2021 NEA JAZZ MASTERS:

A Q&A with Phil Schaap

April 19 2021 | by Richard Scheinin

Phil Schaap in the studio at WKCR radio. (photo by John Abbott)

Concluding a series of conversations with 2021 NEA Jazz Masters, SFJAZZ Staff Writer Richard Scheinin speaks (below) to Phil Schaap, the jazz historian and radio DJ. Schaap is one of this year’s four NEA honorees. In advance of the NEA Jazz Masters Online Tribute Concert on Thurs. April 22, Scheinin already has posted Q&A conversations with 2021 Jazz Masters Henry Threadgill, Albert “Tootie” Heath and Terri Lyne Carrington, as well as with saxophonist Miguel Zenón, the concert’s Music Director. (The show is a co-production with SFJAZZ.)

Phil Schaap is a national institution — a one-man memory bank and support system for jazz. The music is his heart and soul. He approaches it with reverence as he teaches people to listen. That’s what he has done for over 50 years, as a founding jazz radio DJ at New York’s WKCR; as an educator at Juilliard and Princeton; and as a record industry sleuth — discovering and remastering unknown recordings by the likes of Charlie Parker and Ella Fitzgerald. Along the way, he has won six GRAMMY awards for audio engineering, producing, and historical writing.

Musicians have been his teachers — and his friends.

He grew up in Hollis, Queens, a neighborhood that was home to many of New York’s greatest jazz musicians. The son of jazz lovers — father Walter Schaap was a jazz historian and discographer — Phil began knocking on his neighbors’ doors, and that’s how he got to know Buck Clayton, Milt Hinton, and Roy Eldridge. In 1956, while backstage at a jazz festival with his mother, Marjorie Schaap, he met Count Basie’s drummer, Papa Jo Jones. As the story goes, Marjorie told Jones that her five-year-old son was quite the jazz expert. That’s when Jones looked at the child and challenged him: “OK, mister, who’s Prince Robinson?” Phil shot back the answer: “The tenor player with Mckinney’s Cotton Pickers.”

“It’s probably one of the few times I stopped him in his tracks,” Schaap recalls.

Papa Jo Jones soloing with the Jazz at the Philharmonic All-Stars, 1957

Jones became an occasional babysitter — and later, his mentor and pal. Papa Jo explained the music’s secrets and instructed him to “pass it on.” Phil took that to heart. In 1970, at age 18, he began broadcasting on WKCR where his show “Bird Flight” — devoted to the music of Charlie Parker — is heard to this day. For the last 21 years, he has curated at Jazz at Lincoln Center, where he has been Wynton Marsalis’s right-hand man — and founded Swing University, an academy for jazz appreciation.

Known for his flypaper memory, Schaap can tell you anything and everything about Lester Young (the Youngs and the Schaaps were family friends); Eddie Durham (Count Basie’s trombonist-composer and, later, one of Schaap’s closest friends); or Ornette Coleman (at whose funeral Schaap presided). Schaap can famously recite the birthday of any jazz musician under the sun. It’s more than a card trick. As drummer Max Roach once said, “There isn’t anyone in the country who knows more about this music than he… He knows more about us than we know about ourselves.”

His stories are unique — about taking Sun Ra out for ice cream or being challenged to an eating contest by Rahsaan Roland Kirk. (It was a tie.) Phil’s friends remember him lindy-hopping down the aisles of the West End jazz club on Broadway between 113th and 114th Streets. There he arranged gigs for veterans of the Basie and Ellington bands at a time when they seemed to have been forgotten. His devotion to jazz has always been like that — uplifting and driven by a pure love of the music.

One of this year’s NEA Jazz Masters — along with Henry Threadgill, Tootie Heath and Terri Lyne Carrington — Schaap, 70, recently picked up the phone at his home in New York City. We spoke for more than two hours: It was classic Schaap — an accumulating wave of sharp memories and hard data, a bit overwhelming at times.

