Burning Its Way Toward a musical Sweet Spot - Interview with burnt sugar founder greg tate

July 1, 2019 | by Richard Scheinin

Greg Tate

It’s been 20 years since Greg Tate founded Burnt Sugar, the wild-ass mini-orchestra that blasted off from its chief inspirations -- Sun Ra, P-Funk, electric Miles Davis – and burned its way toward a sweet spot. It’s where jazz meets soul meets hip-hop meets Afro-punk; where Duke Ellington and Bad Brains manage to find some common ground. Over four nights at SFJAZZ, the 11-piece band – conducted by Tate, also a guitarist – will overhaul the music of Max Roach (July 11), Prince (July 12), Steely Dan (July 13) and David Bowie (July 14).

Multi-talented Tate, 61, is also one of his generation’s most incisive music critics, a stylist whose sentences spill unpredictably and music-like across the page. A staff writer for the Village Voice from 1987-2003, he has published widely on the arts and politics. His lengthy interviews have included conversations with some of the biggest culture changers of recent decades: Miles Davis, Richard Pryor, Joni Mitchell, Erykah Badu, Chuck D, Wynton Marsalis, Ornette Coleman and his buddy Vernon Reid, the Living Colour guitarist and co-founder (with Tate, singer D.K. Dyson and producer Konda Mason) of the Black Rock Coalition. Also a librettist, author and filmmaker, Tate has argued against “the narrow-minded, essentialized notion of black culture.” For Tate, P-Funk and the Stooges share “sonic connections,” and Burnt Sugar is a reflection of his wide aesthetic palette.

Tate grew up in Dayton, Ohio – “the funk capital of the Midwest,” he calls it, home to the Ohio Players, Zapp, Slave – and Washington, D.C., where he and a friend spun Coltrane sides over their high school intercom system. A freewheeling conversationalist, Tate -- when I called him at his home in Harlem -- touched on subjects as disparate as Elton John and his friend Butch Morris, the late cornetist and conductor. Morris’s “conduction” method – for directing an improvising ensemble with specific hand and baton gestures -- has been adapted by Tate for performances with Burnt Sugar The Arkestra Chamber, as it is officially known. With 16 albums, all but one on its Avant Groidd Musica label, the band is a scene unto itself, its own underground: “Burnt Sugar got the nerve to claim Sly Stone, Morton Feldman, Billie Holiday, Jimi Hendrix and Jean Luc Ponty as progenitors,” Tate has written. “Our player-ranks include known Irish fiddlers, AACM refugees, Afro-punk rejects, unrepentant beboppers, feminist rappers, jitterbugging doowoppers, frankly loud funk-a-teers and rodeo stars of the digital divide.”

Q. Your writing is so unconstrained and free – it’s got some of the vibe of George Clinton or Sun Ra. I’m wondering what you were reading as a kid.

A. A lot of my early reading was science fiction, Marvel Comics and books about various aspects of science, about lasers and masers and submarines and satellites. I was very much a product of the space age, the space race. And then I had an interest in being a comic book illustrator and writer, a storyteller.

And then at about 15, I got the idea that I was going to do a comic book about a trumpet player in the future. And so I went down to the library in Dayton, Ohio, and I took out all these books on music, and that’s where I found Amiri Baraka’s “Black Music.” That’s the book that made me substitute jazz superheroes for Marvel superheroes. Just the names -- Coltrane and Pharoah and Sun Ra – made you feel like these guys were breaking on through to the other side in music.

