, listening.”

Of course, there is artifice in what Eicher accomplishes: “Even in an ECM situation, I’m not really as freed up as I would be playing for people on a nice stage in a nice sunny room,” Grenadier says. “But Manfred’s experience is so vast. He’s done so many sessions that there is a professionalism about it, and you can relax and react to the music as it’s happening. It’s all very organic. The mix, for example — we did it in four hours, and Manfred shared the credit with me and the engineer (Gerard de Haro), which was nice. It was a very fast process, but fun and democratic.” And then, finally, the time arrived to sequence the 12 tracks: “You can kind of mess up a record if you get the order wrong,” says Grenadier. He credits Eicher with having the natural gut sense for getting the order right.

After nearly four decades as a sideman, making The Gleaners “opened me up to this beautiful idea that you can make a record that’s completely yours, and you can shape every nuance of it,” Grenadier sums up. “So yeah, I’ve been thinking about another project; it kind of changes month-to-month. The thing with Manfred that’s really kind of old-school is, once you’re in, you’re in. If I come to him with another idea, I think he’d probably be cool with it. There’s this kind of a trust. It’s kind of a family.”