Phil and I have been friends for nearly 50 years. We met as students at Columbia University in 1972 — at WKCR, the college radio station. Three years older and vastly more knowledgeable than I was, he became both a buddy and a mentor. He introduced me to his friends Doc Cheatham, Cozy Cole, and Tiny Grimes. He ushered me into the world of Charlie Parker: When the WKCR staff presented its first “Bird” Festival from Aug. 29-Sept. 2, 1973, Phil and I held down the final all-night shift. Phil likes to say that KCR “hit the jackpot” with that festival. The musicians who had known Bird were listening: Charles Mingus kept calling the station, commanding us to play a particular track, or berating us for some dumb comment we had made. For five days, you could walk around the city in the 100-degree heat and hear Bird coming out of open windows. Imagine! Parker had been dead for nearly 20 years, but people were listening anew. After we closed out the festival, Phil and I went out for breakfast on Broadway at a dive called the College Inn. Digging into our scrambled eggs, we felt exultant, certain that we’d been involved in a world-changing event.

Interviewing Phil after all these years was a full-circle experience.

At times, it felt melancholy. Fighting cancer since 2018, he was taking stock, listing the musicians at whose funerals he has delivered eulogies: Eddie Durham, Russell Procope, Jo Jones, Lawrence Lucie, Richard Wyands. But he also spoke repeatedly, and with huge pride, about his many students who are carrying his mission forward. And he spoke — at length, believe me — about three of his ongoing research projects, concerning Basie saxophonist Herschel Evans, cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, and a virtually unknown pianist named Garnet Clarke, who died of tuberculosis in an insane asylum at age 22 in 1938. “His story may be fascinating,” Phil said, “but I make the point in the essay: It really shouldn’t be told if it wasn’t of musical value. The fact that someone had a troubled existence 90 years ago — what difference does it make? You’ve got enough people right now with troubled existences. But if he was a great musician — and he was — then his story deserves to be told and remembered. There’s not much of him on record. But what there is — it exists in the present tense. And that’s the point. Garnet Clarke is great. Herschel Evans is great.”

As is Phil Schaap, Jazz Master.

Phil Schaap at WKCR radio, 1991. (photo by John Abbott)

Q: When were you first emotionally touched by music? Can you remember listening to something as a kid and getting goosebumps?

A: Always. As a toddler, or maybe infancy. It was always there.

Q: There are lots of jazz scholars. But you’re different than most. Your connection to the music and the musicians has always been personal.

A: They were my friends — like my expanded family or maybe my second family. I mean, this is jumping ahead, but Eddie Durham was one of my closest friends. We used to drive around together. He would be sleepy after gigs. He had a very nice station wagon, and I would do the driving. He was one of the nicest people I ever met, and he also happened to be a genius.

Q: When you were a kid in Hollis, who lived next door to whom? Describe the neighborhood’s layout.

A: Well, next door to Roy Eldridge is Roy Haynes. And next door to Rev. Gary Davis was Dr. Sohmer, a physician who played the piano. He could play “In a Mist.” Warne Marsh and Lee Konitz were also in the neighborhood. They were living with Lennie Tristano... And it was through Lennie that I met Lee in 1960. It was a concert that Tristano put together at the Hollis Theater on 192nd Street and Jamaica Avenue. That’s 61 years ago. My mother told me to go get the Gottliebs — they lived on 193rd Street — and make them come to the concert. Because my mother said, “There’s got to be more people in the audience than musicians on the stage.”

Q: You’ve told me about Roy Eldridge’s wife inviting you in for milk and cookies. Were Eldridge and Haynes on your block?

A: No, they were on 109th Avenue. It was a mile walk — and I walked.

Q: How old were you when you started knocking on musicians’ doors?

A: I was a child. It was no big deal.

Q: Did Jaki Byard live nearby?

A: Yes, that was later. He lived at Hollis Avenue and 200th Street. You took the Q2 (bus) if you wanted to go see Jaki Byard, a fascinating individual. When you went to his house, you found out how many instruments he could play besides the piano. And he was good on all of them.

