The Sounds of Trinidad: Etienne Charles' Carnival Celebration

February 25, 2018 | by Richard Scheinin

Etienne Charles and "Jab Molassie"

Trumpeter Etienne Charles grew up in Trinidad, where music was everywhere and almost everyone he knew played in a steel band: “Trinidad, it’s a very percussive society, and before you have any other instrument, you beat on stuff,” he says. “In school, you beat on your desk; my first percussion instrument was my desk, and that’s how I started exploring sound.”

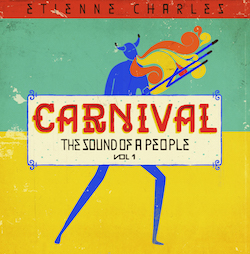

If you’ve paid attention to the jazz scene over the past decade, you know that Charles went on to become one of the most successful young trumpeters in jazz. He recently joined the SFJAZZ Collective and has recorded with his own bands since 2006, always fusing Afro-Caribbean rhythms and folk forms with modern jazz -- and often doubling on percussion. He’ll do it on March 1 at SFJAZZ, when he invites the audience into his pan-Caribbean concept, opening up the dance floor for Carnival: The Sound of a People, which is also the title of his new album. For Charles, Carnival is an “ocean” of folk customs and hybrid elements from across the Caribbean: “It’s music. It’s dance. It’s costume. It’s improvisation. It’s history. It’s social commentary, political commentary. It’s all of that in one word. And the only way to do it in a show is to have as much of it as possible.”

If you’ve paid attention to the jazz scene over the past decade, you know that Charles went on to become one of the most successful young trumpeters in jazz. He recently joined the SFJAZZ Collective and has recorded with his own bands since 2006, always fusing Afro-Caribbean rhythms and folk forms with modern jazz -- and often doubling on percussion. He’ll do it on March 1 at SFJAZZ, when he invites the audience into his pan-Caribbean concept, opening up the dance floor for Carnival: The Sound of a People, which is also the title of his new album. For Charles, Carnival is an “ocean” of folk customs and hybrid elements from across the Caribbean: “It’s music. It’s dance. It’s costume. It’s improvisation. It’s history. It’s social commentary, political commentary. It’s all of that in one word. And the only way to do it in a show is to have as much of it as possible.”

In San Francisco, his band and special guests — traditional Carnival performers from Trinidad, in costume — will spin the audience through the island’s rhythmic history, which is long and ingenious. Since the 1880s, when British colonizers banned the playing of African drums, Trinidadians have improvised a world of rhythm by beating on tuned lengths of bamboo, as well as on biscuit tins, glass bottles, frying pans, hunks of iron (think: car engines and brake hubs) and steel pans fashioned from oil drums – the famous steel pan orchestras associated with calypso and other Trinidadian genres. At SFJAZZ, the quintet – trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass and drums — will interact with field recordings made by Charles in 2016 when he traveled throughout Trinidad, documenting Carnival celebrations. In Claxton Bay, he recorded one of the island’s infectious tamboo bamboo ensembles. In Laventille, known as the birthplace of the steel pan, he recorded the most famous rhythm section in all of Trinidad, an ensemble of virtuoso “iron” players. Videos from his research — funded by a Guggenheim Foundation grant — will be projected onto a screen above the stage in San Francisco, showing “what the streets of Trinidad look like at Carnival time. So it’s an all-inclusive show, because Carnival is an all-inclusive art form.”

