Beyond Genre: Taylor McFerrin Creates His Own Musical World

August 21, 2018 | by Richard Scheinin

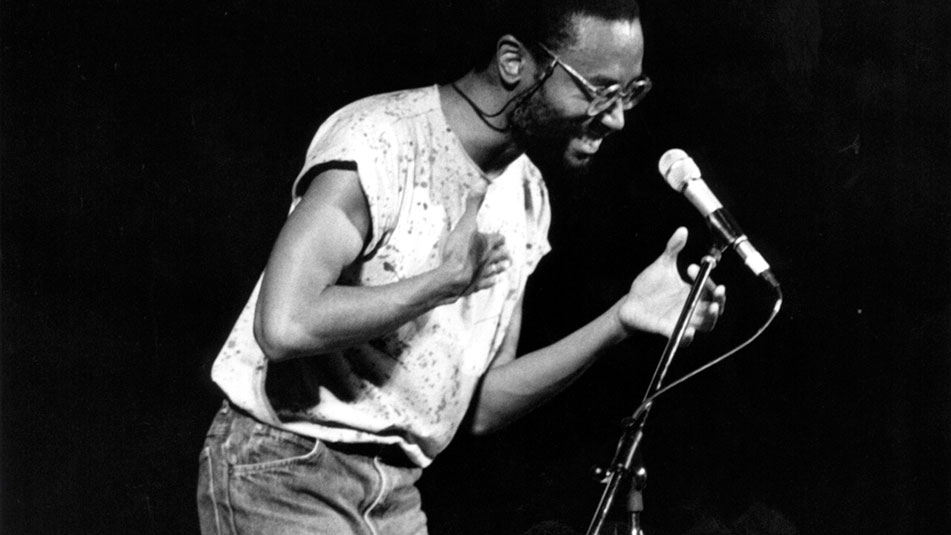

Taylor McFerrin at SFJAZZ, 2017 (Photo courtesy of Che Holts)

Taylor McFerrin doesn’t need a band.

He never did. When he was in high school, he would shut himself in his bedroom and go to work, obsessed with sampling and making beats, intent on becoming a hip-hop producer. “And what’s funny is, I think I chose to be a beat maker because it felt like my own thing,” he says. “It was my way of doing music, trying not to do what my dad does” – his father being Bobby McFerrin, the singer and multiple Grammy winner whose allegiances often lay with the jazz world. “While for me,” Taylor says, “it was always hip-hop, which wasn’t really his thing.”

Twenty years later, Taylor McFerrin (who performs Sept. 6-9 at SFJAZZ) is deep into his own thing as a keyboardist, DJ, beat-boxer, composer and producer. At age 37, he might seem to have little in common with his father’s musical world; in fact, their careers have been shaped by a set of shared perspectives. For one thing, Bobby McFerrin has never needed a band; he made his name as a solo performer, turning himself – his voice, his body – into a one-man choir and percussion section. The message was this: You are your own musical world; explore it.

Taylor McFerrin has done exactly that during years of touring as a solo artist, playing late-night clubs in Rio de Janeiro, Dublin and New York, refining his sound. Based in Los Angeles, he is a gear-head and “synth nerd” – he collects analog synthesizers from the ‘70s – who designs instant soundscapes that mushroom from trance to groove. Like his father, he is an improviser. Like his father – who gets defined as a jazz musician, but who also has conducted symphony orchestras – he disavows genres, moving across jazz, hip-hop and electronica circles. But again like his father, his jazz credentials are plentiful: He is a member of R+R=Now, keyboardist Robert Glasper’s new all-star band, and his most constant collaborator is the great jazz drummer Marcus Gilmore, who will join him for allfour nights at SFJAZZ’s Joe Henderson Lab.

In the end, there are a lot of parallels in the ways my dad and I approach music,” Taylor says. “We’re just arriving from different angles.

Five years into their duo collaboration, he and Gilmore will introduce new compositions at the San Francisco shows: “We’re both wrapping up solo albums,” McFerrin says, “so we’ll try out the material – but attacking the songs differently each night. I grew up in San Francisco. A lot of my family and friends are there, and when I go back, I base the show on not wanting them to come and see me do the same thing I did last year.”

That’s not likely.

When he plays solo, McFerrin may start with swirling textures or trigger one of the gazillion beats that he’s designed at his home studio. “Then maybe I’ll play a keyboard part, say, something on the Fender Rhodes,” he says. “I can play it as long as I want, then press a button and it lets me loop up the chords. Press another button and it keeps the loop going. Then I may add drum sounds and build another beat from scratch, adding a bass line and other elements. So coming to my show is sort of like coming to my studio to see how I come up with ideas, but in a super-accelerated form. I’m not really concerned about being perfect as much as finding a really cool vibe and running with it.”

When he plays with Gilmore, the choices multiply: “With Marcus, there’s this whole other world I’m able to enter where maybe I start building an idea one way, but he takes it off somewhere else entirely. Marcus pushes me. He pushes my musicianship a lot because he tours with Chick Corea and all the top players in the world, and I am not on that level in terms of technical chops,” McFerrin admits. “But because I’m a producer, I think one of my skills is bringing interesting sounds to the show – I always have a unique texture to what I’m doing. And because I came up making beats on beat machines, I can kind of save us from getting too nerdy. In a weird way, my technical constraints can help us connect to an audience that’s used to listening to all kinds of beats on the radio. So I put limits on Marcus that yield cool results, while at the same time he’s pushing me out of the box. There’s this gray area between us, and I think that gray area is where something unique happens.”

Marcus Gilmore & Taylor McFerrin at SFJAZZ (Photo courtesy of Che Holts)

You can watch it happen all over YouTube.