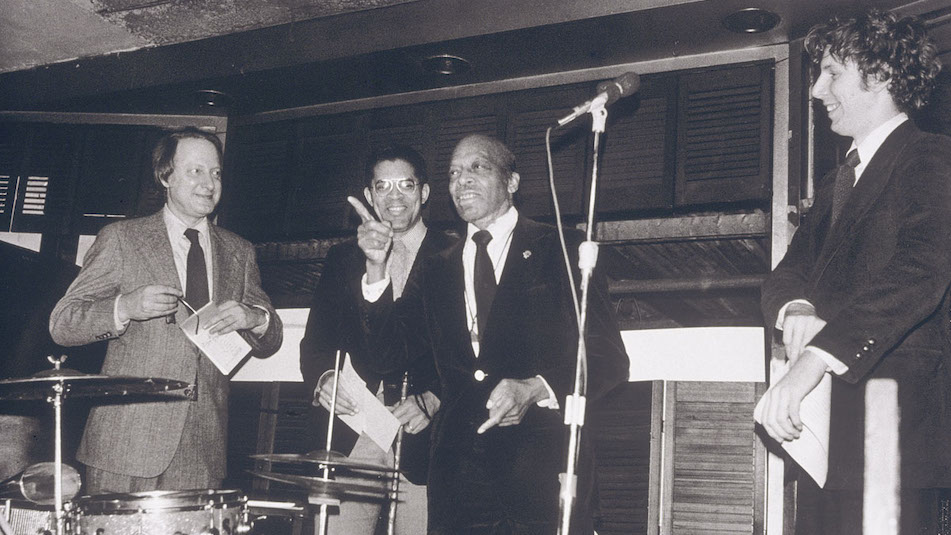

Papa Jo Jones receiving his certificate from the Jazz Oral History Project at the West End bar, January 1981.

(L–R): Dan Morgenstern, Ron Welburn, Papa Jo Jones, Phil Schaap.

Q: Let’s talk about Papa Jo Jones. You met him in August 1956, when you were five — you and your mom were backstage at the jazz festival on Randall’s Island. It was a random meeting. What were you even doing backstage?

A: You’d have to ask my mother! I don’t know how I got there. My father still had connections in the jazz industry. That’s probably the back story.

Q: Over the years, Jo became one of your good friends and probably your most important mentor. In a nutshell, what did he teach you?

A: He told me about jazz. He explained its prominence in the American experience both as an artistic and a sociological phenomenon. He’s the guy. And he’s a genius to boot. And a great drummer. I’m sitting there in awe. In 1956, there were a lot of people who could tell you about the Basie band. But this was Jo Jones. And there weren’t too many children showing up on his doorstep to get the lessons. So I guess I was appreciated because I was a member of such a small configuration.

Q: Not too many five-year-olds were familiar with Prince Robinson.

A: I guess that’s true.

Q: Jo schooled you over the years. You’d go to his apartment. He’d play records for you. He’d tell you stories about Basie and Lester Young and Herschel Evans, explaining their artistry to you.

A: He did all of that.

Eddie Durham

Q: And you became a proponent of the Basie band — which brings us back to your friend Eddie Durham. In 60 seconds or less, for people who don’t recognize his name, explain the importance of Eddie Durham.

A: He’s the most overlooked and important genius of 20th century music. He’s the father of the electric guitar. He taught Charlie Christian. He wrote the entire book for the original Basie band. He arranged “In the Mood” for Glenn Miller.

And he wrote some all-time blues numbers like “Good Morning Blues” and “Sent for You Yesterday (And Here You Come Today).” And he wrote “Topsy,” which was a hit for different people in different decades, starting in the ‘30s, but going into the ‘60s. It was a hit for Basie, and (drummer) Cozy Cole recorded it in the rock ‘n’ roll era with an anonymous Coleman Hawkins on tenor. It’s a 45 on the Love label.

Eddie’s also an excellent trombonist. He’s a definitive arranger of the Southwestern style. He was the most humble genius I’ve ever met — and, because he was so humble, maybe the most overlooked. But how many people are as important to 20th century music as Eddie Durham? Very few. The list would be in single digits.

Q: You recently sent me an essay you’d written about early jazz. I latched onto a turn of phrase at the end of the piece: You expressed hope that new listeners would start to explore the “wondrous sounds” of the music.

A: There is a wonderment to it. You’re exploring this new world of incredible fascination and potential joy. And they are certified wonderful things. Just because you never heard of Don Redman with McKinney’s Cottonpickers, it doesn’t mean it’s not wonderful.

Q: There’s a story about you singing a Lester Young solo — note for note — for your parents when you were little. What was the tune?

A: “Taxi War Dance.”

Q: How old were you when you first heard it?

A: We were still living in Astoria, so I had to be five or less. Because my mother would play it on a 78 record changer when she came home from work. (She was a librarian at a public library branch in Jamaica, Queens.) You remember the sway bar on the record changer? If you left it hanging out, it would just keep playing the same record over and over again. So she would just put down “Taxi War Dance” and it would play for an hour. That would be 20 plays. And one day, the record had been played so much that the needle just went through it and the shards flew all over the place, and that was the end of “Taxi War Dance.”