Charles, 35, will put special focus on a masked Carnival character known as Jab Molassie, a kind of devil, representing the spirit of “a slave who met with death in a cauldron of boiling molasses — one of the ways in which slaves really did go to their deaths,” he explains. In Trinidad, specific rhythms are associated with Jab Molassie, who dances in the streets at Carnival, smeared with red, green or blue body paint — and breathes fire, ignited by kerosene. “In the folklore, Jab is this spirit returning to life,” Charles says. “Jab can remind you of how brutal humanity can be; when I see a Jab, I see the Middle Passage, I see the suffering, I hear the screams and shouts. But this Jab is also dancing, mimicking, doing it with parody. The music, the rhythm, just leaves people feeling joyful, and I want the whole world to see the magic of this tradition. I want the people of San Francisco to be wowed by the magic of this Jab. It’s still un-codified. It’s still a street art. It’s still purely folk. It hasn’t been put in schools. It’s still raw.”

For the March 1 show in San Francisco (and a second show on March 2 at The Broad Stage in Santa Monica, CA) Charles is flying in a pair of celebrated “Jabs” from Trinidad: Steffano Marcano and Tracey Sankar, who will dance to the music in their Blue Devil garb. Carnival is something Charles has experienced since he was a small boy in the village of Glencoe, in northwest Trinidad, where he joined a steel band, took up the trumpet at age ten, and learned about his family’s pan-Caribbean roots. His great-grandfather on his mother’s side came from Martinique, while his father’s side of the family has strong connections to Haiti.

Figuring out a way to unite the various strands of his musical DNA took a while. As a jazz studies major at Florida State University in Miami, Charles came under the tutelage of pianist Marcus Roberts, who counseled him to hold onto his Caribbean roots while developing his own musical voice. As a trumpeter, Charles came under the sway of Lee Morgan’s recordings, and he began to study the history of jazz trumpet from Louis Armstrong and Harry “Sweets” Edison to Wynton Marsalis. He encountered the albums of a couple of Caribbean-born saxophonists who were making a mark in New York in the early 2000s: David Sánchez and Miguel Zenón, both from Puerto Rico. “They were doing what I wanted to do,” Charles says. “They were using advanced composition techniques on Caribbean folk forms and grooves, applying melody and harmony over traditional rhythms. I used to listen to David’s album Melaza. There’s a bass line on one of those tunes that’s very similar to a Trinidadian bass line, and when I heard that, it clicked. It was the beginning of my realizing that jazz is as Caribbean as it is American. In the combo at Florida State, I was playing all these tunes by David and Miguel, and they became my templates for learning to improvise and compose.”

Interestingly, 15 years later, Charles has now joined Sánchez and Zenón in the horn section of the SFJAZZ Collective. (After 15 seasons, Zenón will retire from the group after its April tour.) And after 15 years, Charles’s way of uniting the various strands of his musical DNA has become like second nature. “Jab Molassie,” the new album’s opening track, builds upwards from a bass line composed by Charles to complement traditional “Jab” rhythms. The harmony flows over the top of the percussion, as does the melody, which conjures eerie and celebratory moods, much like the tune’s devilish namesake.

In San Francisco, Charles will perform “Jab Molassie” — and as many of the album’s other tracks as time allows — with a group of top-tier New York musicians: bassist Reuben Rogers, pianist Sullivan Fortner, guitarist Alex Wintz, saxophonist Godwin Louis and drummer Jamison Ross. Expect the performances to click as the musicians fuse the traditional and the new. A five-part suite titled “Black Echo” is the album’s centerpiece, tracing the evolution of Trinidadian rhythms from tamboo bamboo to iron and steel: “The Creole imagination is a helluva thing,” says Charles. “One door closes and the next door opens.” Clearly, doors keep opening for Charles; listening to the album, you may also catch echoes of electric Miles Davis and hip-hop, calypso and samba, iron and steel. “It’s all black music from around the diaspora,” he says. It all flows from the same ocean of sound, and as Charles dips into it, his aim “is always to uplift people, to take them out of what ever funk they may be in,” he says. “To me, it’s like the beauty of Jab Molassie — the way the character changes from the ordinary to the extraordinary. Their eyes open bigger, they start to scream, they start to breathe fire. That’s what I want to do with my music and with whoever is listening. To take them to this extraordinary place, where they transform.”