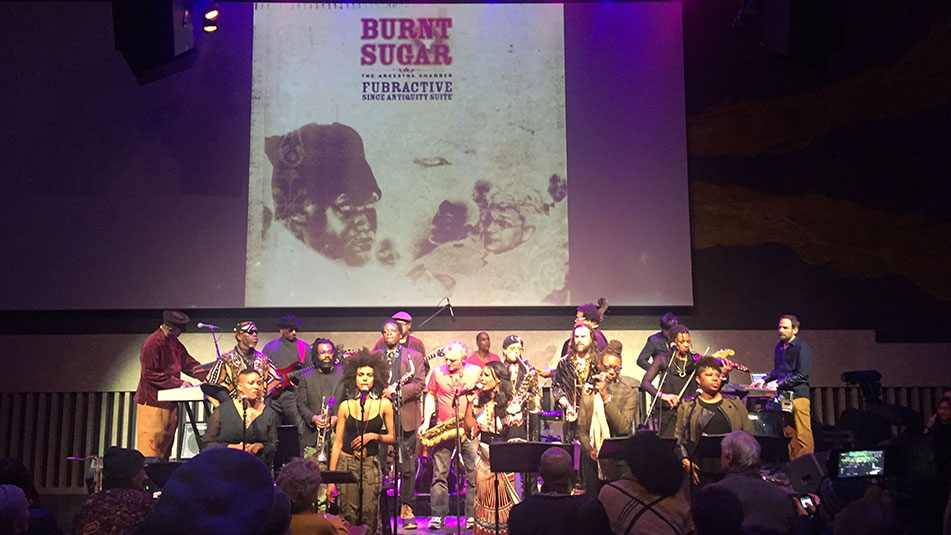

Burnt Sugar

Q. So that’s what you were listening to – Coltrane, Sun Ra?

A. Like a lot of kids my age, my preferred listening was Motown, Sly -- and I really liked the psychedelic Temptations. “Runaway Child” was kind of like my first introduction to musique concrete, you know? In some ways, I was predicting my devotion to what we call “black rock.” But after reading Amiri, I remember I went down to a local record store with the intention of buying some jazz, and they would have the latest records displayed on the wall. And I remember the two records that leaped out at me were “In a Silent Way” (by Miles Davis) and “Thembi” by Pharoah Sanders. And from that moment on, I kind of became a serious music head.

Q. We’re about the same age, and I’m guessing that radio had a big effect on you. I grew up around New York, and the mix of music on the radio at that time was pretty incredible.

A. Definitely, there was a lot of really great radio in Washington, D.C. I remember one station that played a lot of Bowie and Eno and Roxy Music – it was what would be considered a mainstream rock station at that point, but album-oriented. Every time a new Led Zeppelin came out, or a new Stevie Wonder or a new Steely Dan, they were playing it -- whole sides of albums.

And then the Howard University station had this format called “the 360 degrees of the total Black experience in sound,” right? You would hear everything in the same hour: Coltrane and Ellington and Chaka Khan and Marvin Gaye and Sun Ra and Muddy Waters. They were really, really mixing up all of those things, and it had an impact in really giving me a broad aesthetic.

Q. How old were you at this point?

A. At that point, I’m still in high school. And this friend and I, we started doing a radio show playing jazz -- first thing in the morning, over the school intercom system. And somehow one of the major jocks on the Howard station, WHUR, he finds out, and he brings us on, and he starts interviewing us on our musical tastes. We were cracking on the smooth jazz, while praising Dolphy and electric Miles.

Burnt Sugar plays "We Insist! Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite.

Q. You’re painting a picture of the time – the excitement of the music. You were also reading about it in Rolling Stone, right?

A. My mother loved the political writing of Hunter S. Thompson, and she had a subscription to Rolling Stone, which I was reading, every issue. Robert Palmer would be in there – the music critic, who wrote for years for the New York Times. He was a serious devotee of Albert Ayler and Ornette, and I would eat that up. And by the time I got to Howard, in ‘76, I minored in journalism and ended up writing my first pieces for the Howard University Hilltop, which were interviews with Dexter Gordon and Betty Carter. There was so much great music every week at Howard; it was like a musical smorgasbord, and that was my milieu.

Q. Let’s jump to the Village Voice, which was one of the cutting-edge chronicles for music during that period. I remember itching every week – I think it was Wednesday morning – to get my new copy of the Voice at a newsstand on Broadway.

A. Everyone serious about music was reading the Voice, even in D.C. Stanley Crouch was in there, and he was still on the side of the avant-garde at that time. Gary Giddins was in there. And the Voice was covering the punk scene, which had jumped off pretty heavy – my brother was into that. He was into Bad Brains and the Clash and even more obscure bands like Rip Rig + Panic. There were so many great bands in all genres. Reggae was really big. Sun Ra was big. The AACM, the Art Ensemble, all of that.

Then around ’81, my friend Thulani Davis, the poet and novelist, was writing for the Voice, and she told me to send some of my stuff to (Robert) Christgau, who was the chief music critic at the Voice (in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village). So I went to see Nona Hendryx one night; I wrote a review of her at the 9:30 Club, kind of a premier punk club in D.C. And Christgau said he couldn’t use it, but he could use more stuff like that. So that’s when I started writing for him, and in September ’82, I made my move to New York, apartment.

Greg Tate

Q. Your writing has always been different than that of most music critics – the way you punctuate, or choose not to punctuate, and the rhythm of your sentences. It can be kind of torrential, but also playful and really funny. Which writers influenced you during that period?