But after Prez died (in 1959), it came out on the Lester Young Memorial Album — and, of course, my parents had now converted to LP playback. So now I’m eight or nine years old. And they put on the album, and “Taxi War Dance” came on — and I sang the solo. And we hadn’t played the record in years, because the 78 had been gone.

My parents looked at me like I was a demon.

(Schaap starts singing Lester Young’s solo on “Taxi War Dance.”)

Pardon my singing! And now here’s the bridge. (He sings the next part of Young’s solo.)

Q: If you were going to recommend one Lester Young track for people to listen to, what would it be?

A: That’s a helluva reduction you’re asking for. (pause) Well, “Lady Be Good,” master take, Jones-Smith Inc., early Nov. 1936. That’s not my decision. That’s Jo Jones’s; I’m just endorsing his endorsement.

Lester Young: "Lady Be Good" (1936)

Q: And what about Charlie Parker? Name one essential track.

A: “Ko-Ko,” master take, Nov. 26, ’45.

Charlie Parker: "Ko-Ko" (1945)

Q: How about your friend Ornette Coleman?

A: Can I say two? “Peace” and “Lonely Woman.”

Ornette Coleman: "Peace" from The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959)

Ornette Coleman: "Lonely Woman" from The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959)

Q: Name a single essential jazz album for people who are getting into the music.

A: Miles Ahead with Gil Evans and Miles (Davis) isn’t a bad choice. It’s ridiculous to reduce it.

Q: Sorry. Name a single jazz track that people should listen to.

A: “West End Blues,” Louie Armstrong and the Hot Five.

Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five: "West End Blues" (1928)

Q: Why?

A: It’s arguably the most important moment in all of jazz improvisation. And if you want to work on a stretch, you could say that everything since has been derived from it. Louie’s fanfare at the top is one of those wondrous things we were talking about. You can count it as 12 bars if you want to. And you can count it as six bars. But the truth of the matter is, you can’t count it. It’s as abstract as anything that my good friend Ornette did. It’s just a different type of abstraction.

Q: Another quick question: What’s your favorite technology for listening to music?

A: I can simplify this, because I know you want short answers. Tubes beat transistors. Belt-driven turntables beat direct drive. Analog beats digital.

Q: Do you mostly listen to vinyl?

A: I pull out the best sound source of the music I wish to hear and try to play it back at its optimum. And that goes for digital. I ponied up some heavy bread; I have a very good CD player.

Q: I’ve got to get you to tell me a couple of your classic stories.

A: OK.

Q: Tell me about your eating contest with Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

A: Well, I’m growing up in Queens, and there’s this huge jazz community. And it’s a bedroom community, so getting together socially is a very big deal. And my parents threw numerous parties for the musicians, and it was wonderful. And when the weather would get nice in the spring and early summer, my mother and (clarinetist) Herb Hall’s wife — who, oddly enough, is named Annie Hall — would occasionally make these picnics in Cunningham Park. And that’s when Annie would bring out her mince pie specialty.

Anyway, Rahsaan would come out to Hollis, and it was very easy to become aware of how much Rahsaan liked food.

Rahsaan Roland Kirk

Q: How did you get to know Rahsaan?

A: Well, I’d befriended Sonny Brown, because he hung out with Jo Jones.

Q: Sonny Brown was Rahsaan’s drummer.

A: Right. And this led me into Rahsaan’s world. And Rahsaan — you think of him as Rahsaan. But he’s really into Don Byas and Sidney Bechet. And when he comes out to Hollis, he wants to hear Jelly Roll Morton Red Hot Peppers records, and he liked to talk to my father about Don Byas, because my father was friends with Don Byas. And Rahsaan came to realize that I was young and up-and-coming; I knew a pile of stuff. And Sonny Brown probably told him that Jo Jones was nurturing me.

So on this particular afternoon, this whole crowd from Rahsaan’s circle — they came to our house, to our dining room. There was no picnic; it must have rained that day. And I’m a growing boy — you know, teenagers, when they get the hungries, they can go to town. And I don’t remember whether Rahsaan challenged me or whether there was some coaxing from the musicians there. But we had an eating contest. And we whipped through some of my mother’s specialties, like beef bourguignon. And there was a thing called Hoppin’ John, which was sort of like a bean and vegetable quiche-slash-pie-slash-pan dish. And we were eating all of this, and I imagine we were already feeling full.