For instance, there is a 2015 performance at a jazz festival in Vienna where McFerrin begins with some of his beloved ‘70s synth sounds – riffs reminiscent of Roy Ayers or Stevie Wonder. Gilmore stares at the floor for a minute, soaking up the mood, then shimmers up his cymbals and launches into a draggy hip-hop beat that gradually morphs toward a jazz feel. McFerrin feeds him more riffs and finally drops out, leaving Gilmore to an extended solo. It’s tumultuous, and when he hints at a blues shuffle, McFerrin instantly jumps on it with his keyboard. A minute later, McFerrin riffs a bit on “You’ve Got It Bad Girl” while Gilmore keeps building his crazy solo. Then as they flow back into their duet, both musicians’ heads are bobbing; the music is intense, physical, and McFerrin’s keyboards are super-rhythmic. It’s almost as if a couple of drummers are going head-to-head as they wind down their eight minutes of ‘70s jazz fusion, hip-hop and cosmic soul.

McFerrin and Gilmore at 2015 JazzFest Vienna

That fluid mixture of genres – hard to define – encapsulates what many young jazz players are doing right now. Think about Glasper or Thundercat, the bassist, or Flying Lotus, the producer – or McFerrin, who plays with all of them.

Listen to Taylor McFerrin's curated "Behind The Sound" playlist.

When he was growing up in San Francisco, his family “was always listening to the same records,” he says, sorting out his early influences. “It was always James Brown, the Beatles, Stevie Wonder. And then my dad was always listening to the Yellow Jackets and Joni Mitchell. And my mom’s a music lover, and we used to throw a lot of parties. It was always funk and soul music, good party stuff.”

McFerrin took piano lessons in grade school: “But I stopped probably when I was 10 – and then I forgot how to play everything!” The family moved to Minneapolis when he was 13, and over the next few years, as he got into hip-hop, he was “introduced to beat machines and electronic gear and once I got more and more interested – this was a few years later – I started collecting the instruments used on all those classic, ‘70s jazz fusion records.” He was drawn to the music of that era – by the political statements, the embrace of Black consciousness and the warmth of the instrumental sounds. “Those instruments just have an alive feeling to them. All the old synthesizers have these knobs where you start turning things and you create a sound you weren’t even expecting. So the musicians of that era were creating sounds that had never been heard before -- and that represented their personalities. I can tell when it’s Herbie (Hancock) versus George Duke, not just because of their playing styles, but because of how they’re manipulating the electronics, how they’re turning those knobs.”

With time, he also discovered that his favorite hip-hop producers were sampling his ‘70s jazz heroes. For McFerrin, there was a lot going on when he shut his door and went to work, both as a listener and as a fledgling musician: “It was a very self-taught, me-in-my-room-trying-to-figure-things-out process. Every once in a while I would pick up some books about theory and kind of realize what I was trying to wrap my head around. I’ve always been getting better and better over the years and just gaining more knowledge, but I never went to music school.”

After graduating high school in Minneapolis in 1999, he attended Boston University for a year. Then he moved to New York, enrolling in a liberal arts program at the New School, where he became friends with some of the kids in the jazz program. He also took a sales job at the Sam Ash music store on 48th Street in Manhattan – an important move, because this is where he started to get good at playing beats and drum parts with keyboards. Since “most musicians don’t wake up until noon,” the morning hours were quiet at the store. He and a few of the other employees passed the time by jamming on keyboards: “That was everybody’s favorite part of the day,” says McFerrin, who credits those jams with giving his keyboard drumming a “live, human feel.”

Living in Brooklyn for 15 years, he developed his solo career and eventually landed a recording contract with Flying Lotus’s LA-based Brainfeeder record label. In 2014, it released his first full album, “Early Riser,” which features appearances by an eclectic group of guests: Glasper and Thundercat, soul singer Emily King, Brazilian jazz pianist César Camargo Mariano – and Bobby McFerrin.

Like father, like son. Bobby McFerrin (above) performing at the 1984 "Jazz In The City" Festival presented by SFJAZZ; Taylor McFerrin (below) at the SFJAZZ Center in 2017 - Bobby was in attendance!

Taylor moved to Los Angeles three years ago to take advantage of the “super-strong energy” of its beat scene and to work more closely with Flying Lotus and other producers. His circle keeps expanding: Glasper’s R+R=Now band (“R+R” stands for “Reflect and Respond”) also includes saxophonist Terrace Martin, trumpeter Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah and bassist Derrick Hodge. They all float between the jazz and hip-hop scenes – and like McFerrin, they all grew up listening to hip-hop and its sampling of ‘70s jazz. “That’s been a major connecting point for the band,” he says. “We all feel that we’re a part of that intersection.”

How does he feel about hanging with seasoned jazz players?

“The barrier for me is when I’m playing with cats and they want to play a standard that I don’t know,” says McFerrin, who is nothing if not honest. “I’m not fluent enough in the language where they just call out the tune and they know the changes, and it’s just `go.’ I can play well enough in the studio environment, but I can’t really do it on command in any key at any tempo.

"But I’m fine with that,” he adds, “because a lot of the cats that I know that are killing it – they can’t really make a track at home that sounds super unique and has a different take. So, yes, I’m trying to improve my chops with every year, but I’ve also learned to accept my constraints. I think it was definitely valuable for me to try and figure out a lot of things on my own. It allowed me to find a sound and an approach. It’s what defines me as a musician – my sound."

A staff writer at SFJAZZ, Richard Scheinin is a lifelong journalist. He was the San Jose Mercury News' classical music and jazz critic for more than a decade and has profiled scores of public figures, from Ike Turner to Tony La Russa and the Dalai Lama.