A. Ishmael Reed was major, and a lot of poets, particularly the great black poets of the period, the Nikki Giovannis and the Clarence Majors and the Sonia Sanchezes. Also, the liner notes that were written by Pedro Bell for Funkadelic’s albums -- those were influential in terms of voice, mixing up poly-syllabics and that kind of thing. That ability to kind of move fluidly between vernacular and more formal critical language – definitely, I got that from Baraka and Ishmael Reed, bringing slang and colloquial phrases at the same time you’re trying to bring your most erudite critical analysis.

It was that mash-up of voice and style.

Q. Explaining the genesis of Burnt Sugar, you once (in 2005) wrote an essay for the Voice titled “Band in My Head.” You said that Toni Morrison and Samuel R. Delany had spoken about writing novels they’d like to read, but couldn’t find. The point of the essay was that with Burnt Sugar, you more or less created the band you wanted to hear, but couldn’t find, correct?

A. That’s it. In the early ‘90s, I’d gotten serious about songwriting and playing guitar, and I put together a band called Women In Love with my cohort Mikel Banks. He saw that I was frustrated with the usual band protocol where you rehearse a bunch of songs and you go out on the circuit and play those songs the way you rehearsed them. There were times when I just wanted to deviate from the program, much to the chagrin of my band mates. So Mikel said to me one time, “The problem is you’ve got enough ideas for five bands.”

So around ’92, I started thinking about putting those five bands into one. Conceptually, the thing that sparked Burnt Sugar into being was – do you know the British music magazine Mojo? Well, they used to do this feature, where they’d ask people, “What’s your favorite album of all time?” And I specifically remember that Ike Turner and Bootsy Collins were featured in that column, and they both had the same answer, which was Rumors by Fleetwood Mac. So I then asked myself the question: “What’s your favorite album of all time?” And (Miles Davis’s) Bitches Brew kind of bubbled up. Now it’s interesting, because if you’d asked me what was my favorite Miles album, acoustically, I would’ve said one thing, and if you’d specifically asked me for my favorite electric Miles album, I would’ve picked one from the ‘70s with (guitarist Pete) Cosey.

But Bitches Brew rose to the surface. It was a song of many parts, with a lot of stop and start; Miles and Teo (Macero, the album’s producer) had actually conducted that album. I saw kind of a connection to my dear friend Butch Morris and his whole conduction scene.

Q. You’ve said that Butch Morris’s conduction techniques became a way of shaking young black jazz musicians out of their “entropy.” You wrote in 2005 that “the jazz being produced by African-American musicians under 45 is genteel and anemic” – that they were stuck in a cul-de sac.

A. I did. And I’d seen Butch do countless conductions, including his first one, around 1982 at the Kitchen. So I was thinking about Butch and Bitches Brew, and I’d just come out of that band situation with Women In Love, and I was thinking about what to do next. And I had the idea of calling on all these great musicians I’m met through the Black Rock Coalition – “Captain” Kirk Douglas (now of the Roots), Bruce Mack, Jared Michael Nickerson (Burnt Sugar’s co-leader) Jason DiMatteo – and I decided to go into the studio with this new project. It was December 1999. We went into the Peter Karl Studios in Brooklyn and I came in with some bass line motifs and we recorded for six straight hours. It was like, let’s do these jams and cut ‘em up and do some overdubs. That was the intention. Two basses, three guitars, three drummers, two keyboardists, a violinist, a vocalist. And we walked out of there with an album.

Q. Burnt Sugar’s first performance followed that same month. It was at CBGB?

A. In the lounge, in CBGB’s basement. It was almost like an after hours joint, a speakeasy kind of spot.

Q. It feels like you intentionally went out and tried to create your own scene with Burnt Sugar.

A. Remember, this was 1999. One of the things that happened, because of the formal straightjacket that Wynton Marsalis’s philosophy had put on the scene, is that the spaces and the opportunities for cats to do much more experimental playing really started to dry up. And the Black Rock Coalition had been around for a good 15 years at this point, and we had made a stand of presenting really powerful, guitar-centric bands with all these powerful players: Vernon Reid, Jean-Paul Bourelly, Dr. Know (of Bad Brains), Ronnie Drayton, Melvin Gibbs. There was this real strong legacy and continuum of guitar-led bands that were playing across genres, and the thing I loved about the Coalition in that period was that all the bands sounded different. There weren’t really any stereotypical ideas about what a black rock band or a black punk band should sound like. But over time, all the clubs and spaces started to dwindle. And at the same time we had this proto-fascist mayor, (Rudy) Giuliani, and he was the reason that a lot of the clubs started to shut down. He revived this ancient law (the New York City Cabaret Law) -- from the ‘20s or ‘30s, from Prohibition -- where they forbid dancing in clubs. Basically, it was like you needed some special kind of license for dancing.