But, you know — competition! And that’s when Annie Hall brought out her mince pies and Rahsaan said to me, “Can you eat a whole one?” I said, “I think so.” And he said, “I think I can, too! Let’s see who wins!” And we each ate a mince pie — we each ate the whole thing. And then he declared a tie, and I agreed.

Q: Eating a whole mince pie sounds pretty gross, Phil.

A: I was 17, 18, going through a growth spurt! But he must’ve been in his 30s. At no point in my 20s or 30s would I have eaten a whole mince pie. I mean, what are you talking about? Like when I took Sun Ra out for ice cream, I’m not going to eat a quart of banana and strawberry.

Q: How often did you take Sun Ra out for ice cream?

A: Well, he came to the West End fairly regularly — and he liked ice cream.

Q: What was his favorite flavor?

A: Bananas and strawberry.

Q: OK, I’m not going to make you tell the Sun Ra-Steve Lacy story.

A: Why not? It was one of the most amazing and bizarre things. We had a band doing Django Reinhardt specialty music on a Sunday night at the West End; it was early in November or maybe December, 1981. And it’s the midnight set and we’re broadcasting live on WKCR. But there are only two people in the audience — and it’s Steve Lacy and Sun Ra.

And they loved it.

The problem was, Lacy was alone in the back of the room and Sun Ra was toward the front. And I said, “Steve, would you mind sitting with Sun Ra close to the bandstand, so there’s some positive reaction for the fellas to see?”

Q: I’ve got a picture of the West End in my head. Sun Ra was in a booth up front?

A: He was in the booth he always sat in, right up by the piano. If you remember the layout, on the left-hand side of the room — looking up toward the stage, stage right, there was a nice booth that backed up to the piano. And Sun Ra sat there and I got Steve Lacy to go there and sit with him. It was great. You know, we had good music at the West End.

Q: Did you, Steve, and Sun Ra give the band an ovation at the end of the set?

A: We did. And if I remember correctly, Sun Ra had some kind of strange whistle that he pulled out and blew. They loved it, and they talked to the musicians after the broadcast.

That’s a real jazz story — there was no one there.

Former location of the West End bar, 2911 Broadway, NYC

Q: OK, here’s another reductionist question for you: If you could re-live one night in a club — any club, from your entire life of going to clubs — what would it be?

A: Well, I like the night at the West End when Roy Eldridge said, “Do we have to stop playing?”

And I said, “Of course not.” And the result was an after-hours jam session. Roy commandeered the stage. The musicians stayed, and there were a lot of people sitting in.

Q: What was the year and who was in the band?

A: Late ‘70s, and definitely a Sunday. Buddy Tate on saxophone. Dill Jones on piano. I don’t remember all the sit-ins. I think (saxophonist Harold) Ashby was there. Big Nick Nicholas. I’m tempted to say the drummer was Ronnie Cole. And before too long it got to be 4 a.m. — you know, the bar’s got to close at 4 a.m. in New York. So this is the only time this happened at the West End. I went to the microphone and I said to the audience, “You don’t have to leave. And if you stay, everything’s on the house. But if you stay, you can’t leave until 6 a.m. when we open for the breakfast trade.” And almost everybody stayed.

Q: Describe the music.

A: Roy Eldridge was in charge of a jam session — what else is there to say? They played blues, a lot of blues. Slow, fast, with singing, without singing.

But there’s another part to the story. There was a trombone player — he lives in Germany now — named Jerry Tilitz. And he liked to call me on Sunday nights after the musicians had gone home and shoot the breeze. So the phone rings in the office, and it’s Jerry, who hears the music and says, “What record are you playing?” And I told him, “That’s not a record, man. Roy Eldridge is turning this into an after-hours jam session.”

And he said, “I’m coming!”

Now, he was out in Brooklyn. He was going to catch the No. 2 train and ride it to 96th Street and switch to the No. 1. You know, this is 4:15 in the morning on a late Sunday night.

Anyway, he arrives — and the doors are locked tight. But you may remember there was a fire door behind the stage at the West End. So he’s out on the street. He took his trombone out of the case — I’m thinking he must’ve tapped on the window behind the stage. So I walked through the musicians while they were playing on stage — while Roy’s singing. He’s singing a blues. And I let Tilitz in through the fire door. And Jerry comes in with his trombone operational, and starts playing an obbligato behind Roy singing. And you know, Roy was tasting; the bar was open. It was all free. He knows there’s no trombone player. But he hears a trombone player behind him, playing in his ear — playing in his tempo, obbligato to his blues singing. And he looks really perplexed. And then somebody else starts soloing, like Buddy Tate. So Roy turns around; he sees Tilitz. He says, “How did you get here? You drop from outer space?”

But I’d let him in through the fire door!

Q: So what happened at 6 a.m.?

A: That’s when Julio came in; I don’t remember Julio’s last name. I can tell you he was born July 6, 1931. He comes in. He’s the day cook. And sport that he was, he made breakfast for everybody. And I mean the audience, the musicians, and the staff. We all had breakfast together, around 6:30, quarter to 7 in the morning. And then everybody went their separate ways.

Q: The West End comes up again and again in our conversations. Why are you so proud of what you did there through the years? (Schaap booked music there from 1973-92.)

A: Well, I took care of the people who took care of me. And it was a great scene. And it ushered your generation into a wonderful music.

Q: It was across the street — across Broadway — from Columbia’s Ferris Booth Hall, where WKCR was on the second floor. Over the past 51 years of doing shows on KCR, is there a single radio moment that stands out for you?

A: The one that I still linger on — and there must be 50,000 of these suckers — is the interview with Lester Young’s brother Lee, on Lester’s birthday on August 27, 1988. He opened up and we just stayed on talking about Lester Young for over three hours. That was a very amazing moment.

Q: Who was the first person you interviewed on WKCR?

A: The first person interviewed was me. Because of my expertise in this so-called pre-jazz, I would be brought in when someone said, “We need to do a show on Buster Smith. Who is he?” And I would be the guest, and I would bring the Buster Smith album on Atlantic and the records he made with Eddie Durham. And I guess I would talk a lot; there would be a whole show on Buster Smith!

Q: And when you got your own show, who did you interview first?

A: The Basie guys first. Doc Cheatham. Earl Warren and Benny Morton and Buck Clayton. I did a very long show with Buck Clayton in which we debated. Buck (who played trumpet with Basie) said he thought the Basie band in the ‘40s — ’41, ’42, ’43, until he got drafted — was much better than the Basie band in the ‘30s. And I argued with him — politely, of course, because he’s my guy. But he felt strongly about that.

So then I brought in Earl Warren (who had been Basie’s lead alto saxophonist) to do a follow-up show, and I was shocked. Earl said, “I agree with him. And I’ll give you one of the reasons: We had a little more money. We bought better instruments.” He said, “Our intonation got a whole lot better. We played cleaner on better instruments.” So there I was — 19, 20 years old — arguing with Buck Clayton and Earl Warren. And I’m still going through it in my mind to this day. Because I’m more of a 1930s, Eddie Durham-Basie band guy.

Q: People may not know that KCR’s antennae used to be atop the World Trade Center — and that after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, the station had a serious period of decline. It had very little money. It had a crummy transmitter and minimal listenership.

But you raised $750,000 for the station, largely by writing a book about Billie Holiday as a way of soliciting donations.

A: It saved the station. Amiri Baraka and Peter Jennings were among the people who donated. If you look in the back of the book, there’s page after page of names — all the people who donated. In total, 978 people ponied up big bread to save KCR. Two of Sidney Bechet’s grand-nieces donated. So did Lee Konitz and Jimmy Heath. How’s that for diversity? It’s probably the thing I’m most proud of.

Phil Schaap interviews Sun Ra on WKCR in April, 1987

Q: After all these years, how big is your personal archive of interviews?

A: Funny you ask; my students just counted them. It’s a little bit over 2100 — and that’s just the interviews. I’ve got about 6000 78s and 10,000 LPS. And then I have my own tapes with all kinds of music.

Q: We met at WKCR in 1972. If you were going to explain to people what was so exciting about the station in those early days, what would you tell them? What was our mission?

A: It was about nurturing culture that was in commercial decline. We made a decision to help worthy art — jazz — that was being totally abandoned by regular broadcasting. And that was a most remarkable development coming out of the whole student rebellion of the late ‘60s, which was somewhat centered at Columbia.

We took Columbia’s boring radio station and made it a vital community service. Nobody was going to play Charlie Parker — or Louie! Nobody did it like we did! And sometimes nobody plain did it. They had already abandoned it, and we put it in the foreground.