All of that had an impact on experimental musicality. You started to see this diminution of great players that just stretch out. And I just felt like maybe in a band we could create a space for adventurous players to kind of collaborate with each other and just open up the portals again.

Q. In stepped Burnt Sugar.

A. I didn’t want it to be a jam band, per se. But I wanted it to be as open and improvisational as possible. And it seemed to me that Butch had really figured out a way -- with the various gestures and signals -- to do some really precise composing and arranging in ensembles. He brought conducting to free jazz. You could isolate these moments where it became more than everyone’s stream of consciousness going off at the same time.

Q. So, as said, you spoke years ago about the “entropy” of the jazz scene among younger musicians. How would you characterize the scene now?

A. It’s just in the nature of New York’s creative ecosystem that when one path closes, another opens. What happened was another generation of players started to emerge. Vijay (Iyer) is part of that generation, as is Jason Moran -- clearly very open-minded, aesthetically adventurous, multi-disciplinary artists who weren’t necessarily trying to maintain some kind of retrograde idea of jazz. They were very interested in what was going on outside of the acoustic jazz realm. They were interested in hip-hop and dance music. And as things continue to advance, you have another generation of players who are adventurous and don’t care about toeing the line. You’ve got a whole scene going on in London. Closer to home, you’ve got (Robert) Glasper. You’ve got Makaya (McCraven). You’ve got Kamasi (Washington).

L.A. is just banging right now: Kamasi’s crew and Terrace Martin and Kendrick Lamar and Flying Lotus. That’s really where you see the nastiest kind of brew happening among the players, with the ideas coming out of that camp. Because they’re not feeling the shackles; they’re being as bold and brazen as they can be. These cats are just setting their own course in terms of improvisation in the 21st century.

Q. You’ve written about the stereotype of the black intellectual “who operates from a narrow-minded essentialized notion of black culture.”

A. I came up in the era when Elton John’s “Bennie and the Jets” was a major hit on black Top 10 radio. Same thing with Bowie’s “Fame.” The high school I went to in D.C., Coolidge High – it was 99-and-three-quarters black, right? But everybody was into rock, into Zeppelin and Kiss and Bowie. We heard it all as one music. In D.C., it was just about the love of music, man. We loved War and Mandrill and Chaka Khan; all those bands had their own identities. You know, Funkadelic started out in Detroit doing gigs with MC5, the Stooges and Vanilla Fudge. So there are these sonic connections between Sun Ra and P-Funk and the Stooges.

When I was coming up, there wasn’t a segregated palette that was going on. You know what I mean? The (San Francisco) Bay that I remember is the one with Santana and Tower of Power and Pete Escovedo and integrated bands like PG&E. And when people think about the golden age of hip-hop, they think of the audience as being predominantly black and Latin. But the people who really created the hip-hop aesthetic, people like Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa, were into mixing things up. John Bonham had great break beats. Billy Squire had great break beats. If you were to see Bambaataa’s collection, he’s got all of Laurel Canyon up in there and all kinds of ethnic music. Early hip-hop’s community of DJs was much broader in its tastes than folk might imagine.

Burnt Sugar

Q. Let’s talk about Burnt Sugar’s broad palette. How did these repertory shows begin, doing Steely Dan’s music and Bowie’s music, and so on?

A. Around 2010, Melvin Van Peebles, who did Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, asked us to collaborate on a music version of Sweetback that we did in Paris. And when we got back, the Apollo Theater asked us to do kind of a musical theater piece based on James Brown. That’s the point where we bifurcated into this band that started doing these repertory projects.

Q. How did Steely Dan’s music come into the picture?

A. Vernon Reid had approached me -- I want to say around 2004 -- around the notion of Burnt Sugar doing a Steely Dan show. Specifically, he wanted to signify on Steely Dan’s use of black archetypes and characters; there are stereotypes in some of their songs, because they’re kind of the consummate white Negro hipsters, right? So Vernon probably had his own conflict – a deep admiration for Steely Dan’s skill, but they were taking bold liberties with the way they tried to talk about black culture in their songs.

Q. I’ve seen video of Burnt Sugar doing “Black Cow.” It’s intense.

A. One of the things that happened -- because we’ve got some really soulful singers in the band -- is we started paying attention to, yeah, what is the story? “Black Cow” is about the conflict in man-woman relationships, and when you have a black woman singing “Black Cow,” those lyrics take on a whole different kind of poignancy.