I remember being at the station on September 17, 1970; that’s the day we decided KCR was going to be the jazz alternative. And it was the day before Jimi Hendrix died. And I remember somebody said, “Jimi Hendrix doesn’t need KCR.” Albert Ayler, who was still alive, did.

Q: Back in the early '70s, I didn’t know that you’d met Sun Ra in the 1960s and that you were friends with Ornette Coleman — you even helped build the stage at his loft, Artists House, down on Prince Street. I don’t think anybody at WKCR knew those things. Do you feel that you get pegged or misunderstood as a traditionalist — that people think you don’t know the full range of the music?

A: I do, but it doesn’t matter. The art matters. I don’t matter. For instance, it was fine with me that I got pigeon-holed; it served a purpose for all you guys at the station. You guys couldn’t take care of Eddie Durham, so you got me to do it. You didn’t need me to take care of Ornette. I remember subbing on a Monday on “Jazz Alternatives” and playing all Dolphy. Someone said to me, “What are you doing? I didn’t know you knew these records?” And I said, “Well, you know, I like Eric Dolphy. I heard him play live. I spoke with him a few times. He’s great. What’s the problem?”

And today, I probably could teach a hard bop class at Juilliard as well as anybody. But you don’t need me to teach the Clifford Brown-Max Roach Quintet. So I’ve come full circle, in that I’ve been pigeon-holed back into this earlier specialty. And the courses I teach are somewhat foolishly named: “The Origins of Jazz.” “Roots of Jazz” is another one. I’m teaching Louie Armstrong, for heaven’s sake, and Duke Ellington. What do you mean, “origins of jazz”? If Duke and Louie aren’t jazz, then we’re done for, anyway.

But you know, Bird’s in trouble, too. Beethoven’s in trouble.

Q: The diminishing audience — it was always a problem.

A: That is the problem. There’s no audience. The schools can create 2000 more hard bop musicians under 25, but at the same time we’re losing 2500 people who want to hear hard bop music. We’re diminishing the fan base while increasing the number of people looking for work. It’s insane. And it’s going to take a couple of generations to fix this mess — and that’s if we do everything right.

My whole life has really been about jazz education. I’ve been training musicians my whole life, but I can’t find ‘em gigs anymore — not unless we have audience development. So you have to create understanding. You hope that love comes forward, but you can’t create that. You can’t make anybody love the music. But you can give them an understanding, and you can give them access. That’s one of the things KCR did — look at the music we gave to the New York City audience.

Q: What’s the most joyful part of this whole lifelong pursuit of yours?

A: The music itself. I’m still incredibly thrilled by listening.

Q: Last question: What does getting this NEA Jazz Master award mean to you?

A: Well, Sonny Rollins said it: “It’s an honor to be honored.”

The federal government is helping musicians. You know, that’s what I did at the West End.

The NEA is helping the people who make the music — the musicians. And they’re helping scholars, too; they’re endorsing scholarship. And at this late stage — I’m old and sick — they’re putting a credential on what I’ve done. And maybe it’ll even open some doors.

So, I’m thankful. Remember, I was involved long ago with the National Endowment for the Arts — their Jazz Oral History Project. I was assistant director. It’s one of the few paying jobs I’ve ever had in jazz! We did 162 full life-story oral histories. And one of them was Andy Kirk (swing era saxophonist and bandleader). I lived at Andy Kirk’s apartment in the famous 555 — this palatial apartment building at the top of the hill in Sugar Hill on Edgecombe Avenue (in Harlem). And Andy Kirk — you know his memoirs were eventually published, and so was the oral history. So there you go: the Jazz Oral History Project — that was rooted in the NEA. Hallelujah!

So I’ve come full circle with them. You know, I became assistant director there at the end of the ‘70s. And here it is, 2021, and I’m going to be feted on April 22nd — which, just to tie it into a family thing, is my mother’s birthday. She would be turning 105. It’s Mingus’s birthday, too, man — another holiday! And I knew them both. Yes, I knew my mother! But by God, I also knew Charles Mingus, and I was a little scared of him. And when he called the station, you guys always handed the phone to me. But I was quakin’. My knees were shivering, because he always had something forceful to say and a demand to be made, and by God, we met his demand. He liked us.

Watch the 2021 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert online Thursday, April 22, 2021 at 5 PM PT (8 PM ET) from arts.gov and sfjazz.org. This is a free event.

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.