In the corner

Of my eye

I saw you in Rudy's

You were very high...

She’s singing about a man who could’ve been a contender, and now he’s living in the bottle. But she goes on:

I can't cry anymore

While you run around

Break away

Just when it

Seems so clear

That it's

Over now

Drink your big black cow

And get out of here.

Now, Donald Fagen singing that, it just sounds like something very abstract and snarky and biting. But when you have a woman singing that about a male character, it becomes a whole other movie, and a whole lot more vivid.

As it turns out, the Steely Dan show -- along with the Bowie show and the James Brown show – are the ones we’ve repeated the most. We did Steely Dan for a couple of nights at Le Poisson Rouge in New York, and a couple of guys from Steely Dan’s studio band came down, like the guitarist Hugh McCracken. So we got to play those tunes in front of some really serious Steely Dan heads, and what a couple of people told us is that our interpretations were so strong that it made it hard to go back to Steely Dan.

I would put Steely Dan in a similar space that I would Bowie in. They were writing amazing music for themselves, but they were also writing amazing songs for R&B singing, whether they intended it or not.

Q. Which Steely Dan tunes will you play at SFJAZZ? (July 13, two shows)

A. We’ll do 10 or 12 songs: “Pretzel Logic,” “Black Cow,” “Deacon Blues,” “Haitian Divorce,” “Kid Charlemagne”…

Q What about Bowie? Which tunes will you play? (July 14, two shows)

A. “Changes,” “Stay,” “Golden Years,” “Fame,” “Let’s Dance,” “Blackstar,” “Breaking Glass,” “Suffragette City.”

Q. And what about Prince? (July 12, two shows)

A. We’ll do “Cream,” “The Beautiful ones,” “Computer Blue,” “Sometimes it Snows in April,” “Condition,” “I Wonder,” “Girls & Boys”...

Q. Do you write the arrangements?

A. The arrangements are actually very collaborative. When we do one of these repertory projects, the band will first go learn the album versions. Because when you work with singers and chord changes and lyrics, the musicians have got to establish their comfort zone first -- before I can come in and start messing it up. And then in the course of our rehearsing, it gets opened up a little bit, and then with the conduction element it gets opened up a little more. But it’s not like every tune is necessarily ripe for conduction. Sometimes I just want to hear the song.

Q. We haven’t discussed Max Roach. In San Francisco, you’re performing his album “We Insist!” (July 11, two shows)

A. I’ve always felt that Max was an under-sung composer, just a great writer. As for the genesis of that material, I was asked to put together a band for the National Black Arts Festival in Atlanta in 1998 – the year before Burnt Sugar came together. And I had this idea to take Max’s music and combine it with drum ‘n’ bass. Now the drummer that I’d worked with in the band Women In Love was Marque Gilmore, who’d been combining digital loops with live drumming. He had moved to London in ’94 or ’95, at the peak of drum ‘n’ bass, and he became known as the only drummer who could keep up with the tempos. So when I got this bright idea to combine Max with drum ‘n’ bass, I called Marque, who then played with us in Atlanta, and we did “We Insist!” and “Percussion Bittersweet” and “It’s Time.” Vernon Reid was on that date, and he did these great versions of “Driva Man” and “Freedom Day,” and I always wanted to return to that music with Burnt Sugar. We actually did it last year at a festival in Sardinia.

Burnt Sugar

Q. I’ve been meaning to ask: Why did you name the band Burnt Sugar?

A. In the early ‘90s, the pianist Geri Allen had approached me about working on a project, and this “Burnt Sugar” idea came up. I was thinking about the Crayola crayons color burnt sienna – it was like a riff on that. But as we got into the project, I realized the name wasn’t as clever as I thought. Because if you google “burnt sugar,” what you get is like a million pages of dessert recipes. It turns out that “burnt sugar” is the go-to term for caramelized desserts.

Still, when you get deeper into this “burnt sugar” idea – it’s about the contrast you get between the raw and the cooked. So when I was putting Burnt Sugar together, I was thinking about how with any kind of improvised music, what you’re looking for is heat. Butch (Morris) talked a lot about heat and conduction and combustion; he carried those qualities over into making the music. And one of the things that I’ve always loved about Miles is the contrast between his lyricism and his fire. As a Miles-head, you loved it when the band’s on fire and up-tempo and driving. But then when Miles slows it down to that quiet fire, that’s the sweet spot, too. So I was thinking about all of that when I named the band Burnt Sugar.

Burnt Sugar performs at SFJAZZ Summer Sessions Concert Series 7/11-7/